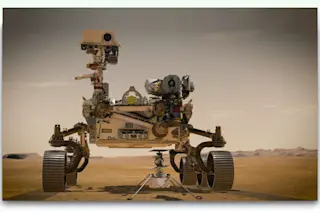

According to the vision of Klaus Lackner and Christopher Wendt, a few short decades from now the desert chaparral of what was once the White Sands Missile Range in southern New Mexico will be transformed into a strange new world. For hundreds of miles in every direction the alkali flats will be covered with a blinking array of solar panels. These might look familiar enough, but not the little suitcase-size robots scurrying among the panels on a grid of white ceramic tracks.

The robots, called auxons (from the Greek auxein, to grow), are designed for specialized tasks. Digger auxons scrape an inch of dirt off the desert floor. Transport auxons carry the dirt to a beehive of electrified ovens. Out of these ovens, which work at superhigh temperatures, come useful metals, like iron and aluminum, or the silicon required for making computer chips. Production auxons shape these materials into machine ...