But the stop-gap measure, now before Congress, includes a provision that some regard as a major step backward

Signs on the pole in this photograph (below) show how much the land has subsided due to pumping of groundwater in Arizona’s Wilcox Basin between 1969 and 2018. (Source: Arizona Department of Water Resources.) For the 40 million people who depend on water from the Colorado River Basin, including me, there’s no escaping this stark reality: Our thirst for water exceeds what’s actually available.

That’s mostly because rising temperatures are sapping moisture from the environment even as demand for water resources in the region is going up. The result: a run on the banks — lakes Mead and Powell, the two largest reservoirs in the basin. Collectively, they’re now just 40 percent full. For Lake Mead, that brings it perilously close to a critical threshold: Once its surface level is expected to drop to 1,075 feet above sea level, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will declare a first-ever water shortage in the basin.

This, in turn, would trigger significant mandatory cutbacks in water use imposed by the federal government. This isn’t just an issue for people who live the in the region. That’s because the river provides for a $1.4 trillion economy — which means that what happens here in the Colorado River Basin won’t just stay in the basin.

With all of this in mind, the seven states of the basin — Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming — have been struggling to reach agreement on contingency plans. The goal is to avoid the federal government dictating from the top down what will be done once the water shortage threshold is crossed. The efforts by the states to reach consensus have finally succeeded. And on March 19, 2019, they took a big step forward when they asked Congress to pass legislation giving them permission to put their plans — collectively bundled together into something called the “Drought Contingency Plan,” or DCP — into effect.

”It’s a remarkable achievement,” said Bruce Babbitt, former governor of Arizona and Secretary of the Interior from 1993 to 2001, speaking at a workshop on water issues I’m attending in Phoenix. “It’s a pain-sharing agreement.”

Through the overall Drought Contingency Plan, the seven states have agreed on ways to share the pain of cutting back their use of Colorado River water should that become necessary — as it almost certainly will in the next year or so. Babbitt’s own state of Arizona will take the biggest cut under the plan. To help salve the pain, the state is planning to do something that has generated quite a lot of controversy: pump more water from underground aquifers to allow farmers who would otherwise be cut off from irrigation water to continue growing crops in the desert.

More specifically, Arizona’s complex plan will provide at least $9 million to irrigation districts to enable them to drill new wells and related infrastructure. This would help them to eliminate their use of water from the Colorado River and rely instead on groundwater for irrigating crops. If that sounds good, consider Babbitt’s reaction: “Interest groups reverted to Arizona style: ‘We’re not going to give up anything — we want even more,’” Babbitt said.

This panorama showing nearly the full length of Lake Powell in southern Utah and northern Arizona was photographed by an astronaut aboard the International Space Station, on Sept. 6, 2016. The station was north of the lake at the time, so south is at the top left of the image. (Source: NASA Earth Observatory)

Arizona’s plan is ultimately a stopgap measure to deal with the overarching problem of living beyond the hydrological budget in this part of the world. Instead of balancing that budget, “we’re going back to pumping ground water,” Babbitt lamented. In the long run, that’s not sustainable. Aquifers are another kind of hydrological savings bank — and withdrawals can very easily exceed deposits.

One result is illustrated in the photo at the top of this post. It shows just how much the land has dropped as a result of groundwater being pumped out of the underground aquifer in one area of Arizona. That view from the ground dramatizes the degree of subsidence in a way that we can very easily grasp. But it doesn’t reveal the sheer scale of the issue. For that, satellite imagery is ideal.

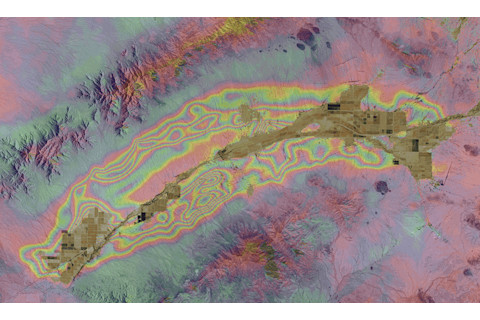

A satellite-based radar system was used to produced this “interferogram” showing subsidence of land in Arizona’s 650-square-mile McMullen Basin due to pumping of groundwater for agriculture. (Source: NASA) This graphic, called an “interferogram,” provides a broad perspective on subsiding land from groundwater pumping. It was produced by a satellite system that beams radar signals to earth and measures the bounce-back signals to determine how the land may have moved, up or down. The psychedelic fringes in the image reveal areas where land has subsided in Arizona’s McMullen Valley, an area larger than the City of Los Angeles, between April 2010 and May 2015. In some places, the land has dropped by as much as 10 feet during this five year period.

Over the longer term, subsidence has been even more jaw-dropping, with drops approaching 300 feet since the early 1940s! Seeing the impact of ground-water withdrawals, Arizona enacted a landmark law in 1980 – when Babbitt was governor — called the Groundwater Management Act. “At the time it was the most comprehensive such act,” said Jim Holway, Director of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy. “It was regulatory, which was a big leap for Arizona.”

The overall purpose: push the state toward sustainable use of groundwater over the long term. But it established different goals in different areas. In Pinal County, one of Arizona’s major agricultural regions, the primary management goal was to preserve the farming economy, leaving more room for pumping groundwater than in other management areas. Now, Arizona’s state-level drought contingency plan will encourage more groundwater pumping for irrigation in that county — arguably a step backward for a state that once tried to lead the way along a more sustainable path.

The Arizona plan “abandons some of our commitments to limit groundwater pumping,” said Sandy Bahr, director of the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club. “Not only does it allow more pumping but we’re also going to pay for it,” she noted, referring to taxpayers. Bahr points out that Arizona farmers commonly plant very thirsty crops like alfalfa and cotton. Switching to less water-intensive crops could help, yet the plan failed to address this issue. “The history of Arizona water is to really rob Peter to pay Paul,” she said.

Agriculture and suburban sprawl on the outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo: © Tom Yulsman) But Clint Chandler, Assistant Director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, points out that given all the competing interests in the state, reaching consensus on the plan was a major achievement.

“The groundwater piece is part of a big bundle, a compromise,” he said. “We wanted an agreement that could withstand scrutiny of the Arizona legislature.” Arizona was, in fact, the only state among the seven that had to get its drought contingency plan approved by the legislature. “Overall it is a very commendable thing that Arizona accomplished,” Chandler said. “It is a big deal.”

Ultimately, thought, the plan merely kicks the can down the road, temporarily forestalling the day when the imbalance in the region’s water budget causes even more pain. “We all live on budgets,” noted Stu Feinglas, the now retired Water Resources Specialist for the City of Westminster, Colorado. “If we don’t take an active part in managing these budgets, they will resolve on their own.”