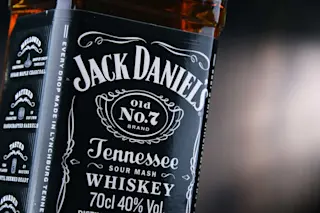

Jack Daniel's Tennessee whiskey is one of many made using the famed Lincoln County Process, which takes its name from the area where Jack Daniel's was first made. (Credit: monticello/shutterstock) Champagne is only champagne if it’s made in its namesake region in France, Scotch is exclusively distilled and matured in Scotland, and a “bourbon” label is reserved for products from the United States. And there’s one variation on the bourbon recipe — Tennessee Whiskey — that’s made exclusively in, well, Tennessee. You might be familiar with its largest maker, Jack Daniels. But Tennessee whiskey isn’t just bourbon distilled across a state line. (95 percent of bourbon comes from neighboring Kentucky.) To make it, distillers put their whiskey through an extra step, called the Lincoln County Process, named for the location of the original Jack Daniel’s distillery. This process “charcoal mellows” the whiskey, filtering the spirit through charred wood, usually sugar ...

Science Uncovers the Secrets of Tennessee Whiskey

Explore the Lincoln County Process in Tennessee whiskey, a unique step that mellows and refines the spirit's flavors through charcoal.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe