Isachsen's quest began with a simple observation. He spreads a map out on the hood of his truck— a satellite image of New York State. "I first noticed this in the early 1970s," he says. "I had a grant from NASA to study features on this image. See all these squiggly lines? These are valleys formed by streams. That's what you'd expect a valley to look like. All squiggly, going in no particular direction. Now here's where we are. That's the valley formed by the Esopus Creek and its tributary, Woodland Creek. It forms an almost perfect circle around Panther Mountain. So I asked myself, what on Earth would account for that?"

Isachsen had a hunch that a meteorite had plunged into the site aeons ago; the circle might be a trace of the buried crater's rim. Although a few sites of such impacts were known in those days, most crater structures were presumed to have been formed by volcanic activity. Indeed, geologists once doubted that more than a handful of meteorites had ever reached Earth. What's more, they assumed that the sheer amount of geologic activity on Earth— everything from volcanoes to plate tectonics to the simple erosive forces of wind and water— would have wiped away any traces of impacts. In the early 1970s, however, images from the Apollo missions and other planetary probes had begun to put a new face on the geology of Earth and its near neighbors. Geologists were discovering that impact craters caused by asteroids, meteorites, and other forms of cosmic debris are the most common geologic features of the planets and their moons. Earth, they realized, would not have been spared.

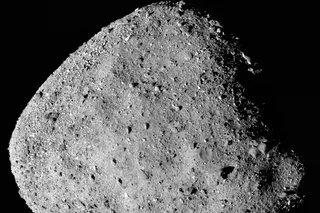

Closely spaced fractures in the bed of the Esopus Creek (left) in upstate New York helped feed Yngvar Isachsen's suspicion that a buried impact crater lay beneath Panther Mountain. He first grew curious about the site back in the 1970s when he noticed the creek's circular path on a satellite image (right). Such gloriously expansive views, Isachsen adds, have transformed the field of geology-and one of the results is a new understanding of the importance of impact craters to planetary geology. Isachsen has recently proven that the circular creek does indeed follow the rim of a buried impact crater.Photos by (left) Yngvar Isachsen; (right) landsat/Nasa

Isachsen initially lacked the resources to prove his hunch, but the notion that he might have a crater by the tail stirred his blood. Findings over the next few decades only strengthened his suspicion. "The science of impact craters is the new geology," says Isachsen. "We're finally realizing how important they are."

Cosmic collisions are now known to be a fundamental force not only in the formation of our solar system but also in the evolution of life-forms on Earth (see "Slamming Around the Sun," page 59). "Geologists are now finding craters like mad," says Isachsen, "because they're looking for them." Indeed, over the last 10 years meteorite hunters have found four or five new craters a year, bringing the earthly total to more than 160. Roughly one third of these craters are buried and— like the one Isachsen believes is buried beneath Panther Mountain— difficult to detect. And now, at age 80, Isachsen has finally pulled together all the evidence he needs to make his case.

Isachsen gathered his team together today to flesh out the dimensions of a site where, in a time before dinosaurs roamed the landscape, a meteorite or comet as much as one third of a mile in diameter blazed through the atmosphere and came crashing to Earth, releasing on impact the energy of 11 trillion tons of TNT.

Isachsen was a mere lad in his fifties when he identified the circle on the satellite map. Back then, he had his plate full as a researcher at the New York State Geological Survey, investigating myriad other, more pedestrian features of the Panther Mountain structure. Never very good at suppressing his curiosity, however, he stole time whenever he could to scout along Esopus Creek and Woodland Creek for telltale evidence of a buried crater.

If a meteorite had fallen on top of Panther Mountain, it would have been as distinct and easy to find as the three-quarter-mile-wide Barringer crater in Arizona, where anyone climbing along the ridge can peer down into its bowl-shaped depression. But given the lay of the land, Isachsen assumed that his suspected meteorite would have predated by tens of millions of years the formation of Panther Mountain— and all the Catskills for that matter.

Geologic formations indicate that the landscape during that era was a gentle, sloping plain. To the east, the Acadian Mountains, a spectacular range of snow-covered peaks, stood where the modest Appalachians are now. To the west, in present-day central and western New York State, lay a saltwater sea.

Isachsen surmised that rains running down from mountain to sea would have quickly turned a crater formed by a meteorite into a lake, then filled it with silt, and eventually buried the entire plain under a vast delta. Over time, the delta hardened into sedimentary rock. Had geology stopped there, any evidence of a crater would have been lost forever. But geology never stops. Rivulets and springs and creeks and streams and rivers carved valleys, which created the Catskill Mountains in relief. One of those creeks, the Esopus, ended up taking a circular path, ultimately carving a valley directly over the rim of the suspected buried crater.

If the creek was indeed following the rim of a crater, Isachsen expected he would find frequent cracks, or joints, in the rock of the creek bed. That's because rocky debris from the impact and subsequent sedimentary deposits settle more compactly inside the crater than around its rim. "What happens," says Isachsen, his hands emphasizing the steep drop of the crater walls, "is the layers of sedimentary rock that covered the crater tend to sag. And this sort of stretches the rock at the rim and causes it to crack." Sure enough, one day shortly after noticing the circular valley on the satellite image, Isachsen was poking around the Esopus Creek and hit pay dirt: joints in a rock outcropping at a particularly wide stretch of the Esopus. "It's not unusual for rocks to crack, of course, but typically this kind of rock will crack every three meters or so. The rock outcropping I found had joints 10 times more frequently— about every foot."

Isachsen's discovery was an important geologic quirk that fit his impact crater theory to a tee. Water, of course, takes the lowest pathway through rock. If there were an impact crater beneath Panther Mountain, Isachsen explains, the rock would break into smaller pieces precisely over the rim of the crater. And the waters that carved out the Catskill Mountains from the delta sediment would have naturally flowed over those paths where the rock breaks were smallest, forming the circular valley. "The rock wouldn't break like that," he says, "unless there was something going on beneath the surface."

This evidence certainly suggested there was an impact crater beneath Panther Mountain, but it by no means constituted proof.

At this point in the investigation, Isachsen's day job at the New York State Geological Survey began to get the better of his curiosity about Panther Mountain. For the next 15 years or so he was consumed with mapping unexplored areas of the Adirondack Mountains and writing books about the geology of the state. Then in 1993, at the tender age of 73, he finally began to complete this work and decided to give his attention once again to the Catskills site. He simply couldn't bear the thought of leaving the mystery unresolved.

When a meteorite slams into Earth, quartz in the ground melts along submicroscopic planes, leaving traces of melted and unmelted quartz that look like faint parallel lines. These traces are called shock lamellae (top). To find them, Isachsen's team spent hundreds of hours sorting through grains of quartz from the Panther Mountain site (bottom). "When you find a grain with shock lamellae," says Isachsen, "you're incredibly ecstatic."Photos by Yngvar Isachsen

Isachsen tried to learn more about the structure of Earth below Panther Mountain to see if he could recognize features of a crater. When a meteorite strikes, the walls of the resulting crater are too steep to support themselves, so after a moment they avalanche, pushing up a big mound of dirt and rock in the center. This mound, which is made up of fractured rock and pockets of trapped air, is considerably less dense than the rock that makes up the surrounding areas, which means it exerts a weaker pull of gravity. Isachsen thought he could measure this difference with a gravitometer. "These are sensitive instruments," he says. "If you put one on a tabletop and another on the floor, you'll get different readings because they're different distances from the center of Earth. So you have to be careful about knowing your exact elevation." He hiked up one side of the mountain and down another, taking measurements along the way. The data showed that there was indeed a volume of low-density rock directly beneath the peak of Panther Mountain— strongly suggesting the existence of a crater. But again, it wasn't proof.

What Isachsen needed was some direct geological evidence of the actual impact itself— something that only the unique physics of a meteorite impact could produce.

The impressive thing about a meteorite impact is not merely the amount of energy it unleashes. Earth holds a great deal more energy in its bowels but dissipates it over time in the form of earthquakes big and small and the occasional volcano. A meteorite impact, by contrast, is pretty much over and done in one brief second. It's a shooting star that makes it to Earth, its iron content tracing a bright streak of light as it burns up in the atmosphere. And it leaves lots of physical evidence for geologists to later sort through. Upon impact, a meteorite vaporizes, along with a good part of the ground beneath it, opening up a cavernous hole and spewing hot vapor for several miles in all directions. As air cools the vapor, droplets harden into tiny spherules and come raining down. Rock immediately below the crater melts and later hardens into a bowl-shaped sheet. The sudden shock also causes rock farther below to crack in a variety of very odd ways.

To unearth such evidence of an impact, Isachsen needed some way to gather rock samples from deep below Panther Mountain. A core sample would do it. Getting core samples involves drilling down thousands of feet and retrieving the intact rock from the hollow center of the drill bit, an exceedingly expensive operation. Oil companies routinely extract core samples when they're trying to find oil-soaked rock, but they can afford such attempts. Isachsen couldn't.

Searching through the literature, Isachsen found that a geologist named George Chadwick had taken an interest in the circular valley surrounding Panther Mountain back in the 1940s. Chadwick, though, attributed the shape to a dome— an area pushed up from below by some geologic force. In this case, Chadwick suspected it was natural gas. A firm called the Dome Oil Company had drilled a well into Panther Mountain and for a time was producing 50,000 cubic feet of gas a day— enough to power a farm, perhaps, but not a profitable business. "All these guys wanted to do was make a hole and see if they got gas," Isachsen says. "They didn't give a damn about the rock they went through." Nonetheless, the detritus of the failed project wound up in plastic bags— one bag every 10 feet for 6,000 feet of drilling#151; in collections at the New York State Geological Survey museum, where Isachsen eventually found them. These "cuttings"— consisting of finely ground rock— were not nearly as useful as intact core samples would have been, but the price was right.

Aided by a succession of graduate students in geology, Isachsen began going through each bag, grain by grain, looking for evidence.

When an iron-rich meteorite vaporizes on impact, the gases condense into a fiery rain of tiny iron droplets called spherules. Isachsen's team found a few spherules from Panther Mountain, such as the one shown here.Photo by Yngvar Isachsen

After a few years, they found some spherules half the size of a pinhead. Excited, Isachsen began preparing his case. He had the spherules photographed, then assembled the slides, wrote a paper, and presented his findings at a gathering of crater geologists in Budapest. He fully expected to have Panther Mountain duly recorded as a bona fide crater site. "This is where the whole scientific method comes into play," he says. "I thought I had evidence of a crater. But at the meeting, I tried this idea out on my peers, and they straightened me out. People there jumped all over me." A scientist in the audience asked Isachsen how he knew the spherules hadn't been deposited by a passing meteorite or a comet. Isachsen didn't have an answer.

"Finding spherules wasn't proof," he says, "but it gave me a reason to go on." The key, he decided, was to evaluate the rock samples in a more sophisticated way. He faithfully kept up his search through the rubble and began sending some of the grains to a small firm that separated out the quartz, set them in a clear block of plastic, and sliced the bits like deli meat so that they could be viewed under a microscope. Then Isachsen pored over the slices. Finally, in October of 1999, he found what he was looking for: shock lamellae, or microscopic imperfections in the quartz that can be introduced only by the enormous heat and shock of the meteorite impact. Quartz, after all, is a crystal, which means that its molecules are arranged in a regular formation, row upon row. Upon impact, the crystal can melt along submicroscopic planes, leaving traces of melted and unmelted quartz that look like faint parallel lines.

"Shock lamellae are regarded as evidence— proof positive— of a buried impact crater," says Isachsen. This time, however, he decided to be more cautious before presenting his case. He sent the slides to a group of academics in Canada, experts in impact craters, who confirmed the findings. Now Isachsen is writing a paper, which he will present once again to his peers. If everything holds up, the Panther Mountain crater will get the respect he thinks it deserves.

The motley crew Isachsen has gathered at Panther Mountain today, just about five months after he discovered the shock lamellae, has set the equipment to do underground soundings that will help him determine the shape and composition of the rock formations below. Three men in overalls and orange hard hats operate a drill from the back of their truck. A 10-foot-high drill bit slowly corkscrews into the ground. A fourth crew member stands ready to drop a stick of dynamite the size of a salami in this hole and detonate it, sending a small shock wave through the earth. If indeed a meteorite visited this spot, this shock wave will run smack into a layer of melted rock that once lined the bottom of the crater and bounce back up. Geologists will listen to the soundings with geophones— a half-mile-long string of microphones staked to the side of the mountain. The crew hopes to set off half a dozen blasts throughout the day.

High up the trail on the slopes of Panther Mountain, at the end of the string of geophones, there is no sound from the first detonation. At the appointed time, there is only silence. The data-recording instrument, hooked up to the geophones, registers a mess of squiggly lines. "Data!" shouts one of the geologists.

Isachsen, stationed near the blast site, is in a festive mood. One of the drillers floats the idea of coming back and taking some core samples down to 1,000 feet. Perhaps Isachsen and the other geologists might want to provide the equipment? Isachsen sounds interested but is noncommittal. He has thoughts of attracting the interest of commercial drillers, who might be able to do better than the Dome Oil Company in tapping natural resources beneath Panther Mountain.

Because of the way craters deform rock, Isachsen explains, they can be reservoirs of oil or natural gas. If the neighboring geology is right for forming hydrocarbons, the resulting oil or natural gas will seep through the fractured rock and collect beneath the crater. Perhaps a commercial outfit could be persuaded to take core samples down several thousand feet, to the crater floor.

But Isachsen is already moving on to other questions. "I suppose now that I've got proof there's a crater here, I should begin to figure out how big the crater is," he says. One uncertainty that remains is whether the buried crater was formed by a comet, which is made mostly of water, or an iron-rich meteorite.

At that moment, Isachsen is interrupted by the second underground blast. The sound, filtered through layers of geologic history, sounds much like the popping of a cork.

A few Web sites offer snapshots and maps of impact craters: gdcinfo.agg.emr.ca/toc.html?/crater/index.html and cass.jsc.nasa.gov/publications/slidesets/impacts.html.

The satellite image on pp. 52-53 was created by WorldSat International, a leading provider of cloud-free, natural color satellite imagery. Visit for more information.