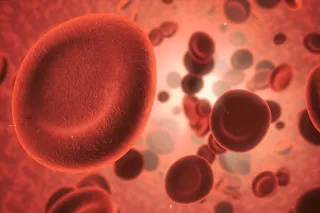

Bright yellow. That was the first thing I saw as I opened the door to the room of my 1-year-old patient, Reza. He sat on his father’s lap across from me. Dark brown hair fell across his forehead, and the whites of his eyes glowed with the brilliant yellow of a highlighter marker. His skin’s dark complexion was also tinted a dull yellow, producing the sallow cast of dead grass. Reza’s father bounced him daintily on his knee to help keep him calm.

Physicians call yellowing of the eyes and skin jaundice, a term from the French jaune, meaning “yellow.” During my pediatrics training, I saw innumerable cases, almost all of them in newborns. But Reza was no newborn, and seeing that familiar yellow on a much older child told me something unusual was going on.

“When did he turn yellow?” I asked his parents, pulling up a stool. His ...