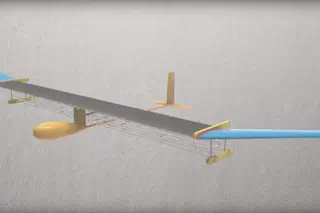

Bonny Doon is hardly the place one thinks of visiting for high-tech thrills. Once an old logging camp, the tiny hamlet northwest of Santa Cruz, California, sits at the end of a country road, past miles of empty beaches and strawberry farms. Hang a left before you reach the vineyard and you find a short dirt track leading to a barn. And then, amid hundreds of acres of redwoods out back, you encounter an avatar of the future—a whirring black gizmo, about the size of a bread box, zipping around overhead. The strange flying object is controlled remotely by a cluster of giggling engineers. Their leader, a tall man with the build of a gazelle, windswept blond hair, and a permanent grin, starts extolling the possibilities of his device before he remembers to introduce himself.

To inventor JoeBen Bevirt, the flying black box holds our clean-energy future, a world in ...