Andrew Weil looks comfy. Clad in a hemp-fiber sports shirt and grungy cotton gardening pants, he's kicked off his boiled-wool clogs, propped his bare feet on his desk, and is on the phone, fielding personal questions from callers for his popular Internet audio program DocTalk. Bob seeks relief from ulcerative colitis; Weil suggests quaffing a slurry of aloe vera, activated charcoal, powdered psyllium seed, and acidophilus. Susan suffers from sinus headaches; Weil advises acupuncture. Elaine wonders if a purported natural breast-enlargement product made of eight organic herbs will promote a "womanly" figure; Weil doubts it. "Breast size is mostly genetically determined," he says. But the bad news goes down easily; Weil's basso is as warm as the Tucson, Arizona, sunshine outside his home office.

Some 2,300 miles away, on a drizzly afternoon in Philadelphia, Arnold Relman looks aggravated. Wearing a dark business suit and tie, the editor emeritus of the New England Journal of Medicine maintains a proud professorial posture as he rails against the Weil menace at the “Science Meets Alternative Medicine” conference—essentially a 200-person support-group meeting for alternative-medicine bashers. “Weil is devious,” Relman says. “He’s a manipulator. He’s a zealot, and a lot of what he says is just off the wall.” Relman’s colleague Wallace Sampson, clinical professor of medicine at Stanford, projects a slide depicting a huge pile of human excrement and a can of shoe polish. The slide sums up the conference’s thrust: Alternative-medicine proponents in general—and Andrew Weil in particular—don’t know one from the other.

Weil and Relman exemplify the escalating war for the soul of American medicine. Allopathic medicine—the modern drugs, surgery, and high-tech regimen of most M.D.’s—is under assault by a bewildering variety of so-called alternative therapies. Fed up with what they view as a heartless, invasive, confusing, expensive, and sometimes even deadly medical system, patients are swarming to chiropractors, naturopaths, herbalists, acupuncturists, and other formerly out-of-the-loop practitioners; in 1997, more Americans visited an alternative therapist than a primary-care physician. Meanwhile consumer demand for herbal medicines is skyrocketing; the American Botanical Council estimates 1997 sales at nearly $4 billion.

Even the medical establishment itself is changing. These days, 118 of the nation’s 120 medical schools offer courses in alternative therapy. Insurance companies are increasingly reimbursing for hypnotherapy, acupuncture, and similar once-fringe therapies.

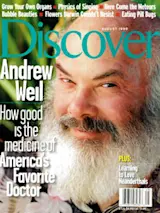

How much of this change can be attributed to Weil? “The culture just caught up with me,” he says. But as a bona fide, Harvard-trained M.D., Weil has used his credibility to do plenty of pulling. His eight books have sold 6 million copies. Time magazine splashed his Santa-bearded face on its May 12, 1997 cover and later named him one of the 25 most influential Americans. “Andrew Weil’s Self Healing” newsletter has 450,000 subscribers; his Web site (www.drweil.com) garners a half-million hits per week. To anyone teetering between, say, St. John’s Wort and Prozac to ease depression, Weil’s imprimatur on the herbal choice can easily be the deciding factor.

Weil’s influence continues to spread because he’s claimed the middle ground. Much of alternative medicine is a nut farm, featuring warmed-over nineteenth-century quackery that ranges from worthless to lethal. But hard-core allopathic medicine has its own hall of shame: profit-driven research that virtually ignores unpatentable plant-based medicines, antibiotic overkill that yields invulnerable super-pathogens, and—according to a lead article in the April 15, 1998 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association—an estimated 100,000 deaths a year in U.S. hospitals directly caused by adverse reactions to pharmaceutical drugs.

Weil espouses what he calls integrative medicine, which aims to cherry-pick the best therapies from all medical philosophies. He embraces the utility of high-tech medicine, particularly for emergencies. “If I were hit by a truck, I’d want to go to a modern emergency room,” says Weil. But he contends that “gentler, nature-based systems” can shore up, and in some cases replace, allopathic treatments, especially for chronic conditions such as skin problems, autoimmune disorders, and gastrointestinal-tract illnesses—the very conditions allopathic medicine seems largely helpless to remedy. And many of his healthy lifestyle recommendations—exercise daily, eat high fiber and low fat, take vitamins, and practice stress reduction—have been widely, if belatedly, embraced by mainstream physicians.

So, increasingly, the zeitgeist is Weil’s, but the medical establishment is fighting back. In her keynote address at the Philadelphia conference—which is rewarded with a standing ovation—Marcia Angell, executive editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, proclaims that alternative medicine is inferior, but popular because it is user-friendly. “Visits are leisurely, and treatment is gentle. It is also empowering. People are said to heal themselves,” she says. “People assume alternative medicine is better because it feels better to get it.”

Angell adds, “People who dislike science—and that’s a lot of people—are drawn to alternative medicine. Science is hard. How nice not to have to deal with anatomy, physiology, pathology, and the rest.” Most Americans, Angell says, are content with a “gloss of science. So when skeptics ask for evidence, advocates of alternative medicine can throw at them some gibberish about quantum mechanics.”

What rankles Relman, Angell, and other critics about Weil in particular is his tendency to speak ex cathedra: to endorse therapies based only on anecdotal evidence rather than on scientific research. As Weil’s star has risen, so have attacks on his veracity. The most resonant recent broadside was Relman’s “A Trip to Stonesville” in the December 14, 1998 issue of the New Republic. In the article, he hammers Weil’s tendency to trumpet single-case, credulity-stretching alternative-therapy cures—such as bone cancer thwarted by diet and exercise, or scleroderma healed with vinegar, lemons, aloe vera juice, and vitamin E—without providing “anything resembling scientific evidence.”

Having dispatched the last caller on his Internet audio program—Mark had whiplash; Weil recommended osteopathic manipulation, acupuncture, and massage—Weil leans back, rubs a hand over his famous bald pate, and considers Relman’s objection. “My point was not that you can cure scleroderma with lemons but to make people aware that there is a potential for scleroderma to be healed,” he says. “Same with bone cancer. Being aware of these kinds of healings can inspire people that there is hope, and to search for something that might work for them.”

As for the science behind alternative medicine in general, “The peer-reviewed research is coming. The body of evidence is growing every day, particularly for botanicals and mind-body medicine,” says Weil. One example: A consensus panel convened by the National Institutes of Health, after reviewing medical literature, concluded in November 1997 that “there is clear evidence that needle acupuncture treatment is effective for postoperative and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting, nausea of pregnancy, and postoperative dental pain.”

“Medicine has always operated in uncertainty,” says Weil. “The Office of Technology Assessment of the U.S. Congress estimated that fewer than 30 percent of procedures currently used in conventional medicine have been rigorously tested. While waiting for further tests, we do the best we can, trying not to hurt people, trying to make educated guesses.”

The term anecdotes, continues Weil, is trivializing: “It suggests some old codger sitting on a porch telling a story.” Weil prefers to call what he has seen “uncontrolled clinical observations.” In a written response to Relman’s critique, Weil noted that the University of Arizona recently landed a $5 million National Institutes of Health grant to study, among other things, the value of cranial therapy (manual manipulation of the skull bones) in treating children’s ear infections. “If I had dismissed the successes I saw with [the treatment] as anecdotes, we would not be in a position to take the next step and gather the data that Relman wants to see.”

Of the doubting chorus in Philadelphia, as well as other conventional doctors, Weil says, “The image I have is of a group of dinosaurs munching plants in the swamp. Suddenly, halfway around the earth, the asteroid hits. Thump! They look up. They know something has happened to them, but they don’t know what it is.”

Andrew weil awakes at 6 a.m. in his four-bedroom circa-1923 ranch house, some 25 miles southwest of Tucson. His surrounding 80 acres are surpassingly gorgeous; dapple-shaded by Aleppo pines and Arizona cypresses, dotted with spiny ocotillo and bushy chaparral (an infusion of the plant’s leaves, Weil says, is a fabulous palliative for eczema). He feeds his rambunctious trio of Rhodesian Ridgeback dogs, then meditates for 20 minutes, using the Vipassana technique, in which the practitioner focuses on his breath. After a breakfast of granola and organic raspberries—no milk—he gulps a multivitamin pill that he helped formulate (no iron, high in antioxidants), then downs a spoonful of vitamin C powder. He swims for 20 minutes in his backyard pool before buckling down to writing in the ranch’s former stable, now converted to a rustically stylish office and conference building.

At 56, Weil is robust and energetic and claims to “feel pretty good” virtually every day. That’s fortunate, as every day is a full day. “My publisher sees me as a cash cow,” Weil says. Prodding him for milk, Knopf has contracted him to write two more books: the first on nutrition, the second on aging. His assistant fields up to 500 letters a week, mostly from patients begging him for treatment. But his major aim these days is to drag integrative medicine into mainstream medical credibility. At the University of Arizona, where he is a clinical professor of medicine, Weil directs the two-year-old Program in Integrative Medicine. He supervises eight doctors in a teaching clinic he hopes can be a model for future medicine.

Weil also serves as editor in chief of a two-year-old scientific journal, Integrative Medicine, which examines research on acupuncture, homeopathy, chiropractic therapies, and herbal remedies. A typical article: a review by Jay Udani of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center of a double-blind study comparing ginkgo biloba, a leaf extract, with the synthetic drugs commonly used to forestall Alzheimer’s-induced mental deterioration. The conclusion: Ginkgo biloba “appears to be a safe and effective alternative to the current therapeutic alternatives for the treatment of dementia” and has fewer side effects than Tacrine, a popular prescription medicine for the condition.

Critics of alternative medicine have their own journal: the Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, edited by Wallace Sampson of Stanford and published twice yearly since the fall of 1997. The first issue blasts Weil’s best-selling book 8 Weeks to Optimum Health. The reviewer, John Renner, clinical professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, decries Weil’s “litany of directives: Eat organic food, do not drink tap water, breathe right, reduce your stress, exercise, take lots of vitamin C, eat a lot of garlic, move your clock radio away from your bed, buy some flowers, sweat a lot, drink green tea, avoid the daily news. . . . ” Renner concludes that this “mountain of opinion unfortunately comes with poor documentation of validity or effectiveness. He tosses off statements like ‘Supplemental vitamin C is nontoxic.’ But where is his evidence for that? At any dosage? For all persons? For any length of time?”

“That one is settled,” says Weil, who advises taking 250 milligrams of vitamin C twice a day. “The Linus Pauling Institute has all the data. There are certain individuals who are predisposed to form oxalate kidney stones, but that is rare, and overall health benefits, I think, are clear.”

PATIENT, HEAL THYSELF

Weil believes taking positive control of your daily life is the ultimate key to good health. To reduce susceptibility to illness, he suggests experimenting with each of the following lifestyle changes:

* Throw out all oils other than olive oil, all artificial sweeteners containing saccharin or aspartame, and all products containing artificial coloring.

* Buy some flowers for your home.

* Eat whole grains.

* Try green tea as a substitute for coffee or black tea.

* Try a one-day “news fast.” Do not read, watch, or listen to the news for one day.

* Take vitamin C, 250 milligrams twice daily; vitamin E, 400 international units daily if you’re under 40, 800 if you’re over 40; selenium, 200 to 300 micrograms daily; mixed carotenes, 25,000 international units daily.

* Never drink any water that tastes of chlorine. Never use hot tap water for drinking or cooking.

* Buy or grow organically produced fruits and vegetables. Be wary of pesticide-laden strawberries, bell peppers (both green and red), spinach, cherries, peaches, Mexican cantaloupes, celery, apples, apricots, green beans, Chilean grapes, and cucumbers.

* Make a list of friends who make you feel more alive and happy. Spend time with one of them this week.

* Eat at least two meals of fish and two of soy protein weekly.

* Eat more garlic.

* Observe a moment of gratitude for your food before your meals, in any way that you find comfortable.

* For five minutes daily, sit quietly and observe your breath.

* Volunteer for a few hours at a hospital or charitable organization.

* Reach out and connect with someone from whom you are estranged.

* Walk for exercise, building up to 45 minutes, five days a week.

Weil concedes that evidence for many other promising alternative therapies remains thin, but he says he’s encouraged that the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (nccam), a branch of the National Institutes of Health founded in 1992, has a $50 million budget. In 1998, the group funded 43 studies, including investigations into the effect of acupuncture on alcoholism, the value of melatonin in Parkinson’s-induced sleep disorders, and the efficacy of “calming music and hand massage on the agitated elderly.”

Weil’s detractors argue that recommending unproved therapies in the meantime is the height of irresponsibility. Weil’s response: “That’s absurd. In our clinic at the University of Arizona, we see a lot of breast cancer patients. This is an epidemic in this country. It’s also a tough disease to treat, surrounded by a great amount of medical uncertainty. I have seen several women who recently had recurrences, and they were really being pushed by their oncologists to do bone-marrow transplants. This is big time allopathic medicine, very expensive and not without risk. So we went to look up the statistics, the evidence, and it just is not there. But these women were being told, emphatically, that this is the way to go.”

Karen Koffler, an internal-medicine specialist who interrupted an established career—and sacrificed an estimated $150,000 a year—to practice and study at Weil’s clinic, adds: “The notion that everything allopathic medicine does is backed up by evidence is nonsense. We put patients on Heparin, a blood-thinning medication, after a heart attack. No one, as far as I’ve found, has rigorously tested that, and we’ve been doing it forever. People would be surprised to realize how much of allopathic medicine is just folklore that’s been handed down. We believe it has been studied along the way, but when you go back and really look, you find that it hasn’t.”

Critics say conventional medicine is a culture of conformity. Stressed out, sleep-deprived, and hectored by the specter of malpractice, physicians prescribe standard remedies by the lab-test numbers, acting out of sheer self-preservation. Weil revels in nonconformity. “All my life,” he says, “whenever someone would tell me, ‘This is how it is,’ I would think, ‘I’ll bet there’s another way.’”

Independence came naturally to young Weil, an only child who spent much of his early life alone while his parents ran a wholesale and retail millinery business in Philadelphia. At age 17, he spent nine months circling the globe as part of an international exchange program, living with families from Thailand to India to Greece. He says the experience showed him the Western world had no monopoly on truth: “This was the late 1950s, when American culture was deeply asleep.” Weil realized “there were entirely different ways of ‘doing reality.’”

A gifted student, he scored high on advanced placement exams, allowing him to enter Harvard with sophomore standing. He wrote for both the staid Crimson and the irreverent Lampoon, experience that has served him well. “Being a trained writer is almost an unfair advantage in the medical profession,” he says. He hopscotched between majors and eventually garnered an undergraduate degree in biology, specializing in botany. “It’s very unusual for a botanist to become an M.D.,” Weil says. “The two worlds seldom meet.” Later, as a student at Harvard Medical School, he helped conduct some of the first controlled human experiments with marijuana.

After receiving his medical degree in 1968, Weil gained a cult following among the drug cognoscenti for a trio of books: The Natural Mind, The Marriage of the Sun and Moon, and Chocolate to Morphine (coauthored with Winifred Rosen). In all three, he laid out his premise—bolstered by personally ingesting psychoactive mushrooms, yage, datura, pulque, mda, pcp, marijuana, cocaine, and coca—that there are no good or bad drugs, just good or bad relationships between people and drugs. While he still holds that belief, “The only recreational drug I use now on a daily basis is green tea. I drink alcoholic beverages very occasionally and eat chocolate once in a while.”

Among his most formative lessons gleaned from years of globe-trotting among native cultures was what he called the “wonderful relationship” between the Cubeo peoples of remote eastern Columbia and coca, the leafy shrub from which cocaine is derived. The Cubeo enjoyed the mild euphoria and endurance the powdered coca leaves provided but showed no signs of addiction and used it into healthy old age. Weil himself ingested it (snufflike, between the cheek and gum) almost daily during his three-week stay with the Cubeo and found it “tasty and pleasantly stimulating, [but] I developed no craving for it, no desire to increase the dose, and no sense of becoming tolerant to the effect.” The experience was one of many that persuaded him that Western reductionist pharmacology—isolating and synthesizing active elements rather than using the whole plant—was foolhardy. “These complex arrays of similar compounds that plants produce have a unique biological effect that cannot be ascribed to any single component,” he says. “When you present the body with these arrays, the status of the cell receptors determines which effects predominate. This could explain why some Chinese herbs can both lower high blood pressure and raise low blood pressure, which drives Western researchers nuts.”

In 1973, Weil settled in a remote canyon near Tucson, working as a wellness counselor at Tucson’s tony Canyon Ranch spa and gradually sought, through books and lectures, to naturalize the great juggernaut of Western medicine. Spontaneous Healing, published in 1995, catapulted him to international fame (in Japan, two of Weil’s books have topped best-seller lists, and he’s credited, ironically, with reintroducing traditional Asian medicine).

Increasing demands on his time exacted a personal price. In 1990, at age 47, Weil married for the first time, but divorced last year—his former wife, Sabine Kremp, 7-year-old daughter, Diana, and three stepchildren now live in Utah. “I’m just starting to come out of the emotional turmoil,” he says.

His critics intimate that money motivates Weil—in the New Republic article, Relman contends that Weil “directs a large and astonishingly successful medical marketing enterprise that might be called ‘Andrew Weil, Inc.’” But Weil’s life is hardly lavish, and he doesn’t rake in as much as he could. He still beats around Tucson in a five-year-old Toyota pickup, bats away dozens of lucrative offers to endorse various foods and herbal medicines, and last year gave $100,000 to the foundation that supports his clinic. Had he wanted to get rich, he contends, he could have used his Harvard M.D. back in 1969 to jump directly into some conventional, upscale medical practice—instead, more than a decade later, he was still too broke to fix his washing machine.

“If I wanted money, I would not be working half-time for a state university,” Weil says. While his book sales have been brisk, “I have no interest in accumulating wealth. It’s a by-product of what’s happening. I guess ego is a part of it, but I really do this primarily because I think it’s the right thing. The commonest feedback I get from people is, ‘It’s about time.’”

Marcia Angell, the Philadelphia conference keynote speaker, contends that many alternative therapies seem effective only because they are used “primarily by the worried well . . . young and healthy people who have trivial complaints. Most people stay well no matter what kind of treatment they get, and most illnesses are self-limited.” A good doctor, Angell says, will identify and treat serious illness, and tactfully suggest the patient wait out the self-limiting kind.

The greatest appeal of alternative medicine, Angell argues, is “not scientific or practical, but religious. Like most religions, alternative medicine has prophets—charismatic personalities like Deepak Chopra or Andrew Weil who explain its mysteries and embody the crusade. Instead of doing original research and publishing it in scientific journals, they promote their beliefs in books for the public. These works consist largely of inspirational testimonials glued together by pseudoscientific theorizing and advice that ranges from the banal to the ludicrous. The authority of the prophets rests almost entirely on faith and personal persuasiveness—how good they look on tv.” It’s all tragic, in Angell’s view, given that this century has seen life expectancy increase from 48 to 76, largely due to allopathic medicine’s advances.

Informed of Angell’s objections, Weil reflectively munches his lunch: a microwaved vegetarian burger with organic lettuce from his backyard garden. He’s heard the arguments before. “It’s just wrong,” he says.

Extended life spans in the modern era, Weil contends, “are primarily due to sanitation advances.” The notion that only the worried well tend to avail themselves of alternative care “just isn’t true. At the clinic we’re seeing significant pathology; people with complicated, end-stage, multisystem disease who have not been helped—or have even been hurt—by conventional medicine, and we’re getting good outcomes.”

IS THERE A DOCTOR IN THE HOUSE?

Weil recommends consulting a conventional allopathic physician to deal with the following conditions or situations:

* Traumas, crises, and emergencies

* Diseases involving vital organs

* Fast-moving, serious, virulent conditions. Of the 60 cancer patients seen so far at his University of Arizona clinic, “none was taken off any kind of conventional therapy, and 11 who said they would not do conventional therapy were persuaded by our fellows to do it,” he says.

* Difficult diagnoses

* Immunizations

* Reconstructive surgeries, such as hip replacements

* High-risk obstetrics

As for his serving as a stand-in deity, Weil concedes that gushing fans frequently accost him but emphasizes that to him, adulation is a penance he reluctantly endures for the chance to spread the word. “I promise you, I never wanted to be the alternative medicine guru,” he grumbles, shaking his head. “Once the clinic is really going, I have this fantasy of just being a gardener, or maybe opening a little café somewhere.”

But if he does—and nothing would delight the Philadelphia naysayers more—the movement he spearheaded will almost certainly go on. Last year, 80 doctors applied for four openings at his clinic. The patient waiting list recently hit 1,500, and several universities plan to clone the idea. Even if Weil stops writing, the integrative-medicine best-seller trail is blazed; other sympathetic M.D.’s are already following. For better or worse, Weil’s health-care agenda is woven—perhaps irrevocably—into the fabric of American medicine.

In Philadelphia, as the conference winds down, at least one participant seems weary of beating back a revolution that most patients seem to want. “People don’t deserve to have me worry about them,” grouses Saul Green, professor emeritus of biochemistry at the Sloan-Kettering Institute and a prolific author of journal articles critical of alternative medicine. “Andrew Weil has become a high muck-a-muck in people’s minds, and they do what he says. I say, fine—as long as people are willing to accept total responsibility for the consequences.”

But don’t expect Green himself to gulp ginseng or serve as an acupuncturist’s pincushion anytime soon. “I say, show me the evidence. Show me that it works. Then it won’t be alternative anymore.”