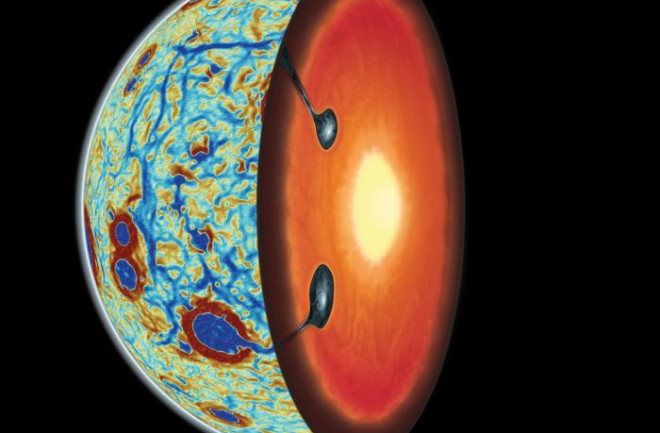

The moon’s formation has been theoretically topsy-turvy for decades. Parts of the original molten magma surface sank below the crust. Over millennia, dense minerals mixed with the mantle, melted, and returned to the surface as titanium-rich lava flows. A paper in Nature Geoscience details and confirms this transformation.

"Our moon literally turned itself inside out," said Jeff Andrews-Hanna, a University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory scientist and co-author of the study, in a press release. "But there has been little physical evidence to shed light on the exact sequence of events during this critical phase of lunar history, and there is a lot of disagreement in the details of what went down – literally."