More than 4,000 years ago, an Egyptian named Dedi walked into the court of King Cheops and entertained the monarch and his subjects by decapitating oxen and geese and then reaffixing their heads, restoring the sorry creatures to vibrant life. How did he do it?

Dedi didn't reveal his secret, but anthropologist Diane Perlov is sure she knows. "All magic is based on scientific principles," she says. "Yet most people don't connect science with magic." The connection goes even deeper: Both performing artists and practicing scientists are motivated by a sense of wonder at the world's essential mystery. "Magicians capture that wonder, while scientists try to explain it," Perlov says. "But neither loses the appreciation that got them started in the first place."

Museum goers get a chance to lose their heads at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. The nifty optical illusion relies on the precise placement of a single mirror. Photo by California Science Center

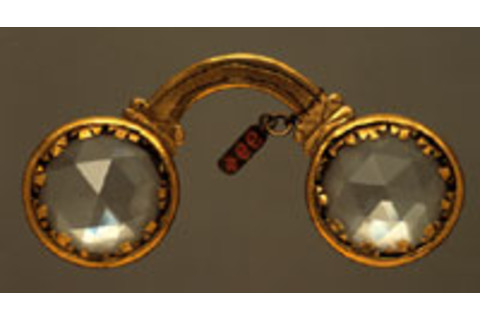

That shared fascination is on view in Magic: The Science of Illusion, an engaging new exhibit at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. Perlov, the show's curator, has assembled films and artifacts of famed performers, including the handcuffs and milk can Houdini used in his dazzling escapes. Even better, Perlov has enlisted the help of some of today's master magicians to create unique illusions visitors can then duplicate. In one of the most intriguing, the Amazing Living Head by the offbeat comic duo Penn & Teller, Penn recounts how Teller has suffered a horrific car crash that has left his head separated from his body.

A video monitor displays Teller's live disembodied head on a futuristic-looking stainless steel platform. Next to the screen is a small stage set visitors can enter to create the illusion that they, too, have lost their heads. Teller (always silent on stage) later explains that the trick is based on the simple optical principle that the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. That is, light bounces off a mirror at the same angle at which it arrives. "If you understand that," he says, "it's not hard to create illusions like these."

Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once opined that "any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." Indeed, for centuries magicians have employed the latest technology in their art. In the Light and Heavy Chest, modern magician Jade first performs on tape an illusion invented by Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, the 19th-century Frenchman who is considered the father of modern conjuring. Then Jade's recorded voice asks a museum visitor to lift a chest and set it down. No problem. Moments later, after following instructions to lean on two targets, the same person tries again and fails.

The explanation: The visitor has unknowingly switched on a powerful hidden electromagnet that locks onto a metal plate in the lining of the chest. In the 1850s, Robert-Houdin easily astounded a public that wasn't well informed about new technology like the electromagnet. That isn't the case today. "When you can sit on an airplane and somebody next to you is demonstrating the latest gadget," says Teller, "it's very hard to amaze people on the technological front."

Some performers, of course, don't depend on devices at all. In the Magic of Mind, Max Maven divines which of several shapes a person is thinking of— a crescent? A triangle? The mentalist's secret: mathematics.

When Maven asks the volunteer a series of questions, he's using a binary sorting program, in the way a computer uses mathematical patterns to run a search program. That doesn't explain, though, how in a live performance Maven can correctly guess that an audience volunteer has spent time at a remote village in Fiji. "One of the values of magic to science and society," says Maven, "is to remind us we're surrounded by mysteries." And that might be the best trick of all.

Magic: The Science of Illusion will be at the California Science Center through February. It travels to Philadelphia April 1 and Fort Worth next October; the exhibit will tour the United States through 2007. For information, call 323-SCIENCE or surf to www.casciencectr.org.

Television

Building Big A PBS miniseries produced by WGBH Science Unit, Boston, and Production Group Inc. of Washington, D.C. First episode airs October 3; check your local listings for times.

Every day, millions of travelers cross bridges like the Golden Gate, the Brooklyn, and the 2,050-year-old Ponte Fabricio in Rome without giving much thought to what holds them up. Other millions blithely traverse tunnels, live below dams, sit under stone domes, and ascend skyscrapers in perfect trust. But it wasn't always so, as this five-part series illustrates.

An intricate web of steel trusses supports the Houston Astrodome. Photo by The Astrodomain Complex

Indeed, much safety now rests on foundations created from the rubble of failures, explains David Macaulay, series host and author of the companion book Building Big (Houghton Mifflin, $30). For example, attempts to tunnel under the Thames River met with crushing defeat until 1824, when French engineer Marc Brunel took inspiration from a helmet-headed worm that bores into ships. He decided to try a similar shield to hold dirt walls in place as workers dug their way forward.

Brunel's tunnel collapsed twice before he got it right, but it survives to this day as part of the London Underground, and the concept is incorporated into modern tunnel-boring machines. Similarly, the 1879 collapse of a post-and-beam railroad bridge in Scotland led engineers John Fowler and Benjamin Baker to rethink lengthy spans in windy areas. They came up with the cantilever bridge, in which towers anchor a series of trusses that extend out like diving boards to suspend a railway or road. To show nervous spectators the design could be trusted, Baker perched on a narrow board supported by two assistants acting as towers.

As disparate as dams and domes and other gigantic structures may seem, many share a basic construction element: the arch. To demonstrate its effectiveness, Macaulay uses an animated cartoon of an elephant jumping up and down on a simple arc of stones. Soon the rocks pop out sideways. But when the arc is covered with layers of stones, the added weight compresses the structure, making it stable and impervious to even the most determined pachyderm.

That principle is hardly new. Ancient Romans built bridges, aqueducts, and domes using the idea, Gustave Eiffel applied the concept when he built his famous tower, and Hoover Dam is really just a sideways arch that uses water as the compressive force. But without a clever series like Building Big, one might never notice the marvels of engineering in everyday life, and knowing those principles makes crossing a bridge a much more engaging experience. — Fenella Saunders

In 1890, British engineer Benjamin Baker (center) demonstrated how a cantilever bridge design works. Photos by The Institution of Civil Engineers

Books

Valley of the Golden Mummies Zahi Hawass Abrams, $49.50.Conversations with Mummies: New Light on the Lives of Ancient Egyptians Rosalie David and Rick Archbold William Morrow, $40.

Every month brings beautiful new books on ancient Egypt, but these two are exceptional finds. Particularly welcome is Zahi Hawass's lyrical account of excavations in the Valley of the Golden Mummies. So much of what we know about the lives of early Egyptians has been filtered through Western scientists. Hawass provides not only the perspective of an archaeologist— he is director general of the Giza Pyramids and field director of the Bahariya Oasis excavation— but also that of a native steeped in the land and the culture. His evocative narrative weaves together stories of the upper-middle-class families buried in the Valley with tales of modern Egyptians who dwell in the villages nearby.

Equally compelling is Hawass's recall of everyday life at a dig, its sights, sounds, and smells (a newly unearthed mummy gives off an overwhelming stench). In a story worthy of a late-night movie, Hawass tells of being woken from sleep by images of two children. He recognized the faces as belonging to the boy and girl mummies that had been removed to a nearby museum. After weeks of sweat-drenched awakenings, he concluded that the children could not rest because they had been separated from their father. As soon as Hawass placed the father's mummy beside the children's, the hauntings ceased.

Less mystical but just as absorbing is Rosalie David's book. The director of the Egyptian Mummy Research Project at England's Manchester Museum offers fascinating history (mummy unwrappings were a frequent highlight of country weekends among the Victorians) and observations (every mummy has a unique scent) that museum visitors are not likely to come across on their own. But she is most interested in what can be learned about ancient Egyptians' health, habits, and living conditions from their physical remains. With science writer Rick Archbold, she details how researchers use the tools of modern science, from CAT scans to DNA analysis, to extract answers from their silent subjects. The process is so intimate, says David, that "after a while one begins to feel as though one knows each of them personally." — Rabiya S. Tuma

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition Houghton Mifflin, $60.

If you're still doubting the pace of technological change and scientific discovery, check out the latest edition of this workhorse dictionary. Of 10,000 words added since the last revision eight years ago, nearly a third relate to the sciences. Thumbing through the tome's 2,074 pages, you'll find new entries in virtually every field, from archaeology to zoology. Some of the new listings are bound to be familiar, like Viagra and greenhouse gas. Others are sure to startle. Try sonoluminescence and seaborgium, for starters. And did you know that rutherfordium, an artificially produced radioactive element, is also called unnilquadium? This dictionary even offers the lowdown on its isotopes and half-lives. Such a rich trove of new learning is sure to occupy you for many, many yoctoseconds.— Eric Powell

Free For All: How Linux and the Free Software Movement Undercut the High-Tech Titans Peter Wayner HarperCollins, $26.

To techie adherents of the open-source movement, free software is a way of life. For the rest of us, Wayner, a computer scientist and journalist, has charted the history of hackers who devote their spare time to writing code they make available to anyone free of charge. Their efforts, he insists, will soon change computing forever.

A Rum Affair: A True Story of Botanical Fraud Karl Sabbagh Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $24.

In the 1940s, respected professor John Heslop Harrison astonished British botanists with his discovery of nonnative grasses on Scotland's Isle of Rum. John Raven, a young Cambridge don, challenged the findings and eventually proved that Harrison had smuggled the grasses onto the island. A poignant and sometimes comic tale of out-of-control ambition.

E=mc^2: A Biography of the World's Most Famous Equation David Bodanis

Walker & Company, $24.

"The equation that changed everything" is familiar to even the most physics-challenged, but it remains a fuzzy abstraction to most. Science writer Bodanis makes it a lot more clear. He straightforwardly explains the meanings of E, m, and c^2, then leads us through the steps Einstein took in arriving at his formulation, and finally chronicles where the equation has taken the world.

The Two-Headed Boy and Other Medical Marvels Jan Bondeson Cornell University Press, $29.95.

English physician Bondeson uses centuries-old medical records, engravings, and paintings to sensitively document the lives of some of nature's strangest creations, among them hog-faced women, dog-faced boys, and horned humans.

Laughter: A Scientific Investigation Robert R. Provine Viking Publishing, $24.95.

Why do we laugh? Neurobiologist Provine provides some answers but cautions that there will probably never be a Grand Unified Theory of Laughter. A highly entertaining— if not laugh-out- loud funny— read.

Leonardo da Vinci Sherwin B. Nuland Viking Penguin, $19.95.

Leonardo: The First Scientist Michael White St. Martin's Press, $27.95.

Two new books argue that Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential Renaissance man, was a scientist first and an artist second. Nuland, a gifted essayist and surgeon, explores Leonardo's remarkable career as an anatomist. Journalist and scientific historian White links the details of the genius's life to his extraordinary career as an inventor. Both books benefit from reproductions of Leonardo's rich anatomic illustrations, which testify that he wasn't such a bad artist either.

Rube Goldberg: Inventions! Maynard Frank Wolfe Simon & Schuster, $25.

In the first half of the 20th century, newspaper cartoonist Goldberg's fantastic inventions were often more famous than most actual innovations. This compilation of more than 100 of Goldberg's most hilarious and sly cartoons will appeal to the secret Luddite in everyone.

Stardust: Supernovae and Life— The Cosmic Connection John Gribbin with Mary Gribbin Yale University Press, $24.95.

Current theory holds that all of Earth's matter, except for hydrogen, was formed in the crucibles of supernovas. Astrophysicist John Gribbin and science writer Mary Gribbin use elegant and precise language to explain that we are literally made of the same stuff as stars.

Blaze: The Forensics of Fire Nicholas Faith St. Martin's Press, $23.95.

Journalist Faith revisits some of the past century's most catastrophic blazes, including those at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York and the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas, to give a gritty account of how investigators use everything from old-fashioned detective work to computer modeling to zero in on the causes of fire.

Exploring Native North America David Hurst Thomas Oxford University Press, $39.95.

Using photographs, maps, and site plans, archaeologist Thomas gracefully reconstructs the scientific and technological achievements as well as the art, religion, and trade of early Native American inhabitants of 18 sites across the United States and Canada. -- Compiled by Eric Powell

For more about Zahi Hawass and his work, surf to guardians.net/hawass/index.htm. for details on the Manchester mummy Project, see www.museum.man.ac.uk/collections/egyptology/egyptology_research.html.