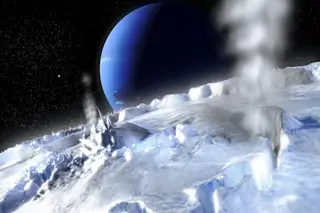

As a would-be Hollywood blockbuster, Pompeii is fizzling out. But when you watch the movie through the eyes of a volcanologist, things look quiet a bit different. "I thought, oh boy, another volcano movie. There’s already been Dante’s Peak, Volcano...but I was positively surprised. Actually, I was blown away," says Florian Schwandner of NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab. "Some of the effects that were used to show eruptive events in Pompeii were so realistic that I wasn’t sure if they used actual footage from eruptions of if it was animation. They got a lot of things very right, right enough that as a specialist I was excited seeing it."

The 79 AD eruption of Vesuvius, as envisioned in the movie Pompeii. (©2014 Constantin Film International GmbH and Impact Pictures (Pompeii) Inc.) To Schwandner, the real drama in Pompeii is not the love story or the swords-and-sandles battles, but the meticulous depiction ...