On Westwood Boulevard in Los Angeles, just off the University of California campus, the street is jammed at lunchtime. The tones of all humanity flow past, faces from Santa Monica, Singapore, and Senegal, a stroboscopic stream of light and dark.

Notwithstanding such contrasts in appearance, comparisons of our DNA show that human populations are continuous, one blending into the next, like the spectrum of our skin coloring. We all carry the same genes for skin color, but our genes responded differently to changes in solar intensity as bands of Homo sapiens migrated away from the unrelenting sun of the equator.

Still, it seems to be human nature to assign types to our fellow humans and then make judgments based on those types. Take this tall woman coming along the sidewalk and entering an Italian restaurant. Blond, but not California blond. In her early fifties, wearing a stylish suit and elegant shoes — a European. Physically she belongs to what one observer has called “the fair-skinned, fair-haired, gray-to-blue-eyed, long-limbed, relatively narrow-faced individuals that constitute a substantial portion of the population of Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, western Finland.” That is, the Nordic type.

Leena Peltonen is one of the world’s leading medical geneticists. In 1998 she was recruited from Helsinki University to become the founding chairwoman of the Department of Human Genetics at UCLA’s medical school. Trained as both a physician and a molecular biologist, she has discovered the genetic sources for many rare diseases, such as Marfan syndrome, a connective-tissue disorder. She has also found hereditary links to more prevalent conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, osteoarthritis, and migraine.

The raw material for her investigations is DNA collected from people in Finland. Research by Peltonen and by her compatriots Juha Kere, Jukka Salonen, Albert de la Chapelle, and Jaakko Tuomilehto have made Finland into a sort of DNA laboratory for mankind. Now its scientists are detecting the heritable imprints of heart disease, diabetes, and asthma. The country’s contributions to medicine and genetics are far out of proportion to its size and population of 5 million.

As research subjects the Finns are an agreeable lot. When asked to participate in studies, Peltonen noted, three out of four will say yes. Access to clinical records is much easier in Finland than in the United States because the health care system is streamlined, centralized, and computerized. Foreign collaborators may tap into the resource as well. The U.S. National Institutes of Health has helped fund a dozen biomedical projects in Finland in the last decade.

But even more important for a geneticist, “the genealogies are already built,” said Peltonen, referring to the family pedigrees through which diseases can be tracked. “The setting of a limited number of ancestors and hundreds of years of isolation make Finns good study subjects.”

The genetic homogeneity, or sameness, of the Finns makes them easier to study than Californians, say, who hail from all over. To illustrate, Peltonen drew two pairs of human chromosomes, which were shaped something like swallowtail butterflies. Symbolizing two Finnish people, the four chromosomes were similar — banded horizontally with the same light-and-dark patterns. “These guys are the boring Finns,” she said with a trace of irony.

She drew another set of chromosomes representing a pair of Californians, and the banding patterns were quite dissimilar. The variance shows up better at the group level. Think of the human genome as a very large deck of cards, each card bearing a gene variant. The number of cards in the Finnish deck is fewer than the number of cards in the California deck because the Finns have fewer gene variants, or alleles, to play with. When scientists look for variants that cause diseases, they’re easier to spot in the Finnish deck because so many cards are similar.

The uniformity of Finns, created by several centuries of isolation and intermarriage, results in a large set of hereditary disorders. So far researchers have identified 39 such genetic diseases, many of them fatal, that crop up in the unlucky children of unwary carriers. Peltonen, who began her career as a pediatrician, said: “Genetic diseases transform the family. You know the children won’t get better.” Since switching her focus to research, Peltonen and her associates have identified 18 of the 39 endemic conditions.

Although far less common than cardiovascular ailments and much less of a drain on the health-care system, the hereditary disorders identified so far are so well known to Finns that they are part of the lore of the nation. The Finnish Disease Heritage has its own Web site.

“In school, children are taught that Finnish genes are slightly different,” Peltonen explained. “The textbooks and public press contain significant information about them. The search for the special selection of genes — actually they are alleles — is considered as a cause for pride.”

Clearly the Finns were an exceptional bunch, wedged at the top of the world between Sweden and Russia and speaking an odd tongue that is unrelated to other languages of Scandinavia. Does all of this make Finns a race?

“How do you genetically define race?” Peltonen answered, shaking her head. Race is used in biology for birds and animals — the term is tantamount to subspecies — but her studies had no use for it. Patterns of human variation can be linked to geography, and geographic ancestry can be linked to health risks. As a genetic explorer Peltonen has followed the movement of populations in history, knowing that genes had diversified during the moves, but in Finland as elsewhere only a tiny fraction of the alleles and health risks are distinctive. “Race may fade away once we understand all the variants,” she said. “But for diagnostic purposes it will be useful to know where your roots are. That’s the value of the Finnish Disease Heritage. The story of these genes helps us visualize how Finland was settled.”

By convention the Finns are white or Caucasian. Peltonen was probably the palest person on Westwood Boulevard. Nevertheless, in the 19th century she would have been classed with the Mongol race because anthropologists of that day lumped Finns with the Laplanders, or Sami, as they call themselves — the nomadic, faintly Asiatic people who roam the Scandinavian Arctic. That’s how arbitrary “race” can be.

A Family Affair

Congenital nephrosis is a deadly kidney disease that crops up in Finland. To become ill, the patients had to inherit a gene variant from both parents. When geneticists traced their pedigrees back nine generations, they found that the parents of the patients were related through three individuals. Many grandparents of patients with congenital nephrosis lived in areas of Finland that were only sparsely settled after 1550, which made intermarriage among relatives more likely.

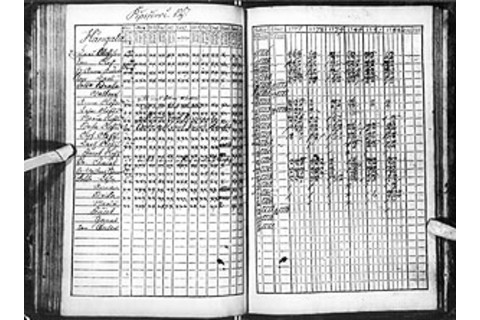

Church records, Northern Finland, 1777-1782: Registers from the Lutheran Church are a trove of information for scientists hunting for clues to the inheritance of Finland’s distinctive diseases. Voluminous congregational records document baptisms, marriages, moves, and deaths throughout the country between the 1700s and the 1960s. Geneticists use the registers to trace ancestry back 6 to 10 generations. (Credit: Courtesy of Reijo Norio)

Courtesy of Reijo Norio

Finland is a land of lakes and forests and rushing wind. Helsinki, the capital, on the southern coast, lies on the same latitude as Anchorage, Alaska. Finland extends as far north as Alaska, but the influence of the Gulf Stream makes Finland milder. Helsinki is not too different in appearance from other great cities of Europe. Its pool of DNA must be the most heterogeneous in Finland because Helsinki is a crossroads, past and present, to and from other peoples of Europe.

About 10,000 years ago, after the glaciers of the Ice Age retreated from the Scandinavian landmass, bands of hunters and fishers moved across the Baltic Sea and into the Finnish wilderness. Where in Europe these early settlers came from is debated. Blood-typing and genetic analysis link the Finns with other European groups, with maybe a bit of Laplander thrown in.

Most population geneticists agree that the main migratory stem, well before the budding of the Finns, has its roots in Africa. They also agree, if with less unanimity, that the most common genetic variants found in contemporary human beings are ancient in origin — at least 50,000 years old. It follows that the pioneers of Finland carried with them the propensities for all the common diseases plaguing people today, such as heart disease, arthritis, Parkinson’s, and asthma. These are called complex conditions because their genetic and environmental causes are multiple and murky. According to the “common disease/common variant” theory, it’s not necessary that the diseases themselves be old, just that the alleles, the predisposing variants, are old.

Two thousand years ago farmers inhabited the southern and western coasts of Finland. Then, as now, meat and dairy foods were the mainstays of the diet, all the more so in a land where raising crops was hit-or-miss. Then, as now, a minority of Finns would have trouble digesting the milk and cheese because of a gastrointestinal condition known as lactose intolerance. It’s caused by a gene variant that makes too little LPH, an enzyme that breaks down lactose.

Lactose intolerance occurs in populations around the world. In Asia and Africa rates are as high as 80 percent. The most frequent form of the disorder develops in adulthood. Nursing children are seldom affected because mother’s milk is vital for survival. By the same reasoning, northern people need the benefits of milk proteins more than other groups and therefore show relatively low rates of lactose intolerance — in Finland it’s about 18 percent.

In the late 1990s Leena Peltonen and her team, capitalizing on Finnish homogeneity, unlocked the key to the condition. They found that a tiny change in the sequence of DNA, a change of a single letter, from a C to a T, causes the gene to lose its capacity to make the enzyme. Peltonen found the identical alteration in groups and races who by geography were far apart. That finding suggested that the allele occurred before human populations branched out from Africa.

Adult lactose intolerance appears to have been the normal condition for Homo sapiens 100,000 years ago. The mutation that the majority of Europeans carry, the version of the gene that allows them to eat ice cream and crème brûlée without distress, emerged later. Initially the people who drank milk from cows had something unusual about them, but by chance the new allele improved the welfare of human beings on their way north. The gene helped a pale-skinned strain of farmers adapt to the European winter, when agriculture failed.

Peltonen likes this story because it shows how DNA drawn from a small corner of the world contains a message of universal significance. The story also demonstrates, with a twist, the common disease/common variant theory. The alleles for lactose intolerance and lactose tolerance represent time-tested genes of the human race, just the opposite of the alleles of the Finnish Disease Heritage, which are native born and recent.

During the 1500s about 250,000 Finns inhabited the coastal zone of what was then Swedish territory. Concerned about the unguarded border with Russia, King Gustav of Sweden induced Finns to migrate north and east into the pine forest. After the colonists established small farms and villages along the eastern frontier, immigration stopped, and the region remained isolated from the rest of Finland for centuries.

With an initial population in the several hundreds, the situation was ideal for what geneticists call genetic drift and founder effects. Mutations that were too scarce to make a dent on a larger population were enriched in the small but expanding group of people in East Finland. Most of the disorders that transpired were recessive, meaning that two copies of a flawed gene had to be inherited, one from each parent. Although people did avoid marrying their relatives, after 5 to 10 generations it was almost impossible that bloodlines would not have crossed in spouses from the same area.

From Helsinki to the Kainuu district in East Finland the distance is some 300 miles, pleasantly covered on smooth highways. In the last half of the journey the road passes banks of purple lupine, thick stands of conifer and birch, big clean lakes with a cottage or two on the shore, fields with little hay sheds in the center, then more woods and more lakes and more fields. The landscape, like the DNA, is homogeneous. The only exclamation points are the tall steeples of the churches, one for each widely spaced town.

About 400 years ago a new gene arose in the Kainuu district, an allele with no ill effect on its bearer, who was either a man named Matti or possibly Matti’s wife. In later generations, when a child received a copy of the gene from each parent, it seeded a disease called Northern epilepsy. Reijo Norio, a physician who has chronicled the Finnish Disease Heritage, refers rather fondly to Northern epilepsy as “an extremely Finnish disease.” Its symptoms were first described in a 1935 novel that takes place in Kainuu. A character, a beautiful and intelligent boy, developed “falling sickness” and “lost his wits.”

When Aune Hirvasniemi, a pediatric neurologist at the local hospital, began to track the disease in the late 1980s, she found 19 patients in a handful of families. No one had connected the cases before. Hirvasniemi consulted the records of the Lutheran Church, which for 250 years had written down the comings and goings of Finns in each parish. Creating a medical pedigree for Northern epilepsy, she followed it all the way back to its founder, Matti. She published her discovery of the epilepsy in 1994, the same year that researchers in Finland identified its gene on chromosome 8.

Hirvasniemi is a smiling woman with penetrating blue eyes. “I studied this because I wanted to show something new,” she said modestly. “It was not my daily work.” Indeed, after earning her Ph.D. in medical genetics on the strength of the find, the doctor resumed her pediatric rounds, shunning awards and speaking invitations. She had not heard of any new cases of Northern epilepsy in more than a decade, which she believed was partly because Finns now migrate out of Kainuu, an economically depressed region. At least half the hay sheds in the fields are abandoned and crumbling.

“But the gene is still alive in Finland,” Hirvasniemi said. About one in seven Finns is a carrier of at least one of the special disorders. Partly because of genetic counseling, but mainly because of luck, only 10 newborns a year are stricken with the distinctive conditions.

Norio, a medical geneticist, was an early investigator of the disease heritage. In the late 1950s he was a pediatrician like Hirvasniemi and curious about a lethal kidney condition that he named congenital nephrotic syndrome. Traveling around the country, Norio deduced its genealogy from family accounts and church records. Afterward he became a genetics counselor in Helsinki. Now semiretired, Norio receives visitors in his book-lined office and, over coffee and pastries, muses on the diseases that he calls “rare flora in rare soil.” He has written a book titled The Genes of Maiden Finland.

Other people might feel stigmatized by an unusual genetic heritage, but Finns take pride in it. That is something of a psychological turnabout. Like many people identified as belonging to a racial group, Finns used to be defensive about their biological identity, which was disparaged by their domineering neighbors. About the Mongol racial designation Norio wrote: “This characterization was then used as an abuse by those who wanted to repress the Finns into a lower caste. Today speaking about races is genetically out of date.”

Norio refused even to entertain the notion that Finns could be called a race of people because of their genetic idiosyncrasies. “Finns are just Finns,” he insisted, “a marginal population at the inhabited edge of the world.”

Finland’s genetic uniformity, which facilitates finding disease genes, has served science far beyond its borders. In an approach similar to Peltonen’s discovery of the allele for lactose intolerance, Juha Kere of the University of Helsinki and his colleagues have linked versions of Kainuu genes to asthma. A paper they published in the journal Science several months ago has gotten a lot of attention, because after detecting a suspect allele in Finnish families with asthma, the researchers found the same gene in families with asthma in Quebec.

Even more interesting, the allele is a variant of a gene that might actually be part of the disease process. In exploring complex disorders like asthma, diabetes, cancer, and heart disease, scientists can find genes that are associated with the condition: Such and such a gene is plucked out by computer analysis on the basis of its frequency. But that isn’t always terribly helpful, and it doesn’t necessarily grab the attention of pharmaceutical companies. Usually it’s but one of many genes associated with the disease, and often its function is unclear. The gene may be useful for diagnosing the condition or projecting the risk of disease in people who are healthy, but there isn’t a lot of profit in testing people.

The asthma gene found by Kere and his colleagues — which they immediately patented — is different because it expresses in bronchial tissue, where drugs might reach it. Investors and pharmaceutical companies noticed because asthma medications are a big business. With funding from foreign backers and the Finnish government, the scientists formed a small company, GeneOS, in Helsinki, where they are working on how the gene and its protein work.

Closed society: Finland’s population has grown tenfold since 1750, with scarcely any of this growth due to immigration. A study of a small Finnish village in the 19th century found that although few weddings occurred between cousins, half of the marriages were between village residents. (Credits: Original photo, Tiomo Manninen; Photomosaic®, Robert Silvers)

“It takes a long time to understand a new human molecule,” cautioned Tarja Laitinen, the chief scientific officer of GeneOS. Opening a freezer in the company’s small laboratory, she pulled out a test tube containing a grayish substance. It was pure frozen DNA — concentrated copies of the Kainuu asthma gene. “Investors are sometimes concerned that we [Finns] might be different,” Laitinen said. “Sometimes they ask: ‘Will a drug that works here also work in the U.S.? Shouldn’t we do the studies in the U.S.?’ So when we find the same haplotypes [blocks of DNA sequence around the gene] in Quebec, we are proving the common European root.

“Besides,” she added, “we’re too young as a species to be different. What’s different are the environmental factors.” What sparks asthma attacks in one society may not be the same in another.

Laitinen pointed out yet another advantage of doing science in Finland. “The strength for the Finns is both the homogeneous genes and the homogeneous environment,” she said. “Diets are similar. The same supermarkets are everywhere. In health care, people are treated the same everywhere.” This is useful because when environmental factors can be held constant in a study, genetic factors may surface more readily.

“When we were collecting blood samples in Kainuu,” Laitinen continued, “people knew that the benefits would be a long time coming. But Finland is a good place for medical research because people feel positive about it. ... So as a scientist I value the environment of Finland more than the genes.”

It’s a short walk from the GeneOS office to the National Public Health Institute of Finland, where Jaakko Tuomilehto heads the Diabetes and Genetic Epidemiology Unit. For 10 years Tuomilehto has collaborated with American investigators at the University of Southern California and the University of Michigan on a gene-mapping project for type 2 diabetes, formerly known as adult-onset diabetes. It’s a worldwide disease. Patients have numerous health problems because their blood-sugar levels are too high. Many eventually need insulin shots, like the children and young people who have the harsher type 1 diabetes.

The big-ticket item in the budget — $1 million a year — is to scan Finnish DNA for promising gene variants. That job is performed at the National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. Tuomilehto’s researchers enrolled subjects and collected blood from families throughout Finland.

“In the United States you are so heterogeneous you can forget about genetic studies,” he said. “There’s less of that here.

“Second, our records are the best. In most other countries the records are lousy if you want to trace back relatives. On my computer I can get, with the permissions that I have for each patient, the records on all past diagnoses, all hospitalizations and prescriptions. Also socioeconomic information like taxable income, ownership of a car, education, and marital status.”

Nonetheless, because diabetes is an extremely complicated disease, the results have been disappointing. “It’s difficult,” said Tuomilehto. “We realize we won’t get major genes quickly.” The gene variants that have been identified so far contribute only weakly to the risk of contracting the disorder. In other words, type 2 diabetes could never make it into the Finnish Disease Heritage, where a change in a single gene is decisive.

Given that the gene variants for diabetes may remain elusive for a while, Tuomilehto has concentrated on the environmental aspects of the disease. Obesity, he pointed out, is the leading risk factor for the condition. Genes interact with the environment. According to this view, whenever susceptible genes meet too many calories, weight goes up and diabetes follows.

That might help explain the postcard Tuomilehto has pinned to the wall behind his desk. It shows an enormous young man lying on his side on a beach. “Come to California,” it reads, “the Food is #1.”

When Finns brood over their history, their dark thoughts turn east, to the monolith of Russia. Throughout the 19th century, czars ruled the Finns. Under cover of World War I and the upheaval of the Russian Revolution, Finns declared their independence and made it stick, but the Soviets grabbed back a slice of territory after World War II. Only since the fall of communism have Finns been able to relax.

The border between Russia and Finland divides a region known as Karelia. Historians say the line has shifted nine times during the past 1,000 years, and no doubt genes have flowed freely as well. Compared with the Nordic-looking Finns, the Karelian type of Finn, according a source, is “shorter limbed, rounder faced, fair haired, gray eyed.” That could well describe a man named Aimo, who lives in the Kainuu district of East Finland.

Aimo’s last name is Karjalainen (“the Karelian”). He is 43 years old. He had a heart attack a year ago and a triple bypass operation last May, in which his prematurely diseased arteries were replaced by veins in his leg. In July he went for a checkup. An affable, muscular fellow, he indicated that he was recovering fast.

“Feels good,” Aimo said, which was the extent of his English. He unbuttoned his shirt to show the pink scar running down his chest. His mother’s family is from the Finnish side, and his father is from East Karelia, in what is now Russia.

In the 1970s the health authorities in Finland addressed an alarming statistic: Their country has the highest rate of mortality from heart attacks in the Western world. An intense public education campaign targeting the North Karelia district, just south of Kainuu, introduced Finns to low-fat diets. The campaign succeeded in lowering both cholesterol levels and heart fatalities. Yet the country’s physicians and researchers knew more had to be done.

“It’s my life’s work to solve the problem of heart disease,” said Jukka Salonen, an epidemiologist and gene hunter at the University of Kuopio. “Why do eastern Finns have the highest heart-attack mortality rate — in males — in the world? We still do. It’s come down, but ... ”

Salonen went to an easel and with markers charted the rise of deaths in the 1950s, their peak in the late 1970s, and then a decline to 2000. He drew the same curve lower down for the rates in southwestern Finland. Still lower down on the chart was a parallel curve for mortality over the same period in the United States.

“In eastern Finnish men there are risk factors — smoking, high-fat diet, high cholesterol and blood pressure, but they’re not that high,” he said. “We knew that in the 1970s. Today the differences between eastern and western Finns, in terms of diet, have disappeared.” Yet mortality from the disease in the east is still 1.5 to 2 percent higher. “More than half of the heart-attack risk is explained by other things,” Salonen said. “We think it’s genetic.”

As many as 500 genes might be involved in coronary heart disease, he said. “Half of them will be silent — they would have to be environmentally tripped.” That is, there would be interactions with changes in lifestyle, just as Tuomilehto’s diabetes genes have to be environmentally tripped. Many of the vulnerable genes — variants — may be the same for both conditions.

Salonen has led a 20-year study of coronary heart disease in Kuopio. With patented DNA chips and corporate backers, he is looking for alleles that distinguish healthy Finns from patients with a family history of heart disease.

In Kajaani, Aimo’s hometown, a squadron of public-health nurses is trying to get people to lead healthier lives. Also under way is a long-term study of 500 high-risk children to see if counseling parents about healthy cooking and exercise will reduce the death rates of the subjects when they become adults. To be high risk in the study is to have a father or grandfather who had a heart attack before age 55 or a mother or grandmother who had a heart attack before 65.

Aimo told the story of his health through his doctor, Juha Rantonen. The story was full of twists and turns.

Aimo had two jobs: one as a bouncer in a bar at night and the other as the owner of a gym. His heart attack was misdiagnosed at first as pain from a pulled muscle following an incident in the bar (Aimo had subdued a knife-wielding patron). But a friend took him in for tests. The cardiologists thought he might need only drug therapy, but after further review they called him back for the bypass operation.

Aimo had not known his heart was failing. He watched his weight and was not a smoker. His cholesterol was low. But he had been feeling weak and fatigued for three years. His father had a heart attack at age 50, and his grandmother died at age 70 from her heart condition.

Still, Aimo didn’t seem anxious. He was feeling better than he had for a while. What did he think about Finnish genes?

From his measured replies, it seemed that genes interested him more as wellsprings of the national character than as vehicles for illness.

“Finnish self-esteem,” Aimo said through his doctor, “is not good because we are squeezed between Sweden and Russia. But our language, our culture, our genes are unique. We should be more proud of ourselves.

“One black cloud only,” he stressed, opening his hands. “The disease genes. The rest is good.”

About the Series

This is the second of three articles exploring the relationship between race, genes, and medicine in three far-flung populations. Although race is a socially powerful concept, most geneticists think it has no foundation in biology. Modern DNA studies show that the world’s population is too homogeneous to divide into races.

But while dismantling the barriers of race, scientists have uncovered patterns of genetic mutation and adaptation in human populations. As archaic bands of Homo sapiens left Africa and spread over the world’s continents, their DNA evolved. Geography has left faint marks on everyone’s DNA. Although the differences are small, they show up in the diseases that different groups get and how these groups respond to drugs.

To measure these differences is not to resurrect race by another name but to emphasize the role of history in shaping medical legacies. Researchers seeking genetic explanations for health have to explore the events written in the record of DNA. In the first article about African Americans, geneticist Georgia Dunston points out that Africa contains the richest DNA diversity because it is the site of humanity’s oldest genes. Africans and their recent descendants in America may harbor clues to fighting diseases that other populations don’t possess.

The second and third articles follow gene hunters into more isolated and homogeneous gatherings of people — the Finns at the top of the European continent and the Native Americans in Arizona and New Mexico.

In the future, doctors will examine the genetic portraits of individuals, not populations. The path to understanding how individuals fit into genetically similar populations would run straighter if not for the old stigmas of race. Two of the three groups in Discover’s series, being minorities, are wary of genetic studies that may stereotype them further. In the past, science was not an innocent bystander when people were separated into races.