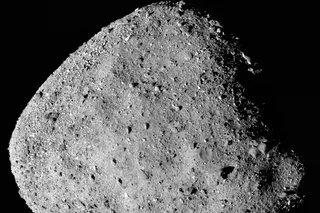

Two hundred million miles from Earth, just beyond the orbit of Mars, an odd object about twice the size of Manhattan tumbles end over end, revolving around the sun at average speeds of more than 40,000 miles per hour. Shaped like a lumpy, pockmarked potato, with an enormous crater at its middle— where, 4 billion years ago, it was almost riven in two— asteroid 433 Eros demands our attention for two reasons. First, it is one of the oldest objects in the solar system and therefore holds many clues about the earliest days of Earth. Second, it has 800 or so cousins nearby, one of which could someday put out the lights on our home planet.

Orbiting 62 miles above Eros, the NEAR probe caught this image of a 6-mile-wide, saddlelike depression at the asteroid's center.Photo by NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

Five years ago, as Congress voted to ...