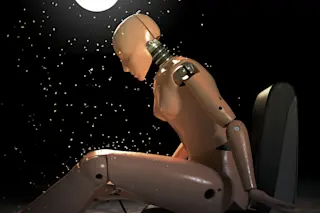

Horror stories abound about patients given general anesthesia who claim they were in fact awake during surgery---and of course it's everyone's worst nightmare. Brain states are routinely monitored during surgery for this very purpose, but new research finds that a more precise method of analyzing brain waves could better detect when people are and aren't conscious under anesthesia. A group of researchers from MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital administered propofol (the most widely used anesthetic drug) to healthy volunteers. The researchers attached electrodes to participants' scalps and hooked them up to an electroencephalogram (EEG) machine. This set-up recorded the patterns of electrical activity tied to brain function as the participants experienced the stages of general anesthesia: unconsciousness, amnesia, analgesia, and immobility with physiological stability.

Researchers measured patients' responsiveness to audible cues like mechanical clicks and spoken words. The volunteers pushed a button every time they heard a sound. Researchers also analyzed patients' spontaneous brain activity via EEG. They found distinct patterns between volunteers' conscious and unconscious states which can be used to trace a patient's position on the general anesthesia spectrum. When patients were first starting to lose consciousness, the peaks from their alpha brain waves (those that usually occur when a person is relaxed with eyes closed) aligned with the bottoming out of their lower frequency brain waves. When actual unconsciousness hit, the alpha waves flipped, so the peaks of the alpha and lower frequency waves occurred at the same time. The researchers think this shift disrupts normal communication between regions of the brain, resulting in unconsciousness. They published their results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday. Most patients are already hooked up to EEG monitors during surgery, but the machine usually compiles the data and spits out a single reference number. By instead looking for the specific brain patterns associated with the phases of anesthesia, doctors can now put the EEG output to better use, the researchers say, and ensure that patients aren't coming out of general anesthesia too soon. Image courtesy of Joseph A. Boomhower/Flickr