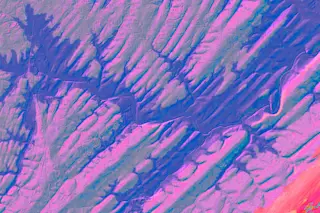

The magnitude 5.8 quake that struck central Virginia on Tuesday was felt from Florida to Maine to Missouri. “This is probably the most widely felt quake in American history, even though it was less than a 6.0,” says Michael Blanpied

, a USGS seismologist DISCOVER contacted after the event. The reason for this intensity is that the East Coast, like the controversial New Madrid Seismic Zone in the central U.S., is located amidst old faults and cold rocks in the middle of the North American tectonic plate, and seismic waves travel disturbingly far in such stiff, cold rock. We would do well to take a hint from Tuesday's expansive shake-up. It's lucky that it struck in rural America. But a similar tremblor in the crowded cities of the central U.S. above the New Madrid zone is a matter of when, not if. And the region is woefully unprepared to mitigate ...