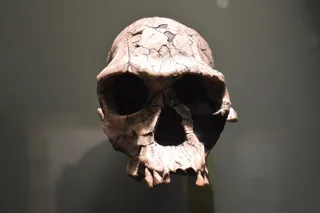

Neanderthals, the best understood species of archaic human, often lived in limestone caves that preserved their bones well after death. As a result, archaeologists have found many more of those bones than those belonging to the Denisovan species, a less understood but still important type of early human.

After all, we know that the two interbred, and a new study has attempted to explain how it happened. Conditions were best, the paper states, when the glaciers receded and warm weather allowed temperate forests to connect the species’ two worlds, which otherwise remained relatively separate.

The best-known product of Neanderthal-Denisovan hybridization is “Denny,” a 90,000-year-old fossil specimen that had a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother. Found at Denisova Cave in Siberia, Denny is evidence that interbreeding was widespread, as is our own Homo sapiens DNA, which contains short tracts from the other two early human species.

Illustration of Neanderthal (red) ...