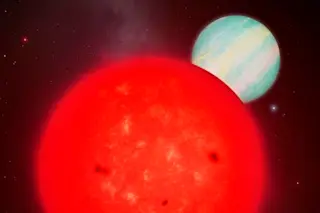

NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope may be down, but it’s not out, and its data collection is the gift that keeps giving. Scientists on Wednesday announced the discovery of 715 new exoplanets. As the largest windfall of validated planets the space agency has ever revealed at one time, it doubles the number of planets known to humanity outside our solar system. All of these planets exist within multi-planet systems similar to our own, and 95 percent are smaller than Neptune. Four are even within the habitable zone, which means they could theoretically support life-giving liquid water on their surfaces. “We’ve been able to open the bottleneck to access the mother lode and deliver to you more than 20 times the planets than had ever been announced previously,” said Jack Lissauer, planetary scientist at NASA Ames Research Center.

Kepler’s latest delivery opens up fresh territory, allowing astronomers to study both individual planets ...