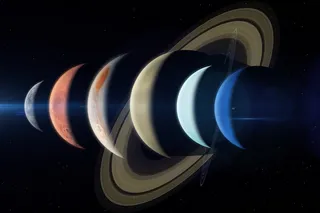

An Inside Look at Cassini's Best Images

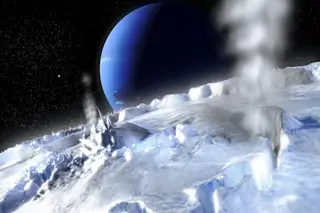

Explore Titan Beyond Rings, home to Liquid Lakes and perhaps the next Earth-like World in our solar system.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe