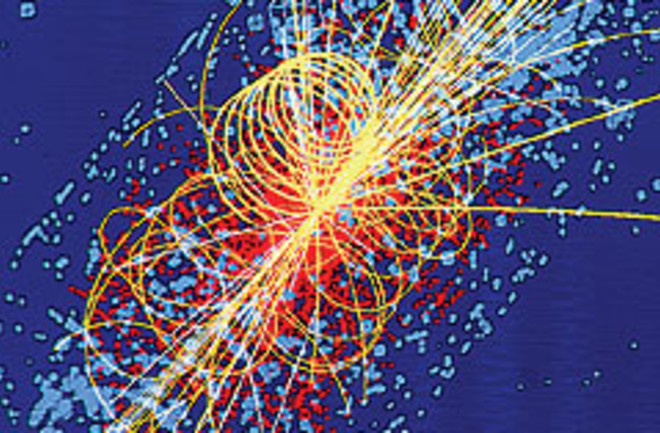

The most powerful particle accelerator in the world is the Tevatron, a ring-shaped, stainless-steel corridor four miles long that can smash together atomic fragments moving at more than 99.99 percent the speed of light. This grand device is the centerpiece of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, 45 miles west of Chicago, where scientists work around the clock to track the collisions. All of that requires a leap of faith: The Tevatron is mostly invisible, buried a couple dozen feet beneath windswept prairie.

I drove to Fermilab on a blustery winter day to learn about a subatomic phantom called the Higgs boson. The Higgs also requires a leap of faith, because so far it is entirely hypothetical. Some physicists are counting on it to help solve the most intractable riddles in their profession. It might, for instance, explain the preponderance of matter over antimatter in the cosmos. Or it might yield a formula that would unite gravity with the three other fundamental forces into a long-sought theory of everything. Above all, the Higgs could be the emissary of a ubiquitous force field that confers mass on matter. It could answer a huge question: Why does matter weigh something instead of nothing?