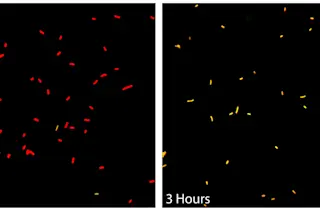

Forensic science, often used to produce evidence for criminal trials using such techniques as fingerprint analysis, is "badly fragmented" and unreliable in the U.S., according to a report by the National Academy of Sciences. Crime laboratories around the country are grossly underfunded, lack a scientific foundation and are compromised by critical delays in analyzing physical evidence…. The report calls into question the scientific merit of virtually every commonly used forensic method, including analysis of fingerprints, hair, fibers, blood spatters, [and] ballistics [The New York Times]. According to the report "no forensic method"—with the notable exception of DNA analysis—"has been rigorously shown able to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source." Of particular concern is the use of comparative forensic methods like hair or fingerprint analysis to match a piece of evidence to a particular person, weapon, or place ...

Verdict on Forensic Science: It's Quite Bad

Explore forensic science reliability and the questionable methods behind fingerprint analysis and DNA accuracy in criminal trials.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe