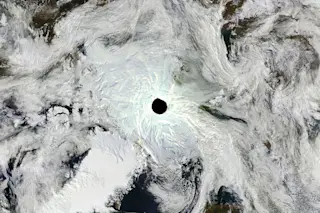

A mosaic of images from NASA's Terra satellite shows the entire Arctic region, centered on the North Pole (where the dark spot indicates missing data). The images were acquired on Sept. 17 — when Arctic sea ice likely reached its minimum extent for 2014. (Source: NASA) In 2014, Arctic sea ice has continued in its long-term and dramatic decline, a process that is likely helping to accelerate the pace of overall climate change in the north. That's the news from the National Snow and Ice Data Center, announced on Monday — just as world leaders were preparing to meet at the United Nations in New York to grapple with climate change. According to the NSIDC, Arctic sea ice — which floats atop the ocean — likely reached its minimum extent for the year on Sept. 17th:

This is now the sixth lowest extent in the satellite record and reinforces the ...