Astronaut Megan McArthur in the suit-up facility about four hours from launch, 11 May 2009. Image by Michael Soluri, Infinite Worlds It’s a beautiful October morning in Houston, but I am grumpy and bleary-eyed as I make my way into Mission Control. I’ve just come off a string of Orbit 1 shifts (midnight to 0800) working as CAPCOM in the International Space Station Mission Control Center. (CAPCOM is the call sign for the astronaut on the ground who speaks to the crews that are in space.) Now I’ve slam-shifted back to daylight hours to work as CAPCOM during a simulation of the rendezvous planned for an upcoming shuttle mission. I see my friend Ray J in the parking lot, and he waves me over. Ray J is a pilot in the astronaut class ahead of mine. We’ve flown dozens of training flights together in the T-38, and he is a good friend and mentor. And he is always smiling, even at 0645. We chat for a minute, which mainly involves me complaining about my schedule, and then he asks, “So, have you talked to Scooter lately?” I raise my eyebrows at him. Scooter is way senior to me, a flown guy, a space shuttle commander. Of course I haven’t talked to Scooter. Scooter sometimes stops by the office I share with Mike Massimino because they flew on the last Hubble mission together, but it’s not like he’s coming there to shoot the breeze with me. So I say, “No. Why do you ask?” “Oh,” says Ray J nonchalantly, “I was just wondering how he’s doing.” That was weird, I think as I head into Mission Control. But then I forget all about it and spend the next ten hours working the simulation. That evening, as I’m propped up on the couch at home trying to stay awake until a reasonable bedtime, my phone rings. It’s Steve Lindsey, the chief of the Astronaut Office. This is definitely weird. Why is he calling me at home? This can’t be good. He says to me, “I’ve been trying to reach you, but you haven’t been at your desk for the last four days.” Feeling a little indignant, I mention that I’ve been living inside Mission Control all week. “Well,” he says, “how would you like to be the flight engineer and robotic arm operator for the final Hubble mission?” And then I just start laughing. Chalk it up to sleep deprivation, or maybe sheer giddiness at finally getting a flight assignment after six years in the Astronaut Office, but I couldn’t help it. Steve says, “I guess that’s a yes!” and proceeds to tell me who else is on the crew. Scooter is the commander, of course; Ray J is the pilot; Mike Massimino and John Grunsfeld are the two veteran spacewalkers; and two of my classmates, Drew Feustel and Mike Good, round out the spacewalking team. And then there is me, the last to know. But that’s okay—I’m not complaining! The next week NASA makes the big announcement. Our crew (now I’m on a crew!) gathers around the television in Scooter’s office to watch. Previously, the final servicing mission to the HST had been canceled, but now Mike Griffin, our NASA administrator at the time, details his reasons for adding the mission back to the flight manifest, and then proceeds to introduce the crew. He reads a brief but glowing bio for each crew member, but by the end he has run out of steam. “Megan McArthur will be the robotic arm operator and will, um, perform other tasks as needed.” Oh boy. Just call me “other tasks as needed.” But I’m still not complaining. Formerly an oceanographer, I am now the flight engineer and robotic arm operator on the final servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope—a telescope that has forever altered mankind’s view of the universe and our place within it. I am thrilled.

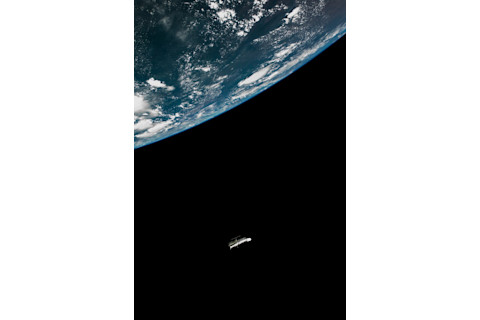

May 2009: Release of the Hubble for the last time from the cargo bay of a space shuttle. Image by John Grunsfeld/NASA from Michael Soluri’s Infinite Worlds. After all these years, training for an actual mission is incredible. And what a mission: launch in a space shuttle, rendezvous with another free-flying spacecraft in orbit around the Earth, grab that spacecraft and load it into the space shuttle’s payload bay, conduct five space walks in five days, let the spacecraft go, come home. I can hardly believe I get to be a part of all this. I can hardly believe I’m the one who has to capture the telescope! It’s not like I’m the first person to ever grab the Hubble. But it will still be the first time I’ve done it, right? Well, yes and no. A large part of my training is spent learning how to capture the HST in every scenario my instructor, Linda Snider, can imagine. The telescope attitude control might be broken, so the telescope is spinning rather than stable. The robotic arm might be partially broken, so it can only move a single joint at a time. So many things can go wrong, and I have to learn how to respond to all of them. The first time I sit down with Linda to grab the telescope, we use a desktop simulator. I break into a cold sweat and squeeze the hand controllers so hard it’s a wonder that I don’t crush them. When I finally get a capture, I look at Linda and say with a grimace, “Well, that was fun.” And she dryly replies, “And that’s as easy as it’s ever going to be.” Linda and I spend hundreds of hours in a simulator we call the Dome, where we simulate the rendezvous-and-capture portion of our flight. The Dome consists of a mock-up of the rear portion of the shuttle flight deck and a large curved screen (hence the name). As you look out the rear and overhead windows of the shuttle mock-up, you see an image projected onto the curved screen that represents what you would see out the real orbiter’s windows during flight. Think of the space shuttle as an extended-cab pickup truck. Take the backseats out of the cab and look out the rear windows into the bed of the truck and you’ll get an idea of the setup. By the time I get through eighteen months of training, I’ve captured hundreds of virtual Hubble Space Telescopes with the virtual robotic arm and placed them in the virtual bed of our space pickup truck. Telescope upside down or spinning, robotic arm busted—you name it, and thanks to Linda, I can do it. Now that it’s time to launch—at last!—I’m feeling pretty confident, or as confident as you ever want to feel before messing with a $10 billion piece of government hardware. But whenever a journalist asks me, “How do you think you’ll feel when it’s time to catch the telescope? Nervous? Excited?” in a preflight interview, my answer is always, “I have no idea.” There’s just no guessing how it will feel when the moment arrives. Anything can happen.

Megan McArthur. Image by Michael Soluri, Infinite Worlds It’s now the third day of the mission, and the moment of truth is upon me. In order to capture the Hubble, the space shuttle has to be in a very specific position relative to the telescope so that the robotic arm can reach the grapple fixture, a structure on the side of the telescope that allows us to grab hold of it. Throughout the day, Scooter and Ray J have been expertly maneuvering Atlantis into position. Near the very end of the rendezvous, due to a problem with ground commanding, we have to execute a final maneuver, a delicate pas de deux with the Hubble sitting 150 feet from the shuttle while both vehicles are moving at 17,500 miles per hour in orbit around the Earth. No problem. Scooter continues to fire jets to slow Atlantis down as we get closer and closer to the telescope. I am using the camera on the end of the robotic arm to tell him when I think the shuttle is in the right position. I know we have five space walks to conduct over the next five days. Drew, John, Bueno, and Mass will perform impossibly hard, never-before-attempted “brain surgery” on this one-of-a-kind telescope, a telescope that will help unlock the secrets of the universe. But first I have to grab it. As it turns out, I feel absolutely calm. Out the window, the telescope is—finally!—exactly where it is supposed to be. Scooter has flown a flawless approach. The robotic arm is in perfect working order. Thanks to my instructors, I know exactly what to do. So I do it. And then I exhale. And then I laugh. How do I feel? I feel good.

Text and images excerpted from Infinite Worlds: The People and Places of Space Exploration, by Michael Soluri. Used with permission.