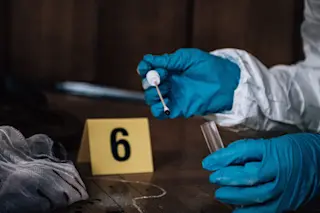

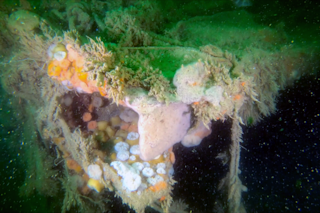

Read about more of the author’s findings in Experimental Man, published by John Wiley and Sons. When the halibut on my hook breaks the surface, writhing in a splash of seawater off the coast of Bolinas, California, I am thinking less of this fish’s fate than of my own. Considering that I plan to kill and eat it, this might seem cruel. Yet inside the fat and muscle cells of this flat, odd-looking creature is a substance as poisonous to me as it is to him: methylmercury, the most common form of mercury that builds up inside people (and fish). At the right dose and duration of exposure, mercury can impair a person’s memory, ability to learn, and behavior; it can also damage the heart and immune system. Even in small quantities, this heavy metal can cause birth defects in fetuses exposed in the womb and in breast-fed newborns whose ...

How to Tell If You're Poisoning Yourself With Fish

Researchers are creating genetic tests to determine if mercury hiding in that "healthy" dinner could be messing with your brain.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe