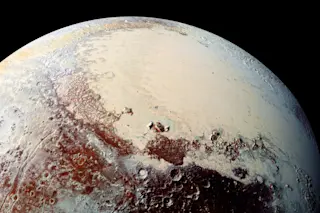

Pluto has left astronomers puzzled ever since the world was discovered in 1930. And its mysteries only grew in the aftermath of NASA’s New Horizons probe, which cruised by the dwarf planet in 2015. One point of confusion is Sputnik Planitia, part of the now-familiar heart-shaped region on Pluto’s northern hemisphere.

New Horizons’ instruments hinted that there might be an underground ocean in the region. Otherwise, the tiny, far-off world would be so cold it would have frozen through entirely. Yet Pluto’s crust in the same region is thinner in some areas than others, and that only makes sense if it’s frozen hard — warmer slush would spread out more evenly. Astronomers have been trying to explain those apparent contradictions ever since.

But now one group of researchers thinks they have an answer. The scientists say that a thin layer of insulation — gases like methane trapped inside an ice layer — might be the key to keeping Pluto both very cold and not quite frozen. The team of Japanese researchers led by Shunichi Kamata published their findings Monday in Nature Geoscience.

A Delicate Balance

The scientists suspect this insulating layer is made of a material called clathrate hydrates, which are gases trapped in a solid layer like ice. On Earth, we think of freezing oceans producing more or less normal water ice. But on Pluto, the oceans may have large amounts of dissolved gases and other substances. If the oceans produce a frozen top layer, it would include these gases, trapped inside the ice — and that substance wouldn’t act the same as normal ice.

This layer instead would have some unique properties that fit into the strange puzzle of Pluto’s ocean and ice layers. The layer is a good insulator — it doesn’t exchange much heat with the materials around it. And it’s viscous, supporting the slow movement of ice that leads to the strange differences in thickness scientists observed at Sputnik Planitia.

There are a few options for what kind of gas could be hidden inside this insulating layer. But one of the more likely suspects is methane, since Pluto and many bodies like it have plenty to spare.

Kamata and her colleagues came to their conclusions by using detailed modeling, and matching what their computer simulations predicted to what New Horizons has already revealed about Pluto. And Pluto isn’t the only cold world suspected to have underground oceans. So while New Horizons is long past Pluto now, scientists could still look for chances to observe this insulating layer in more detail.