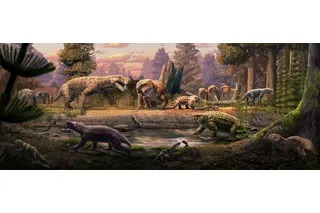

Dinosaurs roamed for thousands of years on Earth. They thrived in various environments, so they must have had some pretty good strategies for keeping offspring alive and ensuring the species' survival.

Learning about what these techniques might be hasn't been easy for paleontologists, who've primarily worked with scarce, fragmented fossil evidence.

The main theory is that just like living animals exhibit a variety of behaviors from species to species, it's likely that dinosaurs also were variable in their parenting. Some were neglectful and buried their eggs, while others caringly tended to their nest. And some lived alongside each other while others parted way soon after birth.

While paleontologists know more about dinosaurs and their lifestyles than you'd expect, it's been hard to collect solid evidence on the different parenting skills these ancient creatures could have had.

Much of what we know today relies on experts meticulously piecing together knowledge based ...