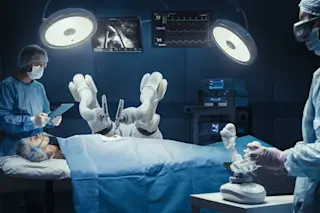

Hacking Medical Technology With Legos and Sequins

At MIT's Little Devices Lab, tinkerers are envisioning the future of medical tech in the developing world.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe