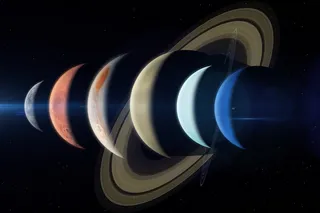

By age 6 Emily Schaller had two obsessions: figure skating and the planets. By 9 she was a competitive skater, attending summer training programs and eventually becoming an early member of the Dartmouth College team, in 1998. Today Schaller uses in-line skates to get around Tucson, where she is a Hubble Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Arizona. Her fascination with the planets has proved even more durable: Schaller now uses NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility(IRTF) on Mauna Kea in Hawaii to monitor methane clouds on Titan, where bizarre weather patterns could explain the extraordinary lakes, streams, and channels observed on Saturn’s largest moon.

When did you know you wanted to study outer space? When I was 5, my mother got me a picture book of the solar system. The pictures of each planet were just drawings, but I kept looking at the images thinking I saw important things. In college an internship at NASA really cemented my feeling that I wanted to get a Ph.D. in planetary science.

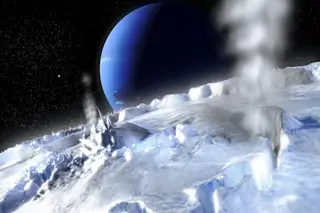

What drew you to Titan? If you didn’t know you were looking at the surface of Titan, you might think you were looking at Earth because there are river valleys, channels, and lakes that seem very familiar. Titan is the only moon in the solar system with a substantial atmosphere and the only place besides Earth with a weather cycle we can study. But Titan’s surface temperature is about –290 degrees Fahrenheit, so cold that methane condenses to liquid form. Instead of water, Titan’s clouds and rain are made of methane. A year there is about 30 years on Earth, so we haven’t even studied one full Titan weather cycle yet.

What does your research focus on? I want to know where Titan’s clouds are located and how that relates to its surface features. IRTF data allow me to probe down to different levels in Titan’s atmosphere to measure the amount of cloud coverage. Earth is about 60 percent covered by clouds. On Titan, usually there’s less than 1 percent coverage, but it can go up to 10 percent, as happened in 2008. We’re trying to understand what the outbursts of activity mean. The clouds might be related to a geyser spewing methane from the interior or icy volcanoes heating the surface.

Why should we care about weather on Titan? A lot of the chemistry there may be analogous to processes that occurred when Earth was young.

Any surprises in your research? Nearly every night for three years, I used IRTF to monitor the weather on Titan, but there were very few clouds. Then the morning I handed in my Ph.D. dissertation in 2008, I saw those huge clouds forming. As soon as I turned it in, the clouds decided to throw a party.