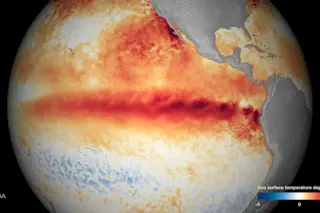

A spear of exceedingly warm sea surface temperatures projected across a large portion of the equatorial Pacific Ocean in early October — a signature of the strong El Niño event now underway. (Source: NOAA) Back in August, a respected NASA scientist told the LA. Times that conditions in the Pacific Ocean were pointing toward the potential for a "Godzilla El Niño." Meanwhile, a science blogger for the NOAA nicknamed it "Bruce Lee." Time has proved them right. The latest data released by the U.S. Climate Prediction Center, show that if El Niño continues to develop as forecast, it will go down as one of the most muscular on record. But really, who cares about data on exceedingly warm sea surface temperatures projecting like a spear across a large portion of the equatorial Pacific? (Okay, I do. See above.) Or the weakening of the trade winds along the equator? Or any ...

Godzilla, The Blob, and Son of Blob: an El Niño reality check

Discover the impact of the Godzilla El Niño on California's weather patterns and precipitation during this season.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe