Shortly after the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was formed in 1958, its engineers began visiting elementary schools in the leafy suburbs of Washington, D.C., to practice inspirational speeches in front of kids. The space program hadn't yet hardened into a race against the Soviets. It was still pictured as a journey of exploration, one that would eventually lead to colonizing first the moon, then Mars and the rest of the solar system. At least, that's the way Gregory Bennett remembers the message the NASA guys gave to his third-grade class.

From that day on, Bennett was wedded to the space program. The Mercury shots thrilled him. Gemini entranced him. But nothing beat Apollo. It wasn't just Neil Armstrong's "small step for man" or the Apollo 13 cliff-hanger. The missions opened up spectacular vistas of an alien world, culminating in 1972 with Eugene Cernan and Harrison "Jack" Schmitt's 18-mile, 22-hour jaunt throughout the breathtaking Taurus-Littrow Valley, just southeast of the Sea of Serenity, a 3.7-billion-year-old, 350-mile-wide lava-flooded valley.

But then Cernan and Schmitt parked their Apollo 17 rover, walked up the steps of their lunar module, sealed the door, and blasted off back to Earth. With the lack of atmosphere, it would have taken only a few minutes for the dust kicked up by their rocket exhaust to settle on the equipment they left behind. But once covered, it lay there undisturbed, a lunar version of Miss Havisham's wedding cake. It lies there still.

Over the passing decades, Bennett has grown into a man with thinning hair and a full beard and the gentle mien of a giant plush bear. Now he is in his late forties, and on a typical day he can be found in meetings at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston. The photo id hanging from his neck identifies him as an employee of Boeing, NASA's primary contractor for the International Space Station, where he is senior principal engineer for extravehicular activity (EVA) operations. In other words, when it comes to figuring out how astronauts are going to assemble the station, Bennett is the Man. He gives the impression of being one of those fortunate souls who gets paid for having fun. This good nature, however, masks a decades-long grudge.

"Apollo was worse than an anticlimax," he says. "It showed that space is nothing but a political football, which it always was. Building space colonies was never on NASA's shopping list." Bennett tries to propel these lines with vitriol, but he can't muster very much. He is not a bitter man. He loves his day job. And even though it does little to satisfy his longing for the moon, there's always his other identity to fall back on. On evenings and weekends, Bennett is one of the leaders of what you might call a lunar underground, a group called the Artemis Society, which is bent on circumventing the politics and bureaucracy of NASA and striking out on its own for the moon. Bennett probably knows more than anyone how this might be done; he has written hundreds, maybe thousands, of pages of plans, and he is the unlikely chief executive of a commercial company, Lunar Development Corporation, empowered to execute them. "I figure we can put a man on the moon for about $1.5 billion," he says matter-of-factly. After an awkward silence, he adds: "We're going to do it. We are going to the moon."

Bennett and his cohorts are not the only ones packing their bags. After decades of neglect, the moon is once again becoming an object of human enterprise. Suddenly, just about everybody, it seems, is trying to get there, including a motley collection of entrepreneurs and dreamers here in the United States.

Everyone, that is, except NASA. The only people who have ever gotten us to the moon have no interest in going back: they have their hands full with the space station, and their eyes cast in the direction of Mars. With NASA on the sidelines, and with no cold war in sight, those listening to Bennett's pitch could be forgiven for wondering how a new lunar program might be structured and who, in this day of budget cuts and belt-tightening, would be willing to pay for it. And why?

Wendell Mendell attended the Twenty-Ninth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference last March at the Johnson Space Center, as he has attended just about every moon conference since the mid-1960s, when he was a planetary scientist for the Apollo missions. Mendell, whose thin white beard makes him look like a wizened garden gnome, still works for JSC's Planetary Science Branch, and he is one of the leading advocates for putting people on the moon. He also knows firsthand how difficult it is to get the lunar bandwagon rolling.

Back in the early 1980s, Mendell and his colleagues spurred NASA-affiliated engineers and scientists to think about and plan a return mission to the moon. The result was the first Lunar Base Symposium in Washington, D.C., in 1984. Momentum flagged after the Challenger explosion in 1986 but picked up again in 1989 when President Bush made a Kennedyesque speech challenging NASA to go to Mars. NASA responded with a 30-year plan that used the space station and the moon as starting points. Unfortunately, the price tag-$500 billion to $600 billion-triggered the gag reflex in Congress.

But Mendell has quietly continued to plug the moon, writing articles such as "Lunar Base-Why Ask Why?" He wants to go not for national pride but for another equally old-fashioned reason: knowledge. The moon has much to teach us, he says, about the origins of the solar system. "Fifty years ago, if you looked at Lake Manicouagan in Quebec on a map and remarked that it was awfully round, scientists would have told you that it is a crypto-volcano-a volcano crater with no apparent volcano. In those days, everything was a volcano. Now we know it's an impact site-we understand that terrestrial processes are altered by the space environment. In this sense, the moon is a geologic time machine. It underwent some of the processes that Earth underwent, but then it just stopped. It is a record of the early days of the solar system, just waiting to be read."

So far scientists don't know much more than the broad outlines of that history. Even the moon's origin is far from being settled. Over the past 15 years, many have come to agree with the so-called Big Whack theory, which holds that about 4.5 billion years ago a rogue planet roughly three times the size of Mars collided with Earth. Most of the asteroid broke apart or vaporized and wound up being incorporated into Earth, while chunks of Earth vaporized, cooled, and coalesced into the moon. This would account for the moon's seemingly being made of the same material as Earth's mantle, why Earth and the moon spin about each other with more angular momentum than any other planet-moon system, and why the moon appears to have no iron-rich core. It also explains the relative dearth of lunar "volatiles"-materials, such as hydrogen, helium, and water, that have low boiling points and that a collision would have vaporized. But the Big Whack theory still has many loose ends that only a trip to the moon could tie up.

At NASA these days, however, Mendell and his colleagues are voices in the wilderness. When it comes to sending people to space, the moon is still pretty low on NASA's list of priorities-far below Mars, for example. But wouldn't the moon be a good place to practice getting to Mars? "On Mars, you'd need a technology that can go for three years without maintenance," says Mendell. "You need to develop a lot of know-how. And if you miss a launch, you have to wait 26 months for another. Sure, you can put people in Antarctica and pretend they're on Mars, but psychologically the moon is much better preparation, and psychology is important in determining how people can live in space."

John Connolly, an engineer in NASA's Exploration Office, doesn't rule out a trip to the moon. "Some people think we'll never get to Mars without first going to the moon," he says. "Others think it would just get in the way, sucking up money that should go toward getting us to our ultimate destination. I tend to be somewhere in the middle. But the scientific rationale for going back is not sufficient. Frankly, moon bases aren't even on our radar screen. We've looked into them, and you could design one, but the question is, why would you even want it? The only reason you'd want to go to the moon is to verify things you'd need to go to Mars."

Even if we could do it on a shoestring-say, for $1.5 billion, about 1 percent of what Apollo cost, adjusted for inflation-Connolly doesn't think it would fly at NASA. "There are very few things we'll spend a billion dollars on just because they're cool," he says.

A casual stroll through the meeting rooms at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference revealed a similar bias: lively, packed sessions devoted to the Mars Global Surveyor, to the meteorites that may or may not harbor signs of Martian life, and to images of Jupiter and its liquid moon Europa. The handful of sessions on the moon, by contrast, were sparsely attended and vaguely melancholy. After all, how excited can you get about new ways to interpret 25-year-old moon rocks? There was one glaring exception, though: the summary of data from the Lunar Prospector orbiter.

Back in January, only weeks before the conference convened, the probe had arrived in lunar orbit and started making detailed maps of the surface. The biggest jewel in a treasure trove of scientific data was the first incontrovertible evidence of water on the moon-about a billion tons of it, more even than moonstruck optimists had expected.

To be sure, water on the moon is a great scientific find and gives evidence of impacts by primordial water-bearing comets. A comet striking the moon would have vaporized, cooled, and settled onto the surface as frost. The sun's powerful rays would have evaporated most of it, except for a few deposits in deep craters at the poles, where steep walls would have blocked the almost horizontal sunlight.

But even scientists are more excited by the practical implications of water for future moon colonies. Not only is it essential for survival, but its constituent elements, hydrogen and oxygen, happen to make the most potent of rocket fuels.

Water on the moon has given the lunar underground a fillip. "Primarily, the existence of water opens people's minds to going to the moon," says Alan Binder. "It doesn't seem like such a foreign place. It's like finding gold. California could have been settled without the gold rush, but it sure helped."

Binder is a dapper, white-haired 58-year-old who usually wears a pinstripe suit, and for good reason. He has potential investors to impress. A planetary scientist turned entrepreneur, Binder was the driving force behind the scrappy, 650-pound Prospector orbiter, which, costing less than $63 million to design, build, launch, and maintain from the ground, definitely abides by NASA's "faster, better, cheaper" dictum. The orbiter itself is a model of thrift and modesty. It is small-it has only five instruments on it, short of the dozen or so needed to map the whole surface-but that made it easier to launch cheaply. "We could have done the job in one payload," says Binder, "but we decided to get it done in bits and pieces. So we'll need to send up three more payloads."

Binder had been trying to piece together private financing for Prospector, but when investors failed to materialize, he persuaded NASA to foot the bill. Now, after Prospector's resounding success, he hopes to raise private money for future moon-mapping missions. Binder is developing a new spacecraft that can accept an array of scientific instruments built by outside organizations-research firms or university scientists-even more readily than did Prospector, and without having to engage in the kind of engineering give-and-take that jacks up the cost of doing business with NASA. "The idea is that this thing is like a VW," he says. "We want to build them cheap and mass-produce them."

But what's the point of these missions? It couldn't just be the science, could it? Binder looks and sounds like a man who's out to make a buck, and he is able to sustain this impression for perhaps 15 minutes before he reveals more elaborate motivations. He is, to put it plainly, nuts about space. "You can't explore the moon without mapping it first," he says. "That's the first step. Once we've done that, we'll start working on sending landers-extremely simple landers, using only existing hardware." The next step is leaving things on the moon-equipment, robots, dwellings-and little by little build up lunar bases.

Eventually, Binder wants to start factories on the moon, churning out hydrogen or basalt bricks. He's not talking about a moon base now but a whole industrial infrastructure in space-the moon as industrial park. At present it costs about $2,000 a pound to launch a payload into low Earth orbit. If you're going to need goods in space, why not make them there? "Slowly but surely, you'd build up the capabilities to survive by yourself on the moon," Binder says. "And slowly but surely, the way our forefathers did in the New World, we'd build up an industrial capacity in space. The moon opens up the solar system. If you have industrial capacity to build from lunar materials, the moon could be a harbor. You could go there first, on your way to Mercury, Venus, or Mars."

Meanwhile, Binder has to get his fledgling enterprise off the ground. To do so, he must overcome a formidable obstacle. He has to convince investors that he'll be able to extract enough money from scientific institutions to make his venture work. That won't be easy. Scientists are notorious for having access to very little money. And would the NASA establishment-particularly the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which runs NASA's scientific missions-happily step aside while private firms muscled in on its territory? "JPL would squash you like a bug if you were a competitor to its feeding stream," says Mendell.

Mendell doubts that scientific arguments alone are ever going to get us back to the moon. In 2003 the Japanese plan to launch the first of a series of four lunar landers and an accompanying orbiter to make detailed maps of the moon's gravity field. But there's no saying when the subsequent missions will go up and what they'll do. And the prospect of sending people is remote. An insider says that manned missions may take another 20 years.

What's needed, Mendell thinks, is something to get people excited about space, something that bypasses reason and appeals directly to passion. What could excite the passion of a large, wealthy, democratic people with a lot of time on their hands?

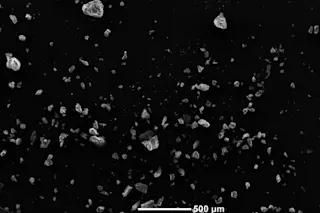

"There's a lot of talk about putting a five-kilometer-long optical interferometer on the moon," he says. An interferometer is a row of telescopes trained on the same object, so that when the images are combined in a certain way, they are able to resolve details much finer than any single telescope could. Scientists have long wanted to put an interferometer on the moon because the lunar surface, quiet except for vibrations from micrometeorites-tiny meteorites the size of sand grains-would provide a convenient, easy-to-service base. "You'd need to measure the impact of micrometeorites and compensate for them, and for that you'd need to put a seismometer on the moon, because measuring these vibrations is something you can't do now.

"And do you know how you could finance it?" Mendell pauses and leans forward, the better to deliver the punch line. "You could start a lottery based on what the seismic data for the day were going to be. If people will bet on a random number, why wouldn't they bet on the movement of a seismometer needle on the moon?" He's even thought up a name for his lunar lottery: he'd call it Lunar Powerball.

Mendell, of course, did not invent the idea of exploiting the moon for its entertainment value. Rather, it seems to be percolating up from some deep wellspring of common consciousness. Mendell got the idea for Lunar Powerball while talking with an executive from Shimizu, a big Japanese construction company with an interest in building in space. Somebody there was telling him about an idea to finance construction of a moon base by holding lunar bulldozer races, which would raise money from sponsors and television rights. Another executive from the same firm came to Mendell with an idea to put a camera on the moon to film Earth rising on the first day of the millennium. Mendell politely pointed out a small flaw: Earth doesn't rise on the moon. Since the moon doesn't rotate relative to Earth, Earth always stays fixed in the sky. Mendell informed the executive, however, that the moon has a slight wobble, which means that from the east or west limbs, Earth would periodically dip below the horizon and rise back up again. Of course, it takes one lunar day-29 Earth days-for Earth to dip and come up again, so it would all happen very slowly. Think of watching the sun setting 29 times slower.

But the lightbulb really went on when Mendell first heard about Celestis Corporation, the Houston-based company that launched Timothy Leary's ashes into orbit last year. "Funeral homes have these binder notebooks that clients look through, and there's a section near the back that talks about paying extra for, you know, putting your loved one's ashes at the eighteenth hole of his favorite golf course, or in the Andes Mountains, or whatever. Celestis made a package that slips right into the binder. They had to go through all the hoops to break into that business. It wasn't easy, but they did it. And they said they would make a profit after the first launch. They have had two. Now that's a business model."

The question is, who is going to do for the moon what Celestis did for ashes in orbit?

Denise Norris, a former computer-industry consultant turned entrepreneur, is chief executive officer of Applied Space Resources, a private firm she formed with the goal of putting together a lunar sample?return mission. The idea is to build a cheap lander, plunk it down in the Sea of Nectar, and bring back about 20 or 30 pounds of moon rocks. She'll sell more than half to scientific organizations for $3,000 to $5,000 per gram, but she'll put aside several pounds to sell as souvenirs. "I think we could get about $200 for a moon rock the size of a dried pea," she says.

Norris insists that the project wouldn't require any new technology; after all, the Soviet Union did a robotic sample return with their Luna landers back in the 1970s. The total cost of the project would be $50 million to $60 million, depending on the type of launcher used. And there may be commercial spin-offs. "We could take the landing simulator and make a game out of it. We could even have a contest to see who could do the best job on the simulator. The winner would get to watch the launch." Like a whole host of would-be lunar entertainment czars, she is currently trying to raise capital for the venture.

Then there's LunaCorp, a private firm cofounded by David Gump, the former publisher of a space-industry newsletter who got hooked on the idea of putting together a space mission. He wants William "Red" Whittaker, a roboticist at Carnegie Mellon, to build a moon rover with "telepresence," which would be controlled from Earth via joystick-preferably by an adolescent in an arcade in an amusement park somewhere. Thanks to high-bandwidth electronic communications technology, it would be your eyes and ears on the moon, going wherever you want it to go for as long as you want to pay for the privilege of operating it. "Using telepresence, we're getting more of a democratic approach," he says. "Millions of people could switch into the bodies of the robots." After nine years on the stump, Gump has succeeded in raising "a little bit of money."

Oddly enough, Europe almost boasted the first venture to squeeze entertainment out of the moon. It started in utter seriousness when Dutch astronaut Wubbo Ockels had an epiphany on the space shuttle Challenger in 1985. "You get in this machine and eight minutes later you are above the atmosphere," he says. "Earth looks so small and fragile. It looks like a park. And then it becomes perfectly obvious that you must do whatever you can to preserve it, and also to lessen your dependence on it."

Ockels spent seven years putting together an alliance of European commercial firms and the European Space Agency to send a lander to Aitken Basin on the moon's south pole. At 1,350 miles in diameter and 1.8 miles deep on average, it is one of the biggest craters in the solar system. There is a point where the west rim of the Shackleton crater, a smaller crater within the basin, intersects with the rims of two other craters, forming a peak about 4,000 feet above the basin floor. Ockels calls this "the peak of eternal light" because it is thought that the sun falls on this patch of ground day and night, virtually year-round. Solar panels placed on the peak could provide continuous power to a nearby moon base, which could use the power to mine ice deep within nearby craters.

Ockels wanted to start modestly by sending a small lander equipped with a video camera to celebrate the millennium. But last March, politicians denied the funding. "I was flabbergasted," he says. "I thought this plan was so fantastic. It really looked like it was snowballing."

Nobody thinks bigger than Greg Bennett, though, when it comes to mining the moon's entertainment resources. He and the other several hundred or so members of the Artemis Society have put together a plan that is all-American and very contemporary-and doesn't rely on wringing money from space-happy investors. "Look at it this way," he says. "Disney is bigger than NASA. Disney's annual profits are now bigger than the budget for the space-station program. When I realized that, it made me think we've been approaching space in the wrong way all along."

Before he even starts building a spaceship, he wants to get a revenue stream going. He's started Lunar Traders, a retail store that sells memorabilia about the Artemis Society's mission to the moon. He is also busy developing story treatments for movies and television. "Like a documentary about doing the Artemis project itself," he says, "or the lives of the people who'll be going to the moon." And then there's Artemis magazine, which will be about-you guessed it-the Artemis Society's efforts to reach the moon. The magazine will be launched soon, Bennett says assuringly. He spoke only the other day to the publisher, who's putting out the magazine from his apartment in Brooklyn, but "I wasn't able to pin him down." Once it's up and running, though, he'll sell it on the stock market, using the bounty to further the mission.

"When we get enough money coming in, then we'll build something," he says. "It's a very Disney-ish approach."

Bennett admits that it will be four or five years before he even begins designing a spaceship, and it'll be years more before it flies. A lot can happen in that time. If that day ever comes, however, it will have been worth waiting for. There'll be no grainy black-and-white television pictures, no mumbo jumbo about history in the making. If you think that Bennett is using tourism merely to jump-start a serious moon program, think again. In his vision, tourism is the sine qua non of the development of the moon, and the entire solar system for that matter.

Let's assume, for argument's sake, that the angels of the free market take a shine to Bennett. The year is 2012. After the inevitable fits and starts, Lunar Traders has made a killing in space memorabilia, Artemis magazine has surpassed Discover in circulation and has been sold for many tens of millions, and Bennett has opened an office in Hollywood, cutting deals left and right with movie producers desperate for footage to satisfy the public's insatiable appetite for moon flicks. Investors flock to Bennett for a piece of Artemis: The Movie. Finally he is free to build his spaceships. The launch date arrives. The cameras are rolling.

To keep his overhead low, Bennett first has his astronauts hitch a ride to the space station, either on the space shuttle or some other launcher, and then switch to a lunar transfer vehicle. This would consist of a Spacehab module-a type of small space lab built privately for NASA-modified to include rocket engines and a lunar lander. The lunar transfer vehicle takes the astronauts on the three-day journey from Earth orbit to lunar orbit and then remains there while they proceed down to the surface. No need for a command module pilot in this day of intelligent robots.

On the lunar surface, much work has already been done. Housing, in the form of three Spacehab modules, is already in place. A robot rover has been methodically burying the modules in regolith-lunar dirt-to protect them from the -240 degree lunar night, from the sun's harsh rays, and from the continuous barrage of micrometeorites. The robot pauses long enough to film the astronauts as they land.

It promises to be quite a sight. The three astronauts make the two-hour trip from lunar orbit down to the surface sprawled out on an open platform, like fish on a platter, with a rocket engine stuck on the bottom. "The flight would pose no greater hazard to the crew than two hours of surface EVA," Bennett writes. (Still, it's better than the version NASA's Connolly thought up back when the moon was still a plausible destination. He had the astronauts standing upright, hanging to straps for dear life.)

The first thing Bennett's astronauts do is check out the landing site, gather a few moon rocks-and turn on their camcorders. A high priority of business is to get stock footage for the inevitable documentaries and other entertainment vehicles that are financing the operation. Since the astronauts have already undergone rigorous training in acting school, they have no trouble enacting scripts for scenes in movies.

After that, Bennett's plans get a little dreamy. They start with lunar resorts: "Getting people up there would cost, oh, maybe $100,000 per person," Bennett says. "It'd be like a luxury capital tour of Europe. It's about what you'd spend to go to Mount Everest. If you had a resort on the northeast corner of Mare Crisium, there's a place called Angus Bay where you could go spelunking."

The real apple of his eye would be to discover one of the long lava caves that scientists believe may be commonplace. Of course, none of these lava tubes has been discovered. (That's probably because nobody's looked very hard. Only one Apollo mission took a deep core sample, and that went down only about three feet.) Rather, scientists infer their existence from rills-long, snaking valleys formed from lava flows, which presumably