Like every great comet, C/2012 S1 — better known to the world as Comet ISON — is dying. You could say the story of its demise began 14 months ago, when two observers near Kislovodsk, Russia, stumbled across a dim, fuzzy object while they scanned the sky near the constellations Cancer and Gemini. That fuzz was the outer layers of Comet ISON disintegrating and dispersing as it accelerated toward the warmth of the sun.

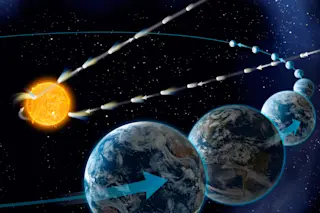

You could push further back and trace the comet’s downfall to a fateful event a few million years earlier. At the time, it was an inert chunk of ice, dust and frozen gases, floating nearly motionless in the outermost region of the solar system, a thousand times more distant than Pluto. Then some unknown disturbance, perhaps the nudge of a passing star, dislodged the comet from its stasis and sent it on a self-destructive sunward plunge.

...