That insistent buzzing drone you hear? It’s the sound of our burgeoning mosquito problem and the nasty diseases that they carry wreaking havoc throughout the world. 2012 was a prodigious year for mosquito-borne arboviral diseases, with West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis, malaria, dengue and yellow fever outbreaks and epidemics raging in the United States, the Sudan, Puerto Rico, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Peru, Brazil and many other nations besides.

"Don't Mess With Texas," the road sign warning drivers throughout the State to not litter Texan roadways. This year, Texas had a more insidious mess on their hands. Image: Anne Ward. Click for source.

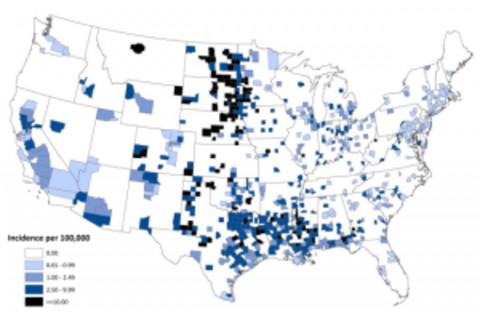

If you live in the US, you might know that this year the country suffered the largest outbreak of West Nile virus (WNV) since 2003. As of December 11th, infections with the virus have been reported in humans, birds and mosquitos in all of the lower 48 states. In humans, there have been a reported 5,387 cases of WNV disease with 2,734 or 51% of these cases classified as West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND), a severe manifestation of the infection resulting in encephalitis, chronic mental sequelae and occasionally death, and there have been 243 deaths; 80% of these cases have occurred in 13 states with a third of all cases reported in Texas (1).

Though it’s unknown why 2012 proved to be a particularly noxious and geographically expansive year for WNV in the States, there were several environmental factors that precipitated the outbreak’s emergence in Texas that may have influenced its severity. A short, mild winter at the tail end of 2011 may have allowed for greater numbers of mosquitos to survive the winter, an occurrence known as “overwintering”. In the spring and summer that followed, bouts of rain provided standing water for mosquito breeding and egg laying while droughts and higher than average temperatures may have also accelerated the replication of the WNV in birds and increased its transmissibility to mosquitoes, thereby augmenting its spread across the country (2)(3)(4)(5).

Dallas county in Texas has disproportionately suffered the majority of WNV cases and fatalities - 405 total cases of WNV disease and 18 deaths (6). Aside from auspicious environmental conditions for the mosquito population and the virus, the scale and severity of the outbreak can partly be attributed to the county’s inadequate dedication to mosquito surveillance and control, which led to several challenges to WNV disease prevention within the local population.

West Nile virus (WNV) neuroinvasive disease incidence reported to the CDC's arbovirus surveillance system ArboNET as of December 11, 2012, by county in the United States. Source: ArboNET. Click for more in-depth data and info. Dallas county did not follow their own established protocols for mosquito surveillance or the recommendations of mosquito experts, and decided to test mosquitoes for arboviruses in May rather than April despite the aforementioned environmental conditions. In doing so, the county failed to adequately evaluate the extent of WNV infection in the mosquito population (7)(8).

As the outbreak crescendoed over the early summer, the county had only a scant four employees dedicated to mosquito surveillance and control for an area 871 square miles wide and with a population of 1.2 million residing in Dallas city alone (7). The county administered a woefully low number of mosquito traps - one trap for every 19 square miles and only 20 traps per week - once more failing to either assess the magnitude of the mosquito population or properly identify the cities most at risk for transmission of mosquito-borne diseases (7).

Furthermore, Dallas county did not track and test deceased birds for the virus, a well-established and commonly used sentinel surveillance strategy for monitoring arboviral diseases in susceptible populations of wild and domestic animals (4)(8). Larvicide to treat egg-laden mosquito pools wasn’t purchased until July 30th, well into the beginning of the epidemic, “days after the CDC told the city’s health department that Dallas was already at the highest-possible risk level for West Nile virus." (8)

North Dallas neighborhoods sprayed in mid-July to kill mosquitoes carrying the West Nile virus. Image: Tom Fox at Dallas News. Click for source. Simply put, there were inadequate resources available for vector and viral monitoring in Dallas County and throughout the state oF Texas as a whole and, as a result, the mosquito population and the levels of WNV infection present in the population skyrocketed, all the while unbeknownst to local health officials. The outbreak only became apparent as escalating numbers of human infections were reported by local and state health officials to ArboNET, the CDC’s national database for monitoring arboviral infections in the populace, and the CDC in turn notified Texan public health officials. In the end, extreme and expensive measures had to be taken in the form of aerial and land pesticide spraying to staunch the numbers of increasing WNV infections and infection-related deaths. The WNV outbreak in Dallas county is a grim yet instructional example of the importance of active disease surveillance and institutionalized vector control programs. Surveillance - whether through monitoring the levels of tick populations or tracking the numbers of people reporting with flulike symptoms in emergency rooms - is the foundation of preventative public health. Without some truly simple and basic methods of tracking mosquitos and testing them for life-threatening diseases, we will again have outbreaks that can only be controlled by expensive, draconian measures that include using planes to shower urban cities with pesticide. Just a few short months after the outbreak that claimed 18 lives, Dallas county is now conducting year-round surveillance and testing of mosquitos to prevent another costly and deadly outbreak (10). Hopefully, the lessons learned in the 2012 outbreak will influence future public health efforts regarding mosquito and arbovirus surveillance in Texas in the years to come.

Full disclosure:

This article is adapted and modified from an essay on the investigation of the WNV outbreak in 2012 from a class I took last semester on outbreak epidemiology.

Note:

The information in this article is heavily reliant on the excellent investigational reporting by Scott Friedman at NBC 5. You can see an archive of his work for NBC, including his WNV investigative work, here.

Resources

A brief article in Emerging Infectious Diseases, "West Nile Virus Infection among Humans, Texas, USA, 2002–2011," found that WNV has become endemic in the state and the number of reported cases of infection increased every three years though that doubtlessly has changed following this year.

An incredible close-up and personal view of the eyes of a mosquito.

"Over one million people worldwide die from mosquito-borne diseases every year." Curious about what those are? Check out mosquito.org for their list of the nasty infections that mosquitos spread to humans, horses, birds and dogs.

The strange weather we've had this year - from droughts to monsoonal rainstorms to shocking heat waves - certainly played a role in the WNV outbreak in Dallas. The NYT talks about the new climatological reality in this superb article.

References

(1) CDC (December 11, 2012) “2012 West Nile virus update: November 20” CDC West Nile Virus Homepage. Accessed January 11, 2013 here

.

(2) JE Soverow (2009) Infectious Disease in a Warming World: How Weather Influenced West Nile Virus in the United States (2001–2005). Environ Health Perspect. 117(7): 1049–1052

(3) RM Kinney (2006) Avian virulence and thermostable replication of the North American strain of West Nile virus. J Gen Virol. 87(12): 3611-3622

(4) R Jaslow (August 24, 2012) "What's making the 2012 West Nile virus outbreak the worst ever?" CBS News [Online]. Accessed November 23, 2012 here.

(5) CDC (August 22, 2012) CDC Telebriefing on West Nile Virus Update. CDC Newsroom. Accessed November 23, 2012 here.

(6) Texas Department of State Health Services. (December 17, 2012) News Updates Webpage. Accessed January 11, 2013 here.

(7) S Friedman. (September 17, 2012) “Missed Opportunities in Fight Against West Nile Virus.” NBC Dallas-Forth Worth. Accessed November 22, 2012 here.

(8) S Friedman (September 13, 2012) “Dallas Revisits West Nile Virus Attack Plan.” NBC Dallas-Forth Worth [Online]. Accessed November 22, 2012 here.

(9) M Fernandez (August 16, 2012) “West Nile Hits Hard Around Dallas, With Fear of Its Spread.” The New York Times [Online]. Accessed November 22, 2012 here.

(10) J Stengle (December 26, 2012) "Health experts turn attention to learning lessons from historic West Nile outbreak." The Republic [Online]. Accessed January 11, 2013 here.

Soverow, J., Wellenius, G., Fisman, D., & Mittleman, M. (2009). Infectious Disease in a Warming World: How Weather Influenced West Nile Virus in the United States (2001-2005) Environmental Health Perspectives DOI: 10.1289/ehp.0800487