Tunicates, strange tube-like creatures in various colors, shapes and sizes, are found on ship hulls, larger seashells, pier pilings, seafloors and the backs of enormous crabs in oceans worldwide. Their basic shape is a short, barrel-like sack with two siphons or openings that filter feed water from one siphon for plankton before shooting it back through the other. About 3,000 species of tunicates worldwide reside in saltwater habitats. Despite this, there were no solid records of them in rock deposits for their entire evolutionary history — until now.

Paleontologists uncovered an ancient ancestor to modern-day tunicates for the first time in a recent study published in Nature Communications. The 500-million-year-old fossil is the first of its kind and is exceptionally preserved. Dubbed, Megasiphon thylakos, the specimen, about the size of a thumbprint, sports two siphons and strikingly resembles modern-day ascidiaceans, a tunicate lineage.

“Megasiphon’s morphology suggests to us that the ancestral lifestyle of tunicates involved a non-moving adult that filter fed with its large siphons,” says Karma Nanglu, study author and paleobiologist at Harvard University, in a statement. “It’s so rare to find not just a tunicate fossil, but one that provides a unique and unparalleled view into the early evolutionary origins of this enigmatic group.”

Although the animals are invertebrates, they fall under the phylum Chordata, which includes animals with backbones — making them the closest relatives to vertebrates compared to other invertebrates. For this reason, researchers are interested in studying them in the hopes that it may reveal more about the evolutionary origins of humans.

An Ancient Seafloor

In the large expanses of Utah’s desert, fossilized evidence of an ancient seabed continuously fascinates evolutionary biologists. In the Marjum Formation in Utah’s House Range, paleontologists have uncovered early life like trilobites, algae and sponges. Each fossil gives scientists windows into the Earth’s Cambrian past. And it's where the first Megasiphon thylakos fossil was found.

“The fossil immediately caught our attention,” says Javier Ortega-Hernández, study author and invertebrate paleobiologist at Harvard University, in a statement. “Although we mostly work on Cambrian arthropods, such as trilobites and their soft-bodied relatives, the close morphological similarity of Megasiphon with modern tunicates was simply too striking to overlook, and we immediately knew that the fossil would have an interesting story to tell.”

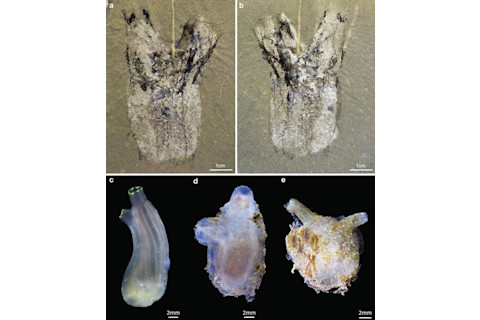

(Credit: Rudy Lerosey-Aubril (a,b) and Karma Nanglu (c,d,e))

Rudy Lerosey-Aubril (a,b

Nanglu says that the preservation of the early tunicate fossil is a miracle. Tunicates are mostly soft-bodied, and well-preserved fossils tend to be more bony. For this reason, tunicates were almost completely absent from the fossil record.

“There's essentially nothing for this group [tunicates] that's very ecologically successful in modern oceans. We have very little of direct evidence of what they used to look like in Earth’s distant past, so the fact that there's one specimen of this one group of animals that's very successful today is a huge surprise in and of itself,” says Nanglu.

Ties to Modern Tunicates

Other tunicate fossils were uncovered in the early 2000s near Kunming, China. But Nanglu argues that this one is the most well-preserved. “This fossil is the only one that shows the soft body and anatomy of this animal. The whole body, from its base all the way up to the siphons, is complete. If you throw it up next to an image of a modern tunicate, you can make many one-to-one comparisons,” Nanglu says.

There are two major lineages of tunicate called ascidiaceans and appendicularias. Ascidiaceans are also known as ‘sea squirts’ because they shoot water through the siphons when startled by sudden movement or touch. Most sea squirts start their lives with similar appearances to tadpoles and can move around. When they morph into a vase-shaped adult with two siphons, they remain attached to one area for their entire lives. Appendicularians, on the other hand, are free-swimming animals.

Before this find, researchers relied on what could be learned from modern tunicates to understand their past. And since no firm evidence existed before about the morphology and ecology of the last common ancestor of tunicates, it was hypothesized that tunicates were either ascidiaceans or appendicularians.

A Familiar Shape

The ancient fossil has the markings of an ancient ascidiacean tunicate. With its vase-shaped body, two prominent siphons and dark bands running up and down the fossil's body. Compared to a modern tunicate, Ciona intestinalis, the team found that the bars along the body of the ancient fossil were similar to muscles C. intestinalis uses to open and close its siphons. Suggesting that the 500-million-year-old fossil, at one point, was fixed to a surface and filter-fed in the ancient ocean.

Nanglu explains that fossils as small as M. thylakos often are neglected when experts are out in the field collecting fossils for analysis. “At first glance, this thing [the tunicate fossil] may not look nearly as interesting. Still, they are super important and often have an interesting evolutionary story to tell once you delve into them.”

With this find, the team found evidence that the body plan of modern tunicates was established not long after the Cambrian explosion. “We'd love to find more for sure,” says Nanglu.

Read More: Palm-Sized Sea Creature Named the World's Oldest Animal