While the moon moves through its phases and the planets dance across the celestial stage, the backdrop remains stubbornly unchanged. The endless sameness of the stars is comforting but, let's face it, a bit dull. Imagine how much more exciting backyard astronomy would be if each night brought a fresh, slightly different view.

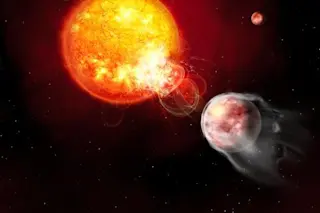

Actually, you don't need to imagine. Change is all around if you know where to look. Start with the bright red star Betelgeuse in the right shoulder of Orion, rising in the east a couple of hours after sunset. Compare it to Rigel, the prominent blue star marking Orion's left foot. Sometimes Betelgeuse is nearly as brilliant as its rival; most often it is fainter, as little as one-third as bright. You are witnessing the irregular heartbeat of an aging, bloated star. Over weeks to years, Betelgeuse's distended atmosphere shrinks, heats up, billows outward, cools, and falls ...