Conceptual art for NASA's Deep Space Gateway. Its fate is up in the air due to uncertain funding and mission changes. (Credit: NASA) In my previous post I started a conversation with spaceflight entrepreneur Charles Miller, who shared his insights about how NASA's human spaceflight program got been stuck in low-Earth orbit and how we could enter a new era of deep-space adventure. Part one of the interview focused on the role of private industry in radically lowering the cost of getting back to the Moon. But it left many topics unexplored. In particular, I wanted to hear more about the economics of what some people are calling "new space": a more flexible, commercial-oriented approach to exploration. What would the economics look like? What kind of transition would liberate us from the current bureaucratic inertia? It is easy to outline a compelling vision; it's a lot harder to map out a realistic path to making it happen. Miller had a lot of provocative things to say here, too. What follows is an edited version of the second half of my interview with Charles Miller. (For more on space exploration and breaking science news, follow me on Twitter: @coreyspowell) At the end of the first half of our conversation, you were talking about space-based solar power for Earth. If we put a base on the moon, we’re going to need a good energy supply there too. How might that work? There are plenty of alternatives that could work. One is taking a small nuclear reactor [to the Moon]. Another, which we show in our report, is to pick a polar crater as your site on the Moon, where you could have solar arrays that track the Sun as it travels around the rim of the crater in a circle. I've also had many discussions with NASA and other aerospace engineers about putting a small power satellite in lunar orbit and beaming the energy down. One of my clients is DARPA, which is doing a public-private partnership to develop Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites. They recently announced that Space Systems Loral will be the commercial partner. So here’s an intriguing question: Could you assemble a small space solar power spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit [22,236 miles up] and then have it boost itself to lunar orbit to provide power to a lunar base?

The idea of a lunar fuel depot has been around for a long time; this concept is from 1984. (Credit: NASA/Marcus Lindroos) NASA has been planning a quite different kind of station orbiting the Moon, the so-called Deep Space Gateway. What do you think about it? Let me say the good stuff about it first. I think a lunar gateway is an obvious next step in an overall [lunar exploration] architecture. You need something in lunar orbit as a central transportation hub for going down to the surface of the Moon or going to Mars or going somewhere else in deep space. That said, the first weakness is it's completely uninspiring. You need to have a much broader, more compelling vision or you will lose the support of the American people. It needs to be more than just the International Space Station around the moon. The second part of my criticism of the gateway is that NASA has not conceded that this needs to be a commercial partnership, commercially owned and operated. NASA needs to get out of the building-Space-Stations mode. The ISS approach is the wrong way to do a lunar gateway; it's too expensive and takes too long. What is the right way to do a lunar gateway, then? We should do this like commercially owned and operated real estate. NASA headquarters was built by a commercial company and NASA leases the building. They didn’t design the building, and they don’t own the building. They can do the same thing in space, which would transform how we do space exploration and free up a lot of money that NASA could spend more on the exciting stuff it does rather than the boring stuff of building the Deep Space Gateway. The third issue with the gateway is that it needs to be a propellant depot. If it's going to be a transportation node, it needs to be designed from day one to where you gather the propellant for humans to go off to Mars or go anywhere else in the solar system.

Low-cost commercial approaches could finally make a lunar depot feasible. This is a new concept from ULA and Bigelow Aerospace. (Credit: Bigelow) Just to be clear: You want to see a rocket refueling station in orbit around the moon? Right! One of the key things we agree on [to make commercial space exploration work] is that we're going to build a propellant economy in space. If you build a propellant depot at the deep space gateway – a fuel station – that will drive an economic cycle in which everybody competes to be the lowest-cost provider of propellant to that station. [The current model is to mine water from the Moon or from asteroids, then split the water using solar electricity to create hydrogen and oxygen: rocket propellant.] You have all those people out there who think that asteroid mining is what we need to be doing, right? Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries and TransAstra and other companies that are being funded by the government of Luxembourg. They can go all at it and invest their money to provide propellant for the customers at this lunar depot. Then you have Jeff Bezos or Moon Express or Astrobotic, who think lunar resources are the better way to do it. There are also those who think it’s lower cost to provide propellant all the way from Earth. They can all compete. You create this economy that drives and accelerates innovation and makes space much lower-cost for everybody. I think that is a key decision that needs to be set up from day one about what we’re doing, why we’re building a lunar gateway and how we're doing it. What is the NASA role in this vision of a commercial lunar gateway? Commercial companies are going to need a customer who can lower the risk. Otherwise they're throwing money away. The biggest problem for every one of these commercial companies, from asteroid companies to lunar companies, is, who's the customer for your propellant. Where are they? Do they have any money? The natural customer for propellant at the lunar station is NASA. [A set of NASA fuel contracts] would do more than anything for lowering the risk, which would then open up private investor's pocketbooks to invest in all these companies. You have NASA set up that propellant station in lunar orbit and say, we'll buy propellant from the lowest-cost provider who can get it here safely. You'll get multiple innovative ways to go at it and NASA pays only for propellant that’s delivered. Pays only for results. If NASA moves toward a more privatized approach, what does that do to partnerships with foreign governments? We did analysis of this in our Evolvable Lunar Architecture report. Our conclusion is that you need both international partnerships and commercial partnerships. Take a look at something like CERN, which is an international partnership authority of 21 or 22 countries that includes the world's leading high energy physics experiment [the Large Hadron Collider]. That model has worked a lot better than the US-go-it-alone approach. It demonstrates how a very well-functioning international partnership could work When I was doing Evolvable Lunar Architecture, I visited CERN and met with a lot of executives there. They do not operate like a government bureaucracy. They operate much like a business. They have the authority to do commercial-style contacting. Now marry that with something like the Port Authority of New York, which practices very good safety and environmental regulatory practices while also operating great interfaces with commercial firms, and you get the best of both worlds. You get both the international aspect and the commercial aspect. So our recommendation is that we create a lunar authority that's like a mix of CERN and the Port Authority of New York. The lunar base that we’re talking about would have an international governance structure but also many of the powers of a traditional port authority, designed to encourage economic activity.

Meanwhile, what do you do with huge pieces of NASA infrastructure already underway, most notably the Space Launch System (SLS)?

I wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed in 2013 with [former Pennsylvania representative] Bob Walker. We suggested that the best path forward is to privatize SLS and let Boeing operate it on a level playing field with SpaceX and Blue Origin. I don't think anything else makes any sense. It’s an easy way for Congress to rectify the situation. In a world where the [new SpaceX] Falcon Heavy and the [upcoming Blue Origin] New Glenn rockets are launching, everybody is looking around and saying, “Why are we spending all this money on SLS?” If SLS is a better launch vehicle, it'll win on a level playing field. Boeing gets free development costs – it spent over $20 billion [in government contracts] to develop SLS. Boeing will get the benefit of that, and we'll just call that a wash. If Boeing can't compete with SLS under those circumstances then it's their problem, right? I’ve started hearing people talk about “new space” and “old space” approaches. Do you find that distinction helpful? I actually was part of the team that invented the term “new space” back in 2003, but it leads to arguments that are not useful. I think big, established companies can become part of new space by changing how they do things and by investing private capital. And I see small, relatively new companies adopting old space procedures. “New space” versus “old space” is really about how you do stuff. Are you ready and willing to take real risks, or are you looking for Uncle Sugar Daddy to take all the risk and just pay you to do the work? For example, the United Launch Alliance (ULA) has turned over a new leaf and they're investing significant private capital in their new launch vehicle. They're doing it because SpaceX has put the fear of god into them. It’s a sign that free enterprise is working. ULA’s new CEO brought in a new attitude, a new way of doing things, new policies and processes, radically lowered prices, changed how fast they operate. So I don't want to categorize some company as new space or old space. You can see a rapid turnaround.

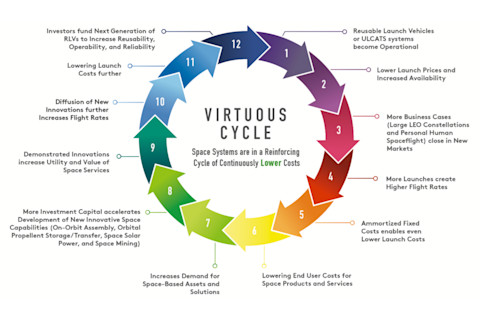

The ideal of the virtuous cycle of innovation and cost reduction, as shown in the "Fast Space" report. Earlier you mentioned your own efforts to make space access much more affordable. Can you tell me more about that? I've been working on a US Air Force study on ultra low-cost access to space. I put together a team with NexGen. We met with companies over an eight-month period about whether they're ready to partner with the US government – and by that I mean, putting in hundreds of millions to billions of dollars of private capital to accelerate the development of fully reusable launch vehicles. We looked at the markets that would need to be developed and we came up with a bunch of findings and recommendations in the analysis. You can find this online in a report published by Air University called “Fast Space.” We recommended that [ultra-low-cost access] be one of the first issues picked up by the recreated National Space Council. Beyond all the commercial, civil, and inspirational benefits, ultra low-cost would also have big national security benefits. I'm also working my next commercial space startup. You can't take the entrepreneur out of the commercial space entrepreneur. There's a little kid inside me who dedicated himself to getting humanity off this planet a long time ago.