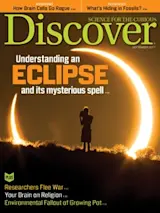

Totality's eerie light bathes the ring of massive monoliths while robed figures chant and burn their sacrificial offerings. Around them, the gathered throngs raise their voices in joy and smile for the cameras of the CBS Evening News. It is 1979, and the scene is a bizarre roadside re-creation of Stonehenge overlooking the Columbia River in western Washington state. Neo-pagans and curious onlookers have amassed to witness the rare event unfolding overhead, and this being Washington (and the 1970s), it's clear that not all the smiles and good vibrations are due solely to the solar eclipse.

Back in the studio, Walter Cronkite tells us there will not be another total solar eclipse to touch the continental United States this century. Not until the far-off date of 2017 will totality once more be so visible to so many on this continent.

I've been waiting to see this eclipse ever since.

The ...