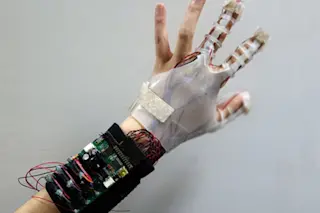

Amid acres of gently waving corn, just north of Missouri's Ozark Mountains, neuroscientist John Kauer strides through a grassy field studded with land mines. He swings a foot-long brushed-aluminum box by its black handle, sweeping it back and forth over the ground. There is no sound save the rustling of the cornstalks. Then the box abruptly bellows "Land mine!" in a voice recorded by a former drama student working in Kauer's lab at Tufts University in Boston.

The defused mines at this 22-acre government test site are used to help Kauer find a better way to locate the roughly 110 million live ones buried in Afghanistan, Bosnia, Cambodia, and other past and present combat zones. "Because they are so difficult to find, people are losing limbs and lives, and countries with economies based on farming can't rebuild after war," he says. In most of the world, land-mine clearing is a ...