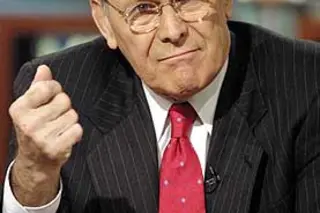

Dr. Free-Ride reminds us of the celebrated free-verse philosophizing of Donald Rumsfeld, from a 2002 Department of Defense news briefing.

As we know, There are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know There are known unknowns. That is to say We know there are some things We do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, The ones we don't know We don't know.

We tease our erstwhile Defense Secretary, but beneath the whimsical parallelisms, the quote actually makes perfect sense. In fact, I'll be using it in my talk later today on the nature of science. One of the distinguishing features of science, I will argue, is that we pretty much know which knowns are known. That is to say, it's obviously true that there are plenty of questions to which science does not know the answer, as well as some to which it ...