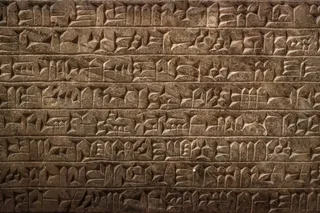

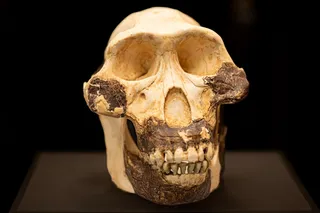

The desiccated skin and hair of mummies from the Nubian Desert reveal what ordinary Nubians ate a millennium or two ago. The Nubians were kings once: they built pyramids and temples, carved delicate statues and jewelry, controlled trade along the Nile, and for a century or so, beginning in the eighth century B.C., even ruled Egypt, their neighbor to the north. Mostly, though, the Nubians have been pawns, invaded by the Persians and Assyrians, dominated by the Egyptians -- and finally flooded. When the Aswân High Dam was completed in 1970, the reservoir it created inundated thousands of square miles of land along the banks of the Nile, from Egypt south into the Sudan. Nearly all of what was once the Lower Nubian heartland is now Lake Nasser. Before the flood, however, teams of archeologists from around the world flocked to the region, hurriedly salvaging what they could of the ...

What the Nubians Ate

Discover how the ancient Nubians’ diet reveals their agricultural practices and the mysteries of Meroitic Empire history.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe