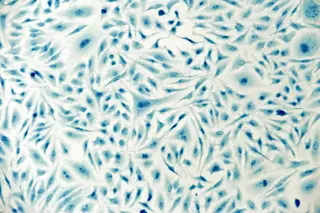

Angie Rojas's cells are about to be returned to her. Taken from her bone marrow five days earlier, genetically altered and nourished in the lab, the cells nestle in the tip of a syringe, about 45 million of them, a pale nib barely visible in the liquid. When the doctor nods and the nurse starts the "push," the cells trickle through an IV lock into the teenager's bloodstream. It is September 1, 2001, and gene therapy is mounting another try.

Patients with a form of severe combined immune deficiency disease (ADA-SCID) have a defect in a gene that is crucial to immune function. The diagram above outlines a recent gene therapy trial that could correct the condition: (1) extract defective cells from the bone marrow, (2) insert a virus bearing a healthy gene into the cells, and (3) inject the altered cells into the patient.

José Rojas gets up from ...