The first day of June 1988 was sunny, hot and mostly calm — perfect weather for the three young researchers from Canada’s University of Windsor hunting for critters crawling across the bottom of Lake St. Clair. A whining outboard pushed the 16-foot-long runabout carrying Sonya Santavy, a freshly graduated biologist, toward the middle of the lake that straddles the U.S. and Canadian border.

Myriah Richerson/USGS

On a map, Lake St. Clair looks like a 24-mile-wide aneurysm in the river system east of Detroit that connects Lake Huron to Lake Erie, and that is essentially what it is. Water rushes quickly through Lake St. Clair because it is as shallow as a swimming pool in most places, except for a roughly 30-foot-deep navigation channel down its middle. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers carved that pathway more than half a century ago as part of the St. Lawrence Seaway project to allow oceangoing freighters to sail between Lake Erie and the lakes upstream from it.

When water levels were low or sediment high, sometimes that channel still wasn’t deep enough, forcing ships to lighten their loads to squeeze through. This often meant dumping water from the ship-steadying ballast tanks — water taken onboard outside the Great Lakes. Water that could be swarming with exotic life picked up at ports across the planet.

As Santavy and her colleagues puttered over a rocky-bottomed portion of Lake St. Clair, she whimsically dropped her sampling scoop into the cobble below. She was hunting for muck-loving worms, but figured she’d take a poke into the rocks below because — well, to this day, she still doesn’t know. “I can’t even explain why it popped into my head,” Santavy tells me.

Up came a wormless scoop of stones, the smallest of which were not much bigger than her fingertips. But there was something odd about two of those tinier pebbles. They were stuck together. She tried to pull them apart but she couldn’t. Then she realized that one of them wasn’t a pebble at all. It was alive.

A young girl sits on a mound of quagga shells at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore in Michigan. Kim Schwaiger

The Zebra Invasion

Nobody gave it much thought at the time, but in the years following the Seaway’s opening in 1959, species not native to the Great Lakes, ranging from algae to mollusks to fish, started turning up at a rate never before seen. And the alien organisms continued to arrive, year after year, with an almost metronomic predictability — all the way up to that steamy Wednesday morning on Lake St. Clair in 1988.

Santavy showed a fellow scientist aboard the research boat her living “stone.” It was obvious to both of them that it was some kind of clam or mussel, but the dime-sized mollusk looked like nothing Santavy’s colleague had ever seen.

They sent it to the University of Guelph outside Toronto, where a mussel expert identified it as Dreissena polymorpha, the zebra mussel. This was not good news. The species, native to the Caspian and Black Sea basins, was well known on that side of the Atlantic for its ability to fuse to any hard surface, growing in wickedly sharp clusters that can bloody boaters’ hands and swimmers’ feet, plug pipes, foul boat bottoms and suck the plankton — the life — out of the waters they invade. The zebra mussel had already colonized rivers and lakes across Western Europe thanks to an extensive network of canals.

Biologist Sonya Santavy, who found zebra mussels in 1988. Michigan Department of Natural Resources

Scientists knew the most plausible way Santavy’s mussel could have made the trip across the Atlantic and into the Great Lakes was in the friendly confines of a freighter ballast tank.

The important thing about the zebra mussel is to not consider each one as an individual organism but instead, like a cancer cell, part of a greater scourge that metastasizes as fast as currents flow.

Each female can produce 1 million eggs per year. Those microscopic offspring — called veligers and as small as one-tenth of a millimeter in diameter — are covered with little hairs that help them catch currents and waves and “swim” to new locations during the first few weeks of their lives. The hairs also allow a baby mussel to snag food and begin to grow a shell, which eventually weighs it down and forces the mussel to settle on a lake or river bottom.

The North American zebra mussel problem was made worse by the fact that they have no worthy predators in the Great Lakes. In the most heavily infested areas, they soon began to cluster atop each other like gnarled coral at densities exceeding 100,000 per square meter. Each adult mussel, which typically grows no bigger than a nickel, can filter up to a liter of water per day, sequestering inside its hard little shell all the nutrients contained within that water.

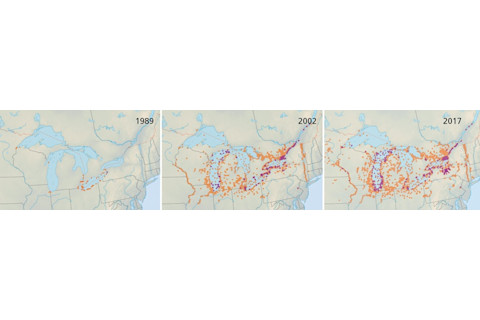

By the end of 1989, zebra mussels had turned up all across the Great Lakes, west to Duluth, Minn., south to Chicago, and east to the St. Lawrence River below Lake Ontario. A colony was also found near the head of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal that provides a man-made connection between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River basin. That meant the mussels now had access to a watershed that spans almost half of the continental United States.

Vodka-Clear Water

But the most ominous mussel development of 1989 made no headlines. Researchers on Lake Erie found what appeared at first to be a slightly different version of the zebra mussel. It was, they would learn two years later, the quagga mussel, named after a subspecies of actual zebras that went extinct in the 1800s. All that remains of the African savanna grazers are seven skeletons, including one on display at University College London. But today, their molluscan namesake numbers in the quadrillions in the Great Lakes alone.

The ecological damage wrought by zebra mussels is minor compared with their cousin, the quagga mussel. Unlike zebra mussels, which typically aren’t found at depths beyond 60 feet, quaggas have been plucked from waters as deep as 540 feet. This depth tolerance, coupled with the fact that quaggas don’t require a hard surface to attach to, means they can blanket vast swaths of lake bottom inaccessible to zebra mussels. Zebras also only feed during the warmer months. Quaggas filter nutrients out of the water year-round.

The public can comprehend the devastation of a catastrophic wildfire that torches vast stands of trees, leaves a scorched forest floor littered with wildlife carcasses and turns dancing streams into oozes of mud and ash. But forests grow back. The quagga mussel destruction is so profound it is hard to fathom.

Harvey Bootsma studies the Great Lakes from his home base in Milwaukee’s harbor. His team recently showed invasive mussels reduce Lake Michigan zooplankton — a key food — by half each year. Ernie Mastroianni/Discover

“People look at the lake and don’t think of it as having a geography. It’s just a flat surface from above,” says University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee ecologist Harvey Bootsma. “From there, it looks pretty much the same as it did 30 years ago, but underwater, everything has changed.”

The mollusks now stretch across Lake Michigan almost from shore to shore. People might still think of Lake Michigan as an inland sea full of fish. It’s more accurate to think of it as an exotic mussel bed sprawling across thousands of square miles. Lake Michigan’s quagga mass in one recent year was estimated to be about seven times greater than the schools of prey fish that sustain the lake’s salmon and trout. Under some conditions, the plankton-feasting mussels can now “filter” all of Lake Michigan in less than two weeks, sucking up the life that is the base of the food web and making its waters some of the clearest freshwater in the world.

This nearly vodka-clear water is not the sign of a healthy lake; it’s the sign of one in which the bottom of the food web is collapsing. One study on southeastern Lake Michigan revealed that by 2009, phytoplankton levels in springtime — the prime plankton-growing time of year — had dropped nearly 90 percent since the mussels took over the lake bottom. It’s probably not a coincidence that the lake’s fish populations have dropped at the same time.

Shifting the Baseline

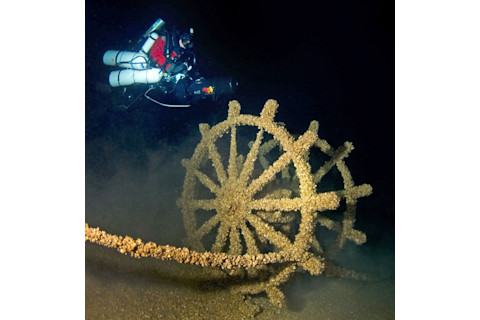

Even at 350 feet below the surface of Lake Michigan, the Carl D. Bradley’s stern wheel is encrusted in mussels. Mel Clark Photography

Not all fish are struggling, though. Take the invasive round goby, another Seaway interloper that arrived just a couple of years after the mussels and is also native to the Caspian and Black Sea region. It evolved to feast on the flesh of quagga and zebra mussels by cracking their shells with molar-like teeth. Now this bug-eyed, thumb-sized fish is thriving across the Great Lakes.

“People really don’t grasp what has happened here,” Bootsma explains to me on a frigid early November day as he straps on a scuba tank, climbs over the back of the boat and plunges to the lake bottom 30 feet below. He was only about 800 yards off the beach of a popular park in the leafy Milwaukee suburb of Shorewood. But he might as well have landed on another continent. Under the surface, Lake Michigan bears little resemblance to the freshwater wonder that left early European explorers awestruck with its teeming herring, trout, sturgeon, perch and whitefish. Down below, the lake has pretty much become just a goby show.

Bootsma finds the changes professionally interesting, but personally distressing. He attributes his whole career to summer days he spent as a child on Georgian Bay in northern Lake Huron, fishing for native bass and perch and snorkeling to the rocky bottom to capture crayfish. “I still remember telling myself that when I grow up, I’m going to get a job that will keep me on these lakes all the time,” he tells me.

Outside his office window at UW-Milwaukee’s School of Freshwater Sciences are the grain elevators and coal piles that define the city’s inner harbor. That harbor is connected to Lake Michigan, which is connected to Lake Huron, which connects to Georgian Bay. They all have different names, but in actuality they are the same lake, and the largest lake by surface area on the globe. It is no longer the lake Bootsma fell in love with. He’s known this for years because of his almost weekly trips out to his research station on the bottom of Lake Michigan.

What’s even more distressing for him is the idea that his children don’t even know what they’re missing. Ecologists call it the “shifting baseline phenomenon” — a fancy way of saying that kids are getting cheated out of the lakes their moms and dads loved. “This isn’t the lake it was 25 years ago, and it’s probably not the same lake it’s going to be in 10 years,” says Bootsma.

It’s not just native fish species and summertime beachgoers that have been hit by this biological pollution. Invasive species can have effects just as toxic as the nastiest chemicals concocted in a lab. A textbook example is the botulism outbreaks that have killed tens of thousands of birds on Lakes Michigan, Erie and Ontario. Mussels increase water clarity, which helps water plants bloom. When those plants decompose, it burns up oxygen, opening the door to botulism-causing bacteria that thrive in oxygen-starved environments. The mussels then suck up those bacteria and are, in turn, eaten by gobies, which become paralyzed and are easy prey for birds.

This is not a rare occurrence. Biologists estimate more than 100,000 dead birds — including bald eagles, great blue herons, ducks, loons, terns and plovers — have piled up on Great Lakes beaches since the botulism outbreaks turned rampant in 1999.

Shell Game

In 1993, the U.S. Coast Guard made exchanging ballast water with mid-ocean saltwater mandatory, yet wave after wave of new invasions kept rolling into the Great Lakes. The problem was about 90 percent of the ships arriving in the Great Lakes from foreign ports at that time came fully loaded with cargo and therefore did not officially carry any ballast water. But most tanks still carried loads of sludge — up to 100,000 pounds of it — along with thousands of gallons of residual ballast puddles that cannot be emptied with a ship’s pumps.

Subsequent studies revealed these muddy puddles swarmed with millions of organisms representing dozens of exotic species that had yet to be found in the Great Lakes. So by 2008, the U.S. Seaway operators began requiring all Great Lakes-bound overseas vessels to flush even their “empty” ballast tanks with mid-ocean saltwater. No new exotic organisms have been found in the Great Lakes since, a point shipping industry advocates tout.

And in 2011, the EPA finally mandated treatment systems for overseas ships discharging ballast in U.S. waters. The systems, which will use things like chlorine, ozone and UV light among other pesticides to kill ballast dwellers, will not be required of all ships until sometime after 2021. Although these treatment standards should reduce the amount of life spilling into the lakes from ballast tanks, think of the problem like a campfire. The EPA’s treatment requirements are a little like the first gallon of water you slosh on the fire at the end of the night. It might knock down the flames, but it will take several more gallons to properly soak the embers to ensure you’ve snuffed their glow.

In preparing ballast treatment standards, which a federal court ruled inadequate in 2015, the EPA turned to some of the country’s best scientists in the field to help establish a safe number of organisms that could be discharged per cubic meter of water while still protecting the Great Lakes and other U.S. waters from new invasions.

The only thing the panel could agree on is that the fewer organisms allowed to survive in a ballast tank, the better. Beyond that, they were at a loss because, they said, you can’t just pick a magic number and call it safe.

Unless the number you pick is zero.

That is the number Isle Royale National Park Superintendent Phyllis Green aimed for when she learned in 2007 that an invasive virus deadly to dozens of freshwater fish species was creeping toward her rugged, forested island in the middle of Lake Superior. Green’s focus instantly turned to the island’s coaster brook trout — a beleaguered native species that once numbered in the millions in Lake Superior but is now counted by the hundreds. “If you have only 500 fish and you have a disease that can kill fish by the tons,” she says, “your motivation is pretty strong, especially if your job is to preserve and protect.”

Green went straight to the captain of the Ranger III, the 165-foot-long ship that ferries park passengers to the island, 73 miles from its home port on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Worried that the ferry might suck the rapidly spreading virus into its ballast tanks while docked at the mainland, she asked if there were any way to disinfect that ballast before it was released into park waters. The captain said no. “What happens,” Green replied, “if I tell you that you can’t move this ship unless you kill everything in your ballast tanks?”

That’s when the brainstorming started. Green’s goal was to try to figure out how to make the Ranger III safe to sail — not in years or even months, but in a matter of days. She sat down with the captain, the ship’s engineer and David Hand, chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Michigan Technological University. Hand had worked on water purification systems for the International Space Station that can turn sweat and urine into tap water.

“This,” Hand told the group of the ballast problem, “is not rocket science.”

Two weeks later, Isle Royale’s passenger ship had a crude ballast treatment system that used chlorine to fry viruses and other life lurking in its 37,000-gallon ballast tanks, and then vitamin C to neutralize the poison so the water could be harmlessly discharged into the lake. Green didn’t stop there. She leveraged her authority as protector of Isle Royale to block all freighter ballast discharges within a 4.5-mile radius of the island, which happened to cover shipping lanes used by freighters sailing to and from the Canadian port of Thunder Bay.

The Park Service has since installed a permanent ballast treatment system on the Ranger III that uses filtration and UV light, a first for the Great Lakes. Although the Isle Royale boat is almost toy-sized compared with the freighters that ply the Great Lakes, Green contends the relatively simple chlorine treatment could be scaled up to the biggest boats on the lakes as an emergency line of defense that would be far stouter than the saltwater flushing — the only protection for the lakes until ballast treatment systems are required for all overseas ships, which likely won’t be until 2021 at the earliest.

Stop the Salties

The Great Lakes are wrapped by thousands of miles of shoreline. But unlike on the Atlantic, Gulf or Pacific coasts, there is, literally, a door through which every foreign Seaway ship must pass. Stop the overseas ships known regionally as “salties,” and you can stop their ballast invasions.

“Offload the cargo in Nova Scotia and ship it down through rail,” an exasperated former Chicago Mayor Richard Daley once told me. “That will protect the Great Lakes forever. That will protect local and state governments from spending hundreds of millions of dollars.”

He is not alone. Conservationists agree this low-tech solution for the Great Lakes could prove far cheaper than installing ballast treatment systems that could cost well over a million dollars on each ship.

Zebra mussels (orange) quickly colonized the Great Lakes and other waterways after they were first found in 1988. Quagga mussels (purple), which thrive in deeper waters, now cover vast regions of lake bed as well. Jay Smith

But what might it cost?

In 2005, two Michigan logistics experts took the first crack at putting a price tag on bringing in the Seaway’s overseas cargo into the region by other means. The figure they came up with was $55 million annually. That’s what it would cost to transfer the salties’ cargo from a coastal port to trucks, rail or regional boats.

The overall toll just to municipalities and power companies trying to keep their pipes mussel-free over the last quarter century tops $1.5 billion. And in terms of damage to fisheries and other recreational activities, the dollar toll for the ecological unraveling of the lakes due to ballast invasions was pegged in a 2008 University of Notre Dame study at $200 million annually — a number the study authors predicted would grow as new invasive species are discovered.

The question now is: How will the public respond once the next new invader turns up?

Cleveland’s industrially fouled Cuyahoga River burned over and over throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. As late as the 1950s, the flames on the oily surface of the water were still viewed as business as usual. But eventually the public had enough, and when the river was set ablaze in 1969, it turned a nation livid and led to passage of the Clean Water Act.

Isle Royale’s Green predicts similar fury with the shipping industry when the next ballast invader turns up. “The industry has had this grace period to find solutions,” she says. “The grace period they have been given will hit the fan when they find the next one.”

She tells me this on a raw, rainy day in 2014 at her park headquarters not far from the shoreline of Lake Superior, and my notes are a smudgy mess. When I go back to them later, I can’t tell from my scribble if she said “if” or “when” a new invasion happens. So I call her back to get clarification. She chuckles ruefully.

“No,” she tells me. “I said ‘when.’ Definitely ‘when.’”

Reprinted from The Death and Life of the Great Lakes by Dan Egan. Copyright © 2017 by Dan Egan. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.