If you google “Where did coronavirus come from?” you’ll come across rumors that COVID-19 started in a lab. (It didn’t.) There are more movies, books and video games about unscrupulous scientists unleashing pandemics than you could shake a Purell-covered stick at.

But when asked to name an instance when a dangerous pathogen escaped a lab and infected the public, biosafety expert Allen Helm draws a blank. To his knowledge, it’s never happened.

“I don’t know of any evidence of any bugs that have gotten out,” says Helm, a senior biosafety officer at the University of Chicago. That’s in large part due to scientists whose job is making sure that dangerous viruses and bacteria don’t leave the lab.

Levels of Risk

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks biosafety hazards based on how dangerous they are and how easily they can spread disease. Level one might encompass working with blood samples from a healthy person. Level four would cover highly transmissible, fatal diseases like Ebola.

Helm primarily works with labs with level-two and level-three designations. The level-three labs he oversees study bacteria responsible for anthrax and the plague. The general safety principles, however, apply to any risky situation.

“The No. 1 way to never get hurt by a hazard is to eliminate it … If you never want to get hurt in a car crash, never set foot in a car,” says Helm.

But when it comes to research on infectious diseases, he says, “we believe that the risks are worth the benefits.” So scientists find ways to minimize those risks.

Read more: What Defines a Pandemic, and How Are They Stopped?

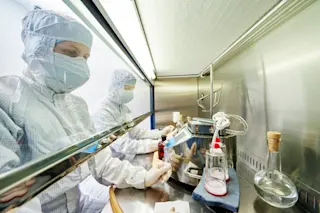

The obvious precautions researchers take include wearing protective clothing and using thorough cleaning practices — killing pathogens with alcohol and bleach and incinerating lab waste. But a lot of biosafety starts long before researchers enter the lab.

Behind the Scenes of Biosafety

To receive funding from the National Institutes of Health, labs must form biosafety committees — comprising scientists and laypeople — to review research proposals and assess risks to the public. Inspectors then conduct ongoing yearly inspections of equipment, policies and procedures to make sure the labs are following the guidelines set by the biosafety committee. Additional biosecurity measures — like fingerprint scans, cameras and scientist buddy systems — ensure dangerous bugs don’t get into the wrong hands.

Helm likens these behind-the-scenes security measures to car safety — wearing protective gear is like putting on a seatbelt. But seatbelt protection only goes so far. Road safety is rooted in a driver’s education, licensing and traffic law obedience.

That said, scrubbing into work at a biohazard lab takes a lot longer than clicking in a seatbelt. Researchers in level-three labs must wear full Tyvek suits and respirators, and shower before leaving work. Precautions get even stricter with more dangerous pathogens.

“At level four, you wear these moon suits — they’re very similar to what you’d wear in outer space,” Helm says. “There’s positive air being pumped in the whole time through a HEPA filter. The idea behind the positive pressure is that if [your suit] accidentally gets torn or ripped, air will blow out, and the bug won’t get inside the suit.”

These precautions serve a dual purpose: “Not only have you got to protect yourself, but you’ve got to protect the world,” Helm says.

Accidental Infections

However, the only way to guarantee you won’t get harmed by a pathogen is to avoid it entirely. Helm has heard of smaller-stakes pathogens leaving labs — at a teaching lab, for instance, scientists accidentally got infected with Salmonella and brought it home. Although serious breaches haven’t affected the public in decades, they can pose risks to the scientists themselves.

Dominique Missiakas, a microbiologist at the University of Chicago, studies the bacteria behind plague, anthrax and the antibiotic-resistant superbug MRSA. When asked if she ever worries about the risks of her job, she replies, “Always.”

Ten years ago, a colleague of Missiakas died after lab exposure to the bacterium that causes plague. His susceptibility was traced to an underlying genetic condition, and no one else was harmed. But Missiakas notes, “these pathogens are present in the environment. We’re trying to learn how to limit the dissemination to humans, and this has only happened through research that we do in the labs.”

Helm also emphasizes that the dangers of working with these pathogens are worth it. Studying viruses and bacteria helps us learn how to fight them.

“We've eradicated two pathogens from the planet, smallpox and rinderpest. Polio’s coming close. And you could not have done any of those things without playing with the bug,” says Helm. “Every vaccine that comes out is because somebody was working with biohazards.”