Astronomers have caught sight of two stars that went kaboom only 2.5 billion years after our universe was created in the Big Bang, and say that ancient explosions are the oldest and most distant supernovas ever discovered. Researchers plan to use the new technique used to identify these supernovas to find other stars that blew up in the universe's early days, which may aid our understanding of how the universe was seeded with heavy elements.

Only a few lightweight elements – hydrogen, helium, and lithium – are thought to have been created in the big bang; all others were forged over time in the nuclear furnaces of stars and in supernovae. Since the spectrum of light from a supernova reveals the chemical composition of the exploding star, observing many such explosions would allow astronomers to trace out a chemical history of the universe [New Scientist].

Heavier metals eventually gathered in the clouds of dust that surrounded young stars, and sometimes formed parts of rocky planets like Earth. The study, published in Nature, reveals two Type IIn supernovas, which result from the explosive destruction of stars that are 50 to 100 times the mass of the sun.

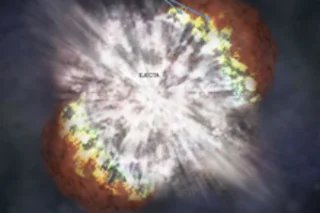

As they near death, the stars shed layers of material into space, creating shells around themselves. "When they explode, all the material comes screaming outside of the center and it hits that shell," [lead researcher Jeff] Cooke said. This action heats up the shell, causing it to glow brightly for years afterward [National Geographic News].

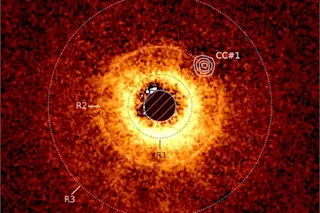

That long-lasting cloud of glowing gas is what allowed researchers to detect the explosions at a distance of 11 billion light-years. The researchers used data from a telescope perched on the top of Mauna Kea in Hawaii, which had recorded the same patches of sky for five years. In a process that mimics the effect of leaving a camera's shutter open for a long time to collect more light, the researchers blended all the information from each year's observations together, and then compared the data from each year.

"What we're looking for are things that were there one year, but which weren't there the next," explained [study coauthor Mark] Sullivan. "You see an image of the galaxy in which a supernovae exploded. When you subtract the two years' data, the galaxy disappears, because it hasn't changed. So you're just left with things that have changed - in this case that's the supernovae" [BBC News].

Related Content: 80beats: Just After the Big Bang, a Star Factory Went Gangbusters 80beats: Scientists May Have Detected the Death Throes of the Universe’s First Stars 80beats: The First Stars Started Small, Grew Fast, and Died Young DISCOVER: The Man Who Made Stars and Planets DISCOVER: In the Nursery of the Stars Image: M. Weiss/NASA/CXC