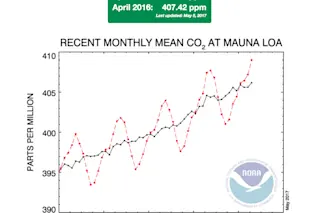

This graph shows carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere as measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. The last four complete years of the record plus the current year are shown. The dashed red line red line shows monthly mean values, and reveals a natural, up-and-down season cycle. The black line shows the trend after correcting for the average seasonal cycle. (Source: NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory) Back in late April, there was a spate of hyperventilating headlines and news reports about the increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This one in particular, from Think Progress, should have made its author so light-headed that she passed out:

That story and others were prompted by measurements at Hawaii's Mauna Loa Observatory showing that the concentration of heat-trapping CO2 in the atmosphere had exceeded 410 parts per million. Some of you might be thinking this: Since rising levels of greenhouse gases are causing global warming, and myriad climate changes like melting ice sheets and glaciers, then this really was big news story. And the highest CO2 level in 3 million years? WOW! That certainly justifies the hyperventilating hed, right? I don't think so. That's because the headline is inaccurate, and the story hypes the crossing of a purely artificial CO2 threshold. This may rile up the readers of Think Progress, but it does little to encourage broader public engagement on the issue of climate change. In fact, it probably does the opposite. Why do I think this? First, consider that four years ago, there was this headline on a Live Science story:

The Earth just reached a CO2 level not seen in 3 million years

Levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide hit record concentrations.

That story was published in 2013, when CO2 exceeded 400 parts per million for the first time. So which is it? Then or now? And also consider this: Fully eight years ago, when the CO2 concentration stood at 387 ppm, research showed that you had to go back roughly 14 million to 16 million years to find a time when CO2 was higher. Which brings me back to the Think Progress story that made a very big deal about CO2 reaching 410 parts per million. Why did they consider that number to be an important threshold — so important that they felt justified in dusting off that old figure of 3 million years and using it again? There's nothing particularly scientific about that threshold. The climate certainly didn't turn into a pumpkin on that day. And I have to wonder: Why didn't they do a story when it hit 405 ppm? Or why not publish something with every rise of 1 ppm?

Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Breaks 3-Million-Year Record

Atmospheric CO2 concentration, as measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory. (Source: NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory) And here's something else to consider: While daily CO2 readings at Mauna Loa reached 412.63 ppm on April 26th, that data point was something of an outlier, as the graphic at right illustrates. The average for that entire week was lower: 409.92 ppm. Since then, the weekly average has dropped even further. In fact, it's likely that CO2 has already reached it's peak for 2017 and will be declining through the Northern Hemisphere spring and summer. This naturally occurs every year, as growing vegetation draws CO2 from the air. (The Northern Hemisphere dominates the annual natural cycle of atmospheric CO2 because there is more land and thus greater vegetation there.) In September, as the leaves fall, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere will begin to rise again. And then come next May we'll see a new peak in CO2 that will exceed this year's. That's because the natural annual CO2 cycle rides atop the longer-term trend — the one that we humans drive largely through our burning of fossil fuels. My point is not that we shouldn't be concerned about continuing to use the atmosphere as a dumping ground for the byproducts of fossil fuel burning. Quite the opposite. We should be moving more aggressively to do something about it. If you have any doubts, check out the trend in sea level since 1880:

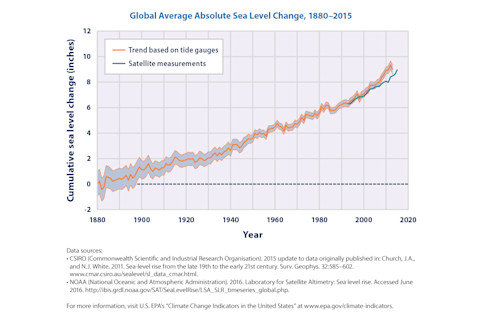

Cumulative changes in sea level for the world’s oceans since 1880, based on a combination of long-term tide gauge measurements and recent satellite measurements. (Source: EPA.) Moreover, sea level rise isn't something that only future generations will have to deal with. It's already causing significant challenges. If you doubt that, check out what's happening in Miami right now. So yes, we absolutely should be concerned about the rising tide of CO2 in the atmosphere, and doing something over the long run to transition away from fossil fuels. But hanging on every little uptick in CO2, and hyping multiple artificial milestones with appeals to fear, is journalistically suspect. Yes, CO2 probably is higher today than it has been for millions of years. But that was probably true back in 2009, as it was in 2013 as well. So why is this suddenly news again? Moreover, a large body of social science research shows that this approach can be decidedly counterproductive. For example, research published in the journal Science Communication found that "fearful representations of climate change" can produce these unfortunate outcomes:

People become desensitized to fear appeals

Fear erodes public trust in organizations making those appeals

Fear messages may cause people to believe that they are incapable of doing anything meaningful, leading them to deny what they are hearing, or to become apathetic.

I'm not saying that journalists should avoid writing stories about rising CO2 concentrations, how that is causing the climate to change, and what we should expect in the future. We should provide a clear and unflinching picture of what's happening, as well as information about possible solutions. In this way, we can help provide citizens with the resources they need to make up their own minds about the issues. But slapping an inaccurate, hyperventilating headline on a non-story to rile up readers is no way to do it.