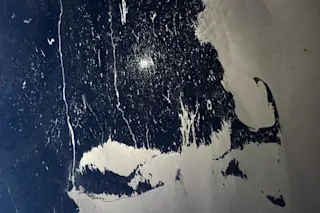

NASA astronaut Reid Wiseman Tweeted this photo he took from the International Space Station today. (The equipment in the foreground are solar panels that provide the station with electricity. Source: NASA/Reid Wiseman) In a Tweet today accompanying the photo above from the International Space Station, astronaut Reid Wiseman had this to say: "Odd square cloud runs into Kamchatka's volcano field." Look for it to the right of the solar panels. What's up with that weird cloud? Here it is again, this time in an image acquired today by NASA's Aqua satellite:

The Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East, as seen by NASA's Aqua satellite on June 12, 2014. (Source: NASA) From this perspective, the cloud is not really square. Even so, its eastern edge is rather sharply delineated. It runs right up to the coast of the peninsula (which is dotted with volcanoes) — and then just dissipates. Here's ...