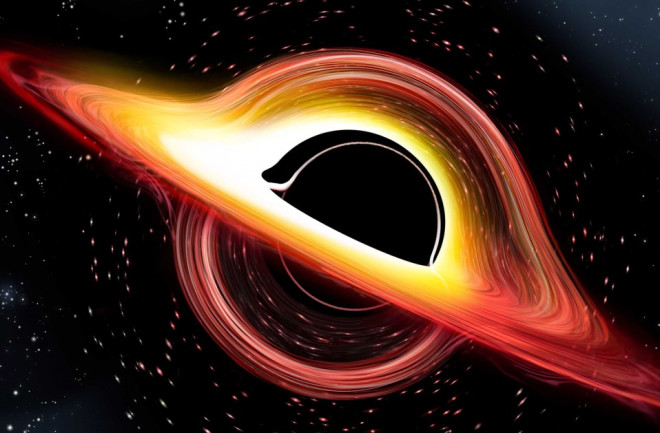

One of the most cherished science fiction scenarios is using a black hole as a portal to another dimension or time or universe. That fantasy may be closer to reality than previously imagined.

Black holes are perhaps the most mysterious objects in the universe. They are the consequence of gravity crushing a dying star without limit, leading to the formation of a true singularity — which happens when an entire star gets compressed down to a single point yielding an object with infinite density. This dense and hot singularity punches a hole in the fabric of spacetime itself, possibly opening up an opportunity for hyperspace travel. That is, a short cut through spacetime allowing for travel over cosmic scale distances in a short period.