Ian Burkhart was 19 when he broke his neck, leaving him a quadriplegic, paralyzed and unable to move his upper body from the elbows down. Now, six years later, he can control his fingers enough to play the video game Guitar Hero. And it’s all thanks to a so-called neural bypass.

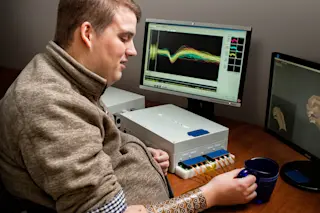

Burkhart is the first person to undergo this procedure, reported by Battelle Memorial Institute and Ohio State University researchers in May in Nature. Ninety-six electrodes were implanted in his brain, and his arm was wrapped in an electrode-studded cuff. Following hours of practice, a computer learned to identify brain signals associated with different wrist and finger movements. And unlike in other techniques, which send these signals to a prosthetic limb, the computer routed the signals directly to Burkhart’s actual muscles, electrically stimulating them via the cuff.

The equipment is restricted to use inside the lab. But future versions might ...