In 2018, when the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) opens its enormous eye on the universe and begins collecting data, the astronomers who envisioned it and the engineers who designed and built it will celebrate and cheer.

But even as the first waves of data beam down to Earth, another team of scientists will be hard at work designing its replacement. In fact, they have already begun.

Conceiving of, researching, and building science’s biggest, most valuable tools of inquiry — the Large Hadron Collider, or the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes — requires dozens of years, hundreds of expert panels and team meetings, and billions of dollars, and the gears that march these projects through the bureaucratic assembly line turn slowly. So it should come as no surprise that, while it won’t fly until at least the mid-2030s, astronomers are already planning the next next large space observatory, currently known as the High Definition Space Telescope (HDST).

Since the moment Hubble left the launchpad, different groups have discussed what this future project might look like, but they all agree on the basic requirements and objectives. “There’s not a million ways to do it,” says Sara Seager, astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She was also a co-chair for the committee tasked by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) to define a vision for HDST. “You have your science drivers and your engineering constraints, and you try to find a happy medium among all of those.”

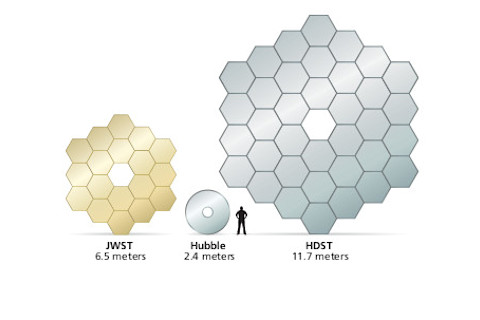

So, balanced between technologies within reach and the most pressing astrophysics questions of the day, the basics are already apparent to Seager and her fellow visionaries. While JWST will focus specifically on the infrared portion of the spectrum, HDST will be a true Hubble successor, with capabilities in the infrared, optical, and ultraviolet. JWST’s 6.5-meter mirror already dwarfs Hubble’s comparatively modest 2.4 meters, but HDST will span about 12 meters, matching the largest telescopes currently on Earth. And while earthbound telescopes will have advanced to 30 meters by HDST’s era, the space telescope will, like JWST before it, fly not just in space, but at the distant L2 Lagrange point, well beyond the moon’s orbit. It will command an uninterrupted and unclouded view of the heavens, far from Earth’s atmosphere or its photobombing bulk. From this pristine vantage point, it will peer into the farthest reaches of the cosmos and hunt the holy grail of astronomy: another living Earth.

The Search for Life

In 1995, exoplanets catapulted from science fiction to cutting-edge science when Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz discovered the first one orbiting a solar-type star. Over the next decade, searches from both the ground and space revealed a handful more, then dozens. In 2009, the Kepler spacecraft opened the floodgates, and hundreds and then thousands of exoplanets poured onto the scene.

But astronomers know only the slimmest of details for most of these planets. They know a planet’s mass or its size — they know both only in serendipitous cases — and the distance between it and the star it orbits. Determining a planet’s composition from this information is an exercise in intelligent guesswork, modeling, and puzzle solving. Even now, scientists have directly observed a handful of specific molecules that comprise a planet’s atmosphere in only a few dozen systems, and those are the brightest, hottest giant planets that hold no hope of life.

Far from being clinically detached, many astronomers dream of finding another Earth. They want to find life. It should be no surprise that some of the leading exoplanet researchers — among them Seager and Bill Borucki, who designed and headed Kepler — describe their motivations along these lines. “I think all of humankind is interested in our place in the galaxy, in life, in the universe,” Borucki says. “And the answer to that lies along finding intelligence, finding life, and finding planets on which this life could exist.”

These are very distinct tasks. Astronomers know of a handful of planets already where life could be present. These planets are the right size to have rocky surfaces, and they orbit in the habitable zone of their star where liquid water could potentially exist. Yet astronomers cannot ascertain whether water is actually present. And even if water is present — is life?

Answering this question means moving beyond a planet’s size and peering deep into its gas shroud to find the telltale signs of a living atmosphere: water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, methane, ozone. Only the interplay of such substances can reliably inform astronomers about the actual presence of life, instead of its mere potential.

Transit studies are the current best method for learning the components of an exoplanet’s atmosphere. Astronomers watch a host star as its planet crosses in front and measure how the observed starlight changes as the planet’s atmosphere blocks and filters it. This method yields rich information when the planet is large, puffy, and hot, like a Jupiter or Neptune on a tight orbit. But for a planet with Earth’s comparatively small size, compressed atmosphere, and more distant orbit, the change in light is simply too small to measure, even for future giant telescopes.

JWST will perform spectacular transit observations with so-called super-Earths, planets one and a half to twice Earth’s radius. But these planets are not especially Earth-like. So unless astronomers are lucky enough to find an extremely nearby Earth-sized planet with a cool M-dwarf host star, neither JWST nor any of the accompanying and upcoming fleet of exoplanet missions will have the ability to characterize a true Earth twin in the habitable zone.

The High Definition Space Telescope will be nearly twice the diameter of the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope. It already dwarfs Hubble, which remains for now the premier in optical observing. (Credit: Aura)

Aura

“Even around an M-dwarf star, the time required to perform a full spectroscopic measurement of a transiting Earth-sized exoplanet with JWST would be similar to that used for the Hubble Deep Field,” observes Marc Postman from the Space Telescope Science Institute, another member of the AURA team. And while E.T. might be worth 100-plus hours of telescope time, astronomers face reasonable odds that after such an investment, the planet might turn out to be a barren and arid exo-Mars instead of an exo-Earth. It is not a feasible way to conduct a large-scale study. Astronomers need a different tool — and so HDST was born.

Instead of using transits, Earth-twin investigators will look for the planets directly, a feat that carries its own stiff engineering requirements. They’re within reach, but they represent the most pressing challenges for HDST.

Strong science requires repeatability; Earth-twin hunters need a whole sample of potential Earths to study. Seager poses the question: “How many Earth-like exoplanet atmospheres do you think you need to get a handle on what’s really going on, including the search for life? Do you think it’s one? 10? 100? 1,000?”

She settles on “dozens.” It isn’t an abstract thought experiment. HDST will be exactly as powerful as is needed to answer the questions astronomers pose. Exceeding these specifications wastes precious budget dollars and can lead to impossible engineering demands. Underperformance would leave astronomers’ questions unanswered. And Seager has not just a question, but a mission: find the next Earth.

The James Webb Space Telescope team stands in front of a full-size model at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, where it is being assembled. The Webb is roughly the size of a tennis court when its sunshield is fully extended, and the High Definition Space Telescope will be almost twice as large. (Credit: NASA/GSFC)

NASA/GSFC

Stellar Archaeology

But HDST will be a telescope for the whole astrophysics community. Postman studies the formation and evolution of galaxies and large-scale structure in the universe, and he looks forward to HDST’s capabilities on these much grander scales.

“Where do galaxies get the gas to make their stars?” he asks. “We only understand that at a rudimentary level.” To make stars, galaxies must capture gas from the intergalactic medium. And energetic activities like bursts of star formation that form young and violent stars, as well as black hole evolution, can in turn spew gas back out of galaxies. Astronomers have many models of this cycle, but Postman says none of them has been verified at the detailed level they desire.

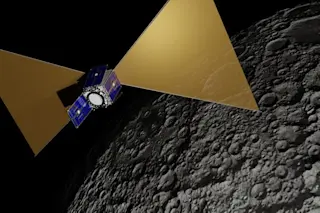

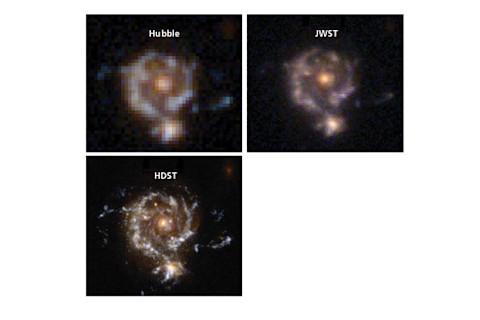

Modelers compare the resolution of a distant galaxy achieved by the High Definition Space Telescope (HDST), James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and Hubble. Only HDST is able to clearly pick out bright star-forming regions from older red stellar populations. (Credit: L. Pueyo & M. N’Diaye)

L. Pueyo & M. N’Diaye

Currently, Hubble tracks the position and motion of gas around galaxies by studying how their gas absorbs light from faraway quasars — bright pinpricks of light caused by active, much more distant galaxies far in the background. But Hubble usually can observe only one quasar per intervening galaxy, and that only in a small number of targets. “But if you had a telescope in the 10-meter class,” Postman says, “there would be 10 to 20 quasars behind every galaxy out to 10 megaparsecs [32.6 million light-years] that would be bright enough to pursue for these studies.” This would allow astronomers to draw spatially resolved maps of the gas around these galaxies. “That’s a game changer,” Postman declares.

Astronomers also are interested in so-called stellar archaeology, the history of star formation in galaxies. How many stars of every size did galaxies form, and how long ago? Again, Hubble attempts these measurements now, but has the angular resolution to study only the Milky Way and our closest neighbors in the Local Group of galaxies. HDST could map star formation out to the same 10-Mpc-range. And if researchers can understand the flow of gas that feeds star formation, these maps would be even more informative, painting a fuller picture of the history of the local universe and beyond.

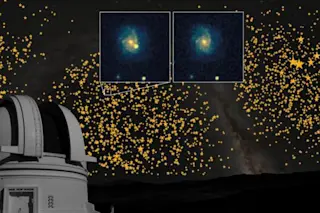

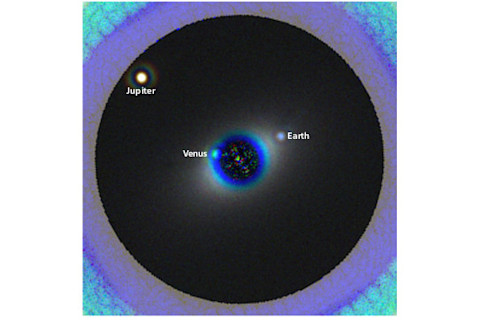

Astronomers model how the solar system would appear to an observatory the expected size of the High Definition Space Telescope with an internal coronagraph to block out a central star’s light. An Earth twin and its blue color could be detected with 40 hours of observing time. (Credit: D. Ceverino, C. Moody & G. Snyder)

D. Ceverino, C. Moody & G. Snyder

The upcoming generation of 30-meter-class ground-based telescopes will join in this search, but their best angular resolution comes in the near infrared, where the color differences between old and young stellar populations are far less dramatic than in the ultraviolet range HDST will access.

This difference highlights the complementary nature of the upcoming generation of telescopes. HDST will achieve its highest resolution in the ultraviolet, with the 30-meter telescopes matching it in the infrared. With its enormous team of networked dishes, the ALMA radio observatory can supply the same level of detail in its target range. Together, they will offer the most comprehensive maps of the nearby universe ever seen, delivering unprecedented resolution at the same spatial scale from radio to ultraviolet wavelengths. “It will be revolutionary,” Postman predicts.

The Build

Fortunately, astronomers are in agreement about what it will take for HDST to meet these various science goals, which informed their decision to build a 10-meter-class mirror (the exact size has yet to be determined) and fly it at L2. While engineers are already breaking ground to build telescopes three times that size on Earth, a very simple problem caps the size of any space telescope: There must be a way to get it into space to begin with. The largest vehicle planned for the foreseeable future is NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) Block 2, and even this leviathan rocket — nearly 400 feet (120m) tall and with a payload capacity of 150 tons — is only 8 meters across on the inside. This means that HDST, like JWST before it, must accommodate a foldable, segmented mirror design, with as many as 54 hexagonal pieces. It will blast off Earth folded onto itself in the belly of the largest rocket ever built, and unfold only when it reaches deep space.

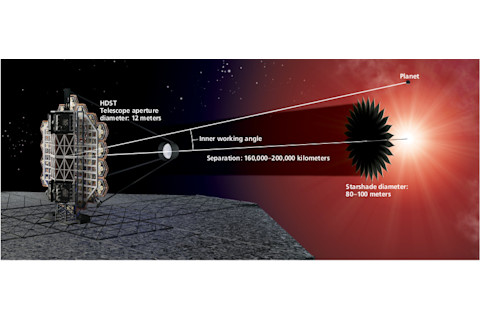

A starshade is a separate unit from the telescope that flies in formation far from its partner observatory. It blocks out light directly surrounding the star, creating a totally dark “inner working angle,” but allows the telescope to see much closer in than without the shade, when starlight glares too brightly to see planets orbiting nearby. (Credit: Don Dixon & Roen Kelly/Discover)

Don Dixon & Roen Kelly/Discover

Getting it to space is only one of the engineering demands. To find those elusive habitable exoplanets, scientists must reach beyond transits to direct imaging. But Earth, for example, is 10 billion times fainter than the sun, and from a distance of tens of trillions of miles away or farther, it would be lost in our sun’s glare. Astronomers need to kill the starlight.

Observers know of two ways to block out a central star’s light. The first uses a device known as a coronagraph, which sits inside the telescope and carefully obscures light from the star while letting through light immediately around it. This delicate operation requires an exceedingly well-engineered and very stable telescope where the path of light traveling through the spacecraft is perfectly understood and meticulously mapped, with components correcting the mirror’s shape to keep images stabilized against even the tiniest aberrations. It substantially complicates the overall telescope design, but the depth and clarity of the resulting images would yield thousands of planets and dozens of exo-Earths.

But there’s another way. For years, astronomers have dreamed of a starshade, an external version of the coronagraph with a delicate and complicated petal structure designed to perfectly eliminate the multispiked “diffraction” pattern of light cast by a faraway star.

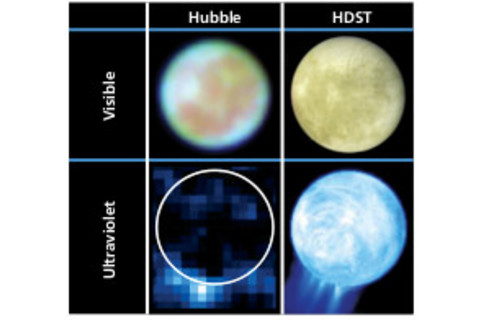

Hubble’s current view of outer solar system worlds, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa, provides the impetus for sending probes flying to the gas giants. But the High Definition Space Telescope could yield rich detail from its orbit near Earth. (Credit: Aura)

Aura

For a telescope the size of HDST, a starshade would be over 300 feet (100m) across and require that each petal’s construction be accurate to a millimeter. HDST and its starshade would fly nearly 125,000 miles (200,000 kilometers) apart and maintain their flight formation at a precision of a few feet (1m). Such formation flying is difficult, and slewing from one target to another would take days or even weeks as astronomers wait for the starshade to fly the thousands of miles necessary to assume a new position.

It also is an unproven technology: No starshade mission has yet flown. But such a design could see smaller, closer-in planets to greater sensitivity than an internal coronagraph and ease engineering requirements on the telescope itself. A starshade mission might fly with another Hubble-sized space telescope called WFIRST-AFTA, set to launch a decade before HDST. If so, it could be a field test for this new technology.

For now, the AURA team is setting its sights on an internal coronagraph as the higher priority. But, Seager says, “there’s no reason you can’t have both.” The final decision will rest heavily on research conducted even now, as engineers explore how and if promising technology can be delivered in time to fly by the mid-2030s.

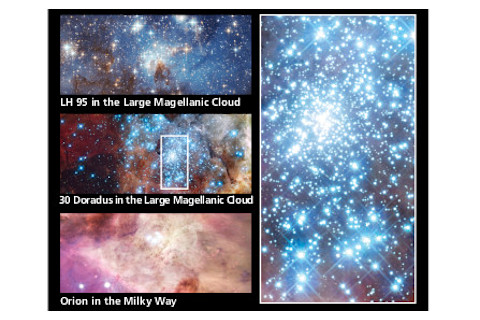

Counting individual stars outside the Milky Way is difficult but extremely valuable to astronomers seeking to understand how stellar populations are born and evolve across the universe. Currently, even stars in the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud blur together in Hubble’s eyes, while the High Definition Space Telescope will count each separate sun. (Credit: Aura)

Aura

The telescope itself, and its instruments, will not come easily. HDST will build as much as possible on current technologies either already proven on missions like JWST and Gaia, which is currently mapping a billion stars. It will call on other technologies tested and developed for missions that never flew, like the Terrestrial Planet Finder and the Space Interferometry Mission.

Engineers will catch some good breaks as well. Unlike JWST, whose infrared specialties dictated a cryogenic mission, requiring cooling at every stage of testing and assembly, HDST can be operated at room temperature. This is not an insubstantial simplification, and those infrared complications were a major contributor to JWST’s infamous cost and scheduling overruns.

Operating at lonely L2, HDST shouldn’t expect to see any servicing missions, but scientists don’t discount the possibility. Hubble’s many servicing missions taught engineers the value in modular parts: instruments and panels that can be removed, replaced, and upgraded easily. Perhaps more likely than human mechanics are robot technicians, an area NASA has been researching for a decade. A robotic servicing mission could be flown for lower cost and safety factors than a human expedition. So engineers will build HDST not expecting any such missions, but prepared if the possibility arises.

The path forward

No formal proposal is yet on anyone’s desk. No comprehensive cost analysis or timeline exists. But unless NASA chooses to forgo the space telescope business entirely, HDST will move forward.

Twenty years is a long time to wait for your next science project. Put another way, the potential to find out if alien worlds are not just habitable, but inhabited — to answer the fundamental question of whether we are alone in the universe — could be answered within most of our lifetimes. Stacked against millennia of human questioning, the project seems just around the corner.

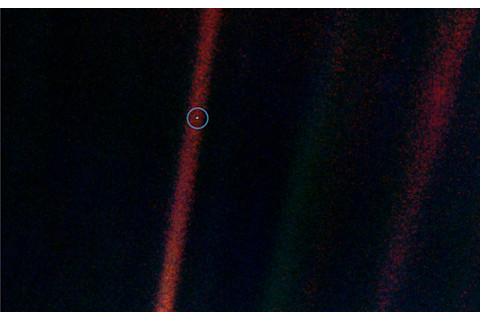

The High Definition Space Telescope represents science’s best bet to take a “pale blue dot” image of a system beyond our own. (Credit: NASA/JPL)

NASA/JPL

HDST is only one placeholder name for this project. A previous NASA study used the wistful backronym ATLAST, which has come to stand for Advanced Technology Large-Aperture Space Telescope. And once upon a time, the same basic concept was called simply the Very Large Space Telescope. In the same way, the James Webb was for many years called the Next Generation Space Telescope, and even Hubble was simply the Large Space Telescope during decades of planning.

Eventually, one assumes that the flagship of the 2030s will garner a more auspicious name, likely that of a memorable scientist or public figure. While a commissioning date is still years away and perhaps difficult to visualize past the haze of advisory panels, funding battles, and engineering victories yet to be wrought, Postman offers his choice, based on the telescope’s most fantastic goal of looking for a world that mirrors our own, and a man who made sharing that goal his life’s mission.

“You’d want it to be someone who was a true visionary in the field because it takes true vision to accomplish a project like this. I think ‘Carl Sagan’ would be a very nice tribute.”

Here’s a toast to Carl, then, and to everyone looking to further our understanding of the universe. The 2030s will be here sooner than you think.

Korey Haynes is a former Astronomy associate editor who earned her Ph.D. studying exoplanets. She’s on Twitter, @weird_worlds

[This article appeared in print as, "Meet the Next-Generation Space Telescope".]