September 2, 1859, was a terrible day to be working in the information industry. Telegraph machines around the world behaved as if possessed. They spat out electric shocks and set telegraph paper on fire. Some of the machines continued to send and receive messages even after they were disconnected from the batteries that powered them.

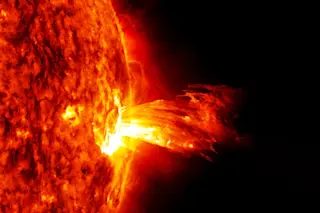

One man saw how it all began. The day before, Richard Carrington, a British brewer’s son who rose to be the foremost solar astronomer of the time, had observed an extraordinary event. He was examining an 11-inch-wide projected image of the sun, part of his routine monitoring of the solar surface, when he noted the eruption of “two patches of intensely bright and white light ... the brilliancy ... fully equal to that of direct sun-light.” Carrington knew he was witnessing an enormous explosion, nearly as bright as all the rest of the sun put together. It was the first time anyone had observed a solar flare, and the first time anyone had seen a solar event produce such tangible consequences on Earth.

Fortunately, those consequences were modest, since the telegraph pretty much defined the beginning and the end of high tech in the middle of the 19th century. If the same event happened today, the story would be drastically different. Flares and the broader solar eruptions associated with them unleash storms of charged particles, emit flashes of energetic X-rays, and temporarily mangle our planet’s magnetic field. Even for regular-strength flares, those effects can fry electronics in space and overload power transformers on the ground.

But the eruption that Carrington witnessed—now known as the Carrington Event—was hardly ordinary. It is now recognized as the most powerful solar storm ever documented. Such superflares seem to occur once every few centuries. Half-Carringtons (which are still terrifyingly potent) strike every half century or so. The most recent one happened in 1960.

A National Research Council panel recently examined the likely impact of a present-day solar superstorm. GPS signals and radio transmissions would be disrupted by the radiation blasting Earth’s upper atmosphere. Communications satellites would malfunction. Most unnerving, the electrical grid in the U.S. (and potentially much of the world) could collapse as transformers overload, leading to a wide-scale blackout that could take 10 years to repair in full. Health care, sanitation, and transportation would be crippled. The Council’s estimated price tag: up to $2 trillion during the first year alone. Or in the words of Ephraim Fischbach, a physicist at Purdue University, “The damage from a solar storm would vastly overwhelm the damage from Hurricane Sandy. Literally millions of people could die.”

The best scientists can do right now is watch the sun for signs of trouble and monitor space weather—the flow of particles and fields—between the sun and Earth. Fischbach has a better idea. He may have figured out a way to forecast the next Carrington Event far enough in advance to allow meaningful action: putting satellites in standby mode, reconfiguring critical services that rely on GPS, shutting down or decoupling key parts of the grid—things that could make the difference between short-term inconvenience and long-term disaster.

Unfortunately, Fischbach’s plan puts him squarely at odds with much of the scientific community.

A Seasonal Link?

Fischbach is the epitome of the curious soul, constantly poking around at the edges of known physics in search of something that other people overlooked: a fifth force of nature, for instance, or a flaw in Einstein’s theory of relativity. About a decade ago he noticed a juicy oddity buried in a pair of overlooked papers, one from Brookhaven National Laboratory, the other from a German measurement institute. The two teams were watching the decay of certain radioactive elements. This is a routine bookkeeping style of research: According to known physics, this type of radioactive decay is a fundamental process that unfolds at an unchanging rate, and all the researchers were aiming to do was to measure that rate and record it for reference. Instead, both teams got a rude surprise. The rate of decay in their samples was not steady but varied according to the season. That fluctuation was small, about 0.3 percent, but it was consistent and—Fischbach noted happily—very, very weird.

Most scientists dismissed the two papers as flukes and moved on. Fischbach decided to take the results at face value. “We had two experiments on two different continents seeing essentially the same thing,” he says. What effect, he wondered, could make a lump of radioactive silicon decay faster or slower?

In conjunction with his Purdue colleague Jere Jenkins, Fischbach realized that the seasonal nature of the variation might provide the crucial clue. Earth follows a slightly oval path around the sun, closest in January and farthest in July. The changes in radioactive decay rate tracked that pattern, rising and falling on cue over the course of the year. It seemed as if it affected the way atoms decayed on Earth, 93 million miles away.

Sensing they were onto something big, Fischbach and Jenkins scoured the literature and found more reports of radioactive decay enigmatically slowing down and speeding up, results so contrary to expectation that they, too, had largely been tossed into the dust bin of odd results and equipment error. Even more intriguing, these experiments also seemed to show a seasonal variation. The only way to determine if the effect was real, Fischbach decided, was to run an experiment of his own. So his group acquired a sample of radioactive manganese-54, which decays in just under a year, neither too slow nor too fast to study. Then they monitored the lump closely, and waited.

On December 12, 2006, the vigil paid off. That day, satellites in orbit around the Earth recorded a flare on the sun, which produced a spike of X-ray emissions. Also that day, Fischbach recalls, “when we looked at our data there was a sharp drop in the count rate [the rate of radioactive decay], exactly coincident with the flare.” Now he had an important additional piece of information: Proximity to the sun seemed to influence radioactivity, and violent activity on the sun could also increase or decrease decay rates.

The timing of the event presented Fischbach with more surprises. The flare happened at 9:37 p.m., when the Purdue lab was deep in darkness. If the sun was influencing the sample, it couldn’t be through light, X-rays, or any kind of ordinary particle; none of those could affect the lab at nighttime. The effect therefore had to come from something that could shine right through Earth, even at night. When Fischbach and Jenkins looked back through their data, they noticed something else extraordinary. The decay rate of their sample actually started to drop 40 hours before the flare.

Suddenly the radioactivity experiment was more than a scientific mystery. It was a discovery of immense practical significance: If Fischbach were correct, he speculated, he might have found a way to monitor solar storms day or night, and predict a violent solar outburst a day-and-a-half before it became visible. He could have a powerful, new early warning system. A sharp drop in the radioactive decay rate could alert the world to another Carrington Event. Technicians could put satellites on standby mode. Utilities could shut down power lines or disconnect parts of the grid to protect them. A serious technology breakdown could be reduced to a manageable crisis.

All that would be possible—if Fischbach were correct. Because for all of Fischbach’s confidence, many of his colleagues were convinced he was just reading a lot of meaning into a bunch of experimental errors.

The Ultimate Security Threat

The reason for this skepticism is that Fischbach’s link between solar activity and radioactive decay runs squarely against textbook physics.

The only known objects that could stream from the sun and pass right through the planet are subatomic particles known as neutrinos. But just as neutrinos can fly freely through our planet, they should also fly freely through any radioactive samples, leaving nary a trace. No known process can explain how they could mess around with radioactive decay rates. Fischbach has an idea about how neutrinos might alter the energy levels in atoms and monkey around with the way they decay even without being absorbed—a decidedly unconventional view. For now, though, he argues that theory is not the main issue. “I don’t know what the answer is,” he says cheerfully, “so let’s focus on what the phenomena are and worry about it afterward.”

What he really needs to do, Fischbach acknowledges, is overwhelm the skeptics with data. So he wants to run his experiment on a much larger scale and prove that he can reliably and repeatedly predict solar storms before they occur. He envisions a global array of about 100 manganese-54 experiments, along with tests featuring other radioactive isotopes that might work even better. Then he could monitor them against solar activity and see if, yes, he really could anticipate the next Carrington Event a day or two before it happens. He is even trying to file a patent in anticipation of the day when he can build a practical early warning system.

Fischbach frames his pitch in national security terms, since a solar superstorm certainly would be one of the worst natural disasters ever to hit this country. “Homeland Security spends nearly $60 billion a year on the usual stuff,” he says. “If we had a single sum of about $10 million, we could set up our experiment in a year and have it running full time. That’s what we’re fighting for at this point.”