When David Haig finished college in Australia with a degree in biology, he found a job in a New South Wales government office rubber-stamping documents to record mortgage tax payments and property transfers. His tour in the bureaucracy lasted two years. “I decided there was more to life than rubber stamps,” he says, reminiscing in his office at Harvard University’s Botanical Museum. Haig returned to his biology studies at Macquarie University in Sydney, earning his doctorate in 1989.

While he was there, he became absorbed in the study of an unsolved problem in evolutionary biology. Researchers were learning that the process of conceiving a child is not nearly the tender, rhapsodic intertwining of the mother’s and father’s genes that one might imagine. Instead, it’s the start of a survival-of-the-fittest struggle that begins inside a fertilized egg and continues throughout pregnancy.

Natural selection usually had been thought of as a competition among species in the wild. Now it appeared that natural selection was operating within each fertilized human egg, as each parent’s DNA competed for control of the developing offspring, each with a different evolutionary goal.

Haig’s dreary rubber-stamp work oddly foreshadowed his biological studies. The fetal genes locked in this battle for survival, researchers had discovered, were “stamped,” or imprinted, with molecules that marked them as coming from either the mother or the father.

Only about 100 of the tens of thousands of genes that make up the human genome are marked with these gender-specific stamps, subsequent studies showed. But even though they are uncommon, they are critical for survival. If the imprinting process goes awry during gestation, it can lead to serious illness, or even death, of the fetus or the mother.

Haig wanted to know more: Why do these genes engage in this conflict? Wouldn’t mothers’ and fathers’ genes do better to cooperate with each other, increasing the likelihood that parents will have a healthy child?

Figuring Out What's Essential

The imprinting story begins in the late 1970s with Azim Surani, a young developmental biologist working in the University of Cambridge laboratory of physiologist Robert Edwards, acclaimed for his recent work in perfecting in vitro fertilization.

Surani was interested in parthenogenesis, a phenomenon in which healthy offspring are produced from an unfertilized egg and therefore contain only a mother’s genes. Parthenogenesis was known to occur in some fish, reptiles and other vertebrates (as well as in some invertebrates). But there were no known cases of it occurring in mammals. Surani wanted to test whether mammalian parthenogenesis was possible by trying to create a “virgin birth” in laboratory mice.

Normally an egg and sperm each contribute one copy of the full set of human genes to an embryo. (The lone exception, of course, is in the case of the sex chromosomes: Males carry one X and one Y chromosome, and females carry two X chromosomes.) Combining two copies of a mother’s genes would theoretically achieve the same thing, yielding an embryo carrying a complete complement of human genes. Everything that was known about genetics at the time suggested that such an egg, even though it carried no male genes, would develop normally. “We couldn’t think of a good reason why it shouldn’t work,” says Surani.

He tried fertilizing a mouse egg by injecting genetic material from another female mouse, but it didn’t work: None of the mice without any male genes developed to term. Some grew more slowly and were smaller than normal embryos; others had abnormally large yolk sacs. One had poorly organized brain tissue. Another had a beating heart, but no head.

Surani tried the experiment the other way, too, producing fertilized eggs with two sets of genes from a male mouse. Those embryos didn’t make it, either. He knew his experimental technique was correct because when he used the same method to combine male and female genes, the resulting embryos survived. The only possible conclusion, he believed, was that mothers and fathers each contributed something essential to their offspring. Whatever it was, Surani knew, it was not in the genetic sequence itself. A maternal gene that codes for, say, hemoglobin has the same genetic sequence as a paternal hemoglobin gene. He speculated something must be altering the seemingly identical mom and dad genomes, imprinting them with some kind of biological marker indicating their origin.

When he described his results to colleagues in the department of genetics, “they were very skeptical,” Surani remembers. His findings didn’t make sense.

But similar experiments conducted by biologist Davor Solter at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia bolstered Surani’s results, independently showing the same strange inability to create a mouse from two female genomes. But neither Surani nor Solter could explain why, in the larger scheme of reproduction, imprinting occurred. That’s where David Haig took up the challenge.

Fetal Competition

To get to Haig’s office in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, visitors snake through museum exhibits and past the gift shop. The office is nearly big enough for a half-court basketball game. Books line the walls and sit stacked on half a dozen tables. The office is empty of laboratory equipment; since Haig is a theoretical evolutionary biologist, his role isn’t to conduct experiments but to explain the results of others’ lab work. (His undergraduate laboratory experience, he says, involved counting “a quarter of a million bristles on fly bellies” — enough to drive him away from the bench for good.)

After leaving the lab behind, Haig focused his theorizing on evolutionary conflict within the womb. The notion of such a struggle was first suggested by his close friend Robert Trivers, a theoretical biologist at Rutgers who had observed an indirect form of sibling rivalry in which offspring each try to get more resources than their parents can allocate to them. (One example of such in utero competition occurs when fetal cells invade the walls of maternal arteries serving the placenta, making them expand and thereby bring more nutrients to the fetus. The mother is powerless to resist.)

Haig suspected that competing for resources also could give rise to a related kind of in utero conflict, between maternal and paternal genes. According to this idea, called kinship theory, males and females have a strong interest in seeing their offspring survive, but their reproductive strategies differ, leading them to want different things for their offspring.

In all but a few mammal species, females will have multiple partners. So it’s in a male partner’s interest for her to devote all possible resources to developing his embryos.

Females, on the other hand, have evolved to maximize the number of surviving offspring, each of which might have a different father’s genes competing for her resources. Her strategy is to give an embryo only what it needs, conserving her resources for current and subsequent offspring.

The stage was now set for competition, Haig believed. And the machinery enabling that competition, he theorized, consisted of the imprints stamped on each fetus’s genes. By turning genes on or off, these molecular imprints could change how the body reads the genetic code.

Although he didn’t yet know how imprinting worked, he knew there must be two main categories of imprinted genes: those that are expressed, or “turned on,” only if inherited from a father, and those that are turned on only if inherited from a mother. Haig theorized that in keeping with the father’s reproductive strategy, genes inherited from fathers would encourage more growth, spurring the fetus to demand more resources from its mother while it’s in the womb. Genes inherited from mothers, on the other hand, would slow that growth, enabling the mother to conserve resources for her subsequent offspring.

That was the theory. But how did it mesh with what was known about imprinting from experiments?

Illustration: Jay Smith, DNA Bands: The Biochemist Artist/Shutterstock

Tug-of-War

Surani had first identified the phenomenon of imprinting, but he wasn’t sure which genes were involved. It was Elizabeth Robertson, then at Columbia University and now at the University of Oxford, who was the first to identify an imprinted gene. She was investigating the roles that various genes play in the normal growth and development of mice by deactivating, or knocking out, specific genes in living animals. She then observed how that would affect developing embryos.

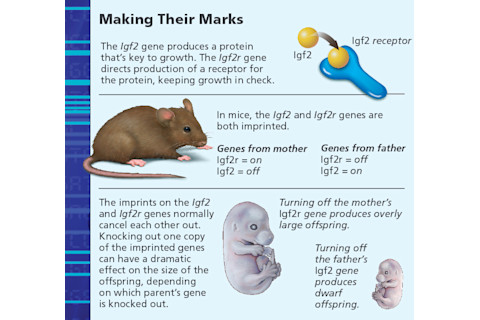

In 1991, Robertson and her colleagues reported an unusual discovery involving a gene called Igf2, which is responsible for producing a protein known as insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-2), important for the growth of many kinds of tissue in the developing fetus. When Robertson knocked out the Igf2 gene in mouse mothers, nothing happened; the offspring were normal. But when she knocked it out in mouse fathers, the embryos grew to only about 60 percent of normal size. Clearly, when the gene came from a father — and only then — it was essential for growth.

Robertson’s findings fit nicely with Haig’s theory: The paternal Igf2 gene encouraged growth of the offspring, so it would make more demands upon its mother. This was critical evidence of the competition between maternal and paternal genes. Other researchers soon discovered that other genes were similarly involved in this paternal-maternal conflict — and that paternal genes pushed for growth, as Haig theorized.

The father’s strategy carries a risk: It can weaken the mother and leave her too depleted to have more offspring.

But that’s no concern of his. Next time around, he will mate with someone else. Still, taken to an extreme, the father’s tactics could kill the mother, and the fetus would not survive. That usually does not happen, however, because evolution has supplied mothers with a powerful countermeasure — an imprinted gene of their own that can keep IGF-2 in check. The gene, Igf2r, directs the body’s cells to produce IGF-2 receptors that stick to the protein and prevent it from circulating and promoting growth.

In 1991, biologist Denise Barlow and colleagues at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna discovered that like Igf2, Igf2r was also imprinted, but with the opposite effect: The receptor was active only when it came from the mother. When the Igf2r gene is knocked out in mothers, the offspring grow too big and die before birth. When the gene is knocked out in fathers, nothing happens.

Humans have counterparts to the genes Robertson and others have probed in mice. And in humans, too, when the imprinting process goes awry (as when a gene that is usually turned on is switched off, or the reverse), the consequences can be devastating. When the mother’s and father’s copies of the Igf2 gene are both mistakenly turned on, for example, the fetus gets a double dose of growth factor. In humans, this abnormal pattern of imprinting causes Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, a condition in which children are born weighing more than 50 percent above normal and have a host of other abnormalities.

The opposite mistake can also occur. If the father’s Igf2 gene is mistakenly silenced, the fetus doesn’t draw on its mother’s resources the way it should, and it is born below normal weight.

“It’s a tug-of-war,” Haig says. “You’ve got these two sides tugging on the rope. They’re not shifting much — it’s just a little bit one way or the other. And they come to depend on each other, on the other side holding the rope. If you get a mutation in an imprinted gene, you get a really pathological outcome. One side has let go of the rope.”

Imprinting on the Brain

Among the approximately 100 imprinted genes discovered so far, about half of them, including Igf2, make proteins in the brain, raising the question of whether imprinting errors in genes that control the structure and function of the brain might contribute to mental illness.

The answer could be yes, says Bernard Crespi, a geneticist and evolutionary biologist at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. But that can be a difficult connection to prove. “It’s bringing together two very different areas that had never been connected before: evolutionary and social behavior theory connecting up with psychiatry. It’s been a challenge making inroads into the psychiatric literature,” Crespi says.

Still, he and a colleague, sociologist Christopher Badcock, formerly at the London School of Economics, believe the evidence is mounting. They contend that upsets in the tug-of-war between imprinted genes in the brain could help explain the origins of some mental illnesses, including autism and schizophrenia. Some known imprinting disorders already have been linked to mental illness, including Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. In addition to suffering growth abnormalities, patients with this disorder also have abnormally large brains and an increased risk of autism.

Could the opposite hold true? Could a fetus that lacks IGF-2 and is smaller than normal develop a pattern of brain abnormalities that produce, essentially, the opposite of autism?

Crespi and Badcock believe so. They contend that mental illness can be thought of as occupying a spectrum, with autism at one end and schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression at the other. People with autism often have difficulty understanding and appreciating what others are thinking. Now imagine people with the opposite problem: a highly developed ability to tune in to their social milieu — even to perceive things that are not happening. Such people, Crespi and Badcock suggest, might hear voices that aren’t there, a symptom of schizophrenia.

Recent findings fit Crespi’s predictions. Researchers in Hong Kong have found reduced activity in the Igf2 gene in people with schizophrenia. Reduced expression of paternal genes (Igf2 is active only when it comes from fathers) should tip a person toward the schizophrenia-depression end of the mental illness spectrum, according to Crespi.

Even clearer evidence that disruptions in gene imprinting can undermine mental health comes from studies of Prader-Willi syndrome, a disorder that affects growth, sexual development and cognitive ability. Loss of paternally expressed genes leads to psychosis in at least half of these patients.

For Haig, such findings raise deep philosophical questions about the nature of a human individual. The traditional view, he says, was that an individual was “something that cannot be divided.” But the existence of imprinting and its influence on how the brain and body develop underscore that at a fundamental level, the individual is divided. The body is not a machine, a collection of cogs working toward one goal, he concludes. We’re each organized “more like a social entity, with internal politics and agents with competing agendas.”

The evidence of such internal turmoil is all around us. We hesitate over decisions. We decide whether to cooperate or compete. We waver between immediate gratification and long-term planning. Perhaps the push and pull within each human being is the settling of scores among our competing genes.