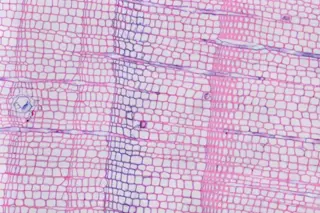

(Credit: krolya25/shutterstock) Wheat is one of the most widely cultivated cereals in the world. About 20 percent of the food humans eat has bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). As the world’s population grows, wheat researchers and breeders have been studying how to get even more out of the cereal. And some estimates say bread wheat production needs to increase by more than half in coming decades to feed everyone. To achieve this, scientists have been tinkering with wheat DNA to improve the health and production of this staple crop. But the challenge has been trying to assemble a complete wheat genome. Since 2005, the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) has been at the task, even releasing fragmented sequences. On Aug. 17, the consortium announced a sequence of 94 percent of the bread wheat genome, giving scientists access to nearly 108,000 genes of the cereal. The genes have also been identified ...

New Wheat Genome Sequence Could Unlock Hardier Crops

Bread wheat production is set to rise as scientists unlock nearly 94% of the wheat genome for improved strains.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe