Everybody loves the idea of photovoltaic solar cells: endless clean electricity generated directly from sunlight. The problem lies in the messy reality of making the technology work well. For instance, says Boston College physicist Michael J. Naughton, the cells’ two functions—capturing light and making energy—pull the optimum design for a solar panel in opposite directions. “‘Photo’ wants it thick,” Naughton says, “but ‘voltaic’ wants it thin.” So Naughton and other like-minded scientists are rethinking the fundamental elements of solar cells. They aim to rewrite the rule book and finally make solar energy cost-competitive with coal and natural gas.

The limitations of current-generation solar cells are painfully clear. Although experimental cells have reached efficiencies greater than 40 percent, most silicon-based commercial designs struggle to get past about 20 percent. The lower the efficiency, the more cells it takes to generate a given amount of electricity. That in turn makes photovoltaics bulky and expensive. As a result, the United States had just 800 megawatts of grid-connected solar photovoltaic power in 2008, and solar accounted for less than a tenth of one percent of all energy consumed in the country.

Naughton is trying to boost efficiency by tackling the thick-thin dilemma. The thicker a solar cell, he explains, the more light it can capture. But when it comes to generating electricity, thin is best: Electrons must travel farther in a thick cell, so fewer reach the photovoltaic layer where they create usable electricity. Naughton’s approach is to add an array of extremely fine wires that stand up vertically on the flat plane of a solar cell, like a miniature bed of nails, to catch additional rays. Although they are just a few microns tall, the wires—made of a metal, often silver, and coated in a thin layer of photovoltaic amorphous silicon—can substantially boost efficiency. Solar cells with this construction could soak up about 10 percent more light without requiring a thicker panel. Groups at Caltech and at the University of California at Berkeley are working on similar kinds of wire-enhanced cells.

Another roadblock hindering solar cells is that much of the light they collect is wasted as heat and not converted to electricity. When sunshine strikes a solar cell, some of the electrons in the cell take on energy but quickly lose most of it as thermal energy rather than breaking loose to become part of an electric current. Naughton and colleagues are at work making improvements here, too. They are trying to tap these so-called hot electrons before their energy dissipates. They hope that a layer of small semiconductor crystals called quantum dots may be able to extract the high-energy electrons before they cool, potentially doubling solar cell efficiency. Naughton’s group has already successfully extracted hot electrons in a superthin silicon flat panel and next plans to combine that approach with the wire array architecture.

Physicist David Carroll of Wake Forest University takes a different approach to the challenge of capturing more sun. Existing flat panels, he notes, work best only under direct sunlight; the low-angle rays of the early-morning and late-afternoon sun are mostly reflected away and lost. So Carroll and his team are developing solar cells that can grab light from many angles throughout the day. Their creation, called the FiberCell, is constructed from bundles of glass-cored fibers sprayed with an inexpensive proprietary polymer that captures photons even from oblique angles and converts them into electricity. Many bundles can be joined together to create a flexible mesh, and the device “basically doesn’t care about the angle at which light strikes,” Carroll says.

Such solar cells could be ideal for home rooftops, where the sun usually hits at odd angles, Carroll argues. And rather than relying on expensive photovoltaic materials like copper indium gallium selenide, FiberCell could work well with much cheaper polymer-based cells. Carroll says that his system can double the efficiency of conventional panels, and he will soon send out a sample FiberCell for independent performance testing.

The thick-thin paradox and indirect sunlight are not the only limitations holding back photovoltaic cells. Berkeley physicist Jan Seidel is tackling another, the so-called band gap problem. In this case, the stumbling block is that the semiconductor materials in solar cells, such as silicon, become conductive and generate energy only in response to photons at certain energy levels. Since the electrons in these semiconductors cannot generate more energy than they initially absorb, cells are limited in how much voltage they can produce. Seidel and his colleagues recently found that an inexpensive material called bismuth ferrite can produce high voltages that break through the band gap limit. He has not yet incorporated the material into a working solar cell, but his initial experimental results look promising. Some hurdles remain before bismuth ferrite will be ready for prime time, though: Power—the rate of energy output—relies not only on voltage but also on current. So far, the amount of current that Seidel can coax from bismuth ferrite remains too small for practical applications, but he and his colleagues are working to improve it.

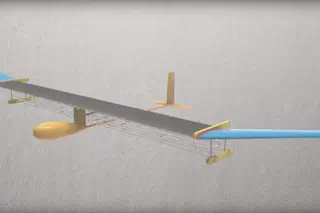

Some proponents of solar power think the ultimate solution lies in a radical change of direction—literally getting photovoltaics off the ground. In space, where there is no shade or night or cloud cover, solar installations could provide nonstop power at the best possible efficiency. The challenges here dwarf those of ground-based solar power: Getting huge solar panels into orbit could be technically difficult and costly, and engineers will need to devise a safe, efficient way to beam the energy back to a receiving station on Earth. But the potential payoff is also enormous, and Japan’s space agency, JAXA, has announced a $21 billion plan to get giant commercial solar panels with an area of more than a square mile into space by the 2030s. The agency aims to launch a smaller, experimental solar satellite within the next decade.

Private companies are gearing up to grab solar in space as well. In December, the state of California approved a deal in which utility giant Pacific Gas and Electric would purchase 200 megawatts of power from a space-based system that will be deployed by Solaren Corporation by 2016.

BuzzWords

Amorphous Lacking a regular internal arrangement of atoms. (In contrast, a crystalline solid has a repeating pattern of internal atomic structure.)

Hot Electron An electron in a solar cell bearing more energy than can typically be extracted as electricity.

Quantum Dot A cluster of atoms so small that its electronic properties are governed by the laws of quantum physics.

Band Gap The energy threshold required to excite an electron in a semiconductor, allowing it to carry electrical energy.